Reviving San Cassiano – Paul Atkin Discusses his Plan to Rebuild the World’s First Public Opera House (Part 1)

By Alan NeilsonThe year 1637 saw one of operatic history’s defining moments: Venice’s San Cassiano theatre, the world’s first public opera house, opened its doors to the paying public for the first time for a performance of “L’Andromeda” by Francesco Manelli to a text by Benedetto Ferrari. Anyone who could afford the price of a ticket could attend. Opera had escaped the confines of the palazzi and the nobility and became a public entertainment; although by no means a cheap one!

Such was its success that other theatres quickly followed suit and converted to opera houses. The city became a centre for the new public art form, attracting the best singers, musicians and composers from the Italian peninsular. Tourists flocked from all over Europe to see the musical spectacle with its fabulous special effects.

Over its lifetime, the San Cassiano premiered many notable operas, including Francesco Cavalli’s “Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo“ (1639), “Gli amori d’Apollo e di Dafne“ (1640), La Didone (1641), “La virtù de’ strali D’Amore” (1642), “L’Egisto” (1643), “L’Ormindo” (1644), “La Doriclea” e il Titone” (1645), “L’Orimonte” (1660), “Antioco” (1658) and “Elena” (1659).

Over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries it underwent a number of structural changes and refurbishments, but by 1776 decline had truly set in. So far had it fallen that Giacomo Casanova was able to report that the San Cassiano theatre had become a place where “women of the underworld and prostitutes… can be found committing crimes.” The last operas to be performed there were probably Pietro Guglielme’s “La sposa di stravagante temperamento” and Sebastiano Nasolini’s “Gli umori contrari” during the 1798 season, before the doors of the theatre were closed for good in 1805.

Yet, the legacy of the San Cassiano lives on, as opera houses around the world present a public entertainment that has so far lasted nearly 400 years, providing some of the world’s greatest music and artistic achievements. And, despite its ability to enrage and provoke controversy with claims of elitism and overly generous public subsidies, opera is still with us.

Unfortunately, the San Cassiano is not. As with Venice’s other 17th century opera houses, which have either been destroyed or converted beyond all recognition, the San Cassiano has disappeared, demolished in 1812 to make way for a garden: a piece of opera’s history now lost forever.

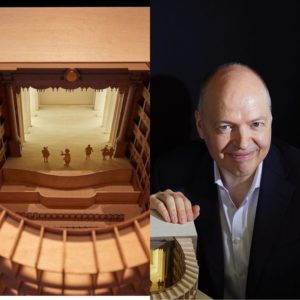

Enter Paul Atkin

At least, that was the position until Paul Atkin stepped onto the scene with a mission to rebuild the San Cassiano theatre to its original 1637 design, including its original stage machinery, and present baroque opera in what would be the only fully functioning 17th century baroque theatre in the world.

OperaWire met with Atkin to discuss his ambitious plan in what turned out to be an extended and wide-ranging interview, covering not just the basic outline and aims of the project, but a detailed, in-depth consideration of all aspects relating to the theatre’s construction, financing, performance possibilities and its role as a public opera house.

Any sense that this might simply be another opera enthusiast’s pipe dream were quickly dispelled by his practical approach, down-to-earth manner, deep knowledge of theatre and baroque opera, along with his astonishing level of commitment. In this first of a three-part interview series, Atkin talks about his background, motivations, and vision for rebuilding the San Cassiano.

So who exactly is Paul Atkin? He is a man who certainly loves music and has a passion for opera, as illustrated by his reaction to a performance of “L’Orfeo” at the Barbican which he was not happy with.

“I hated it so much that I wrote a letter to my wife who was away at the time. I spent five hours telling her about how bad it was. I had punk music blasting down my headphones, I was so angry,” he told OperaWire. He then calmly reflected that, “Probably, if I went back now, I would enjoy it.”

And if you assumed that someone committed to rebuilding the San Cassiano must be solely focused on the baroque and traditional, you would be wrong.

“I am by no means a purist. I also love modern opera; I love all opera. I take the view that when I go to an opera it is for them to do what they feel is right and to push the boundaries and experiment. Obviously, it can fail, but it can also work. There are times I have walked out of the theatre furious, and on other times I have loved it. You have to have both.”

Atkin was born in East Anglia in England, into what he describes as a poor family and by his own admission was not very good at school.

“I wasn’t that bright and left school at 15 with only three O-levels.”

Clearly, he had not yet found his calling. Atkin went on to become a successful businessman and to complete a doctorate in musicology under Tim Carter.

Rebuilding San Cassiano

His idea to rebuild the San Cassiano did not come as a sudden revelation, rather it developed slowly over time, the first seed being planted during a trip to theatre.

“I saw a production of “Julius Caesar” at the Globe Theatre, in what was an historically informed performance, and everything about the play became so clear. I understood what Shakespeare was actually writing about. It is a fantastic arena, and I realized that the historically rebuilt theatre itself was an important factor in revealing certain meanings within Shakespeare’s play. What they do and have achieved at the Globe is phenomenal.”

The idea crystallized in 1997 when he was studying in Italy.

“I remember thinking that the San Cassiano was the first public opera theatre in the world and now nothing remains. There is not a single functioning 17th century baroque opera house in the world, and that is not right. Someone has to rebuild it, so I thought: lets do it.”

It is, of course, easy to make such a grandiose declaration, but it is a completely different thing to bring it about, something Atkin was very aware of, especially as he had two major obstacles to overcome.

“Firstly, I didn’t feel qualified to talk about opera because I hadn’t finished my doctorate in opera production, so I needed to finish that and to become more of an expert on theatres; they are special and I needed to understand them. Secondly, I didn’t have the money, so I thought I had better go and earn some. So I set up a business, finished my PhD, started a family and in 2014 I sold my business interests which gave me the funding to start this project.”

Atkin is eager to point out that this is not a gimmick, it will not be a faux theatrical experience to entertain passing tourists, but a serious academic and musical enterprise.

“I happen to believe that when you perform an 17th century opera in a modern setting you lose half the meaning of the piece, you get contradictions that just don’t work. I want to try to get to the core truth of the piece, and that can only be a good thing. If seeking this core truth in a work is not your thing then there are plenty of other theatres you can go to. The San Cassiano will be unique in being able to explore this idea.”

“I recovered Giannettini’s opera “L’Ingresso alla gioventù di Claudio Nerone” when I was doing my PhD. At that point I was probably the world expert on this opera. We managed to get it staged at Český Krumlov in 2018. Within a short time the maestro, Ondřej Macek, knew far more about the opera than I did, far more. Just by staging it, it is possible to learn so much, such as the way singers need to be positioned. Just reading it does not work. I now know I got things wrong in my research. The meaning of the words change according to the direction a singer is facing, whether they are addressing the audience or another singer. It is only by staging it that we can discover certain things, and by staging it in a 17th century theatre—in other words, a theatre for which the operas were written—we will learn even more. We just don’t know what we don’t know. It can’t be right that we don’t have the right type of theatre to stage 17th century baroque opera, and without one it isn’t possible to fully develop our understanding of it. We have to fix that and that is what this project is about. It is going to be very exciting!”

So what can we expect to see on stage? Will an attempt be made to recreate everything as it was in 1637, at least to the extent we understand it? On this Atkin is adamant: “Absolutely yes! We must remember this was the place where the most exciting events in the world of theatre were happening, it was the Hollywood of its day, it was about special effects. Our research has shown that they actually used real fire onstage, it was not fake. They also used real fountains onstage, with water. The operas had spectacular visual endings for which they used the leading technology of the day. We want to pursue this.”

The idea of watching a 17th century opera in its original conditions, with its fabulous special effects is, indeed, very exciting, but it will surely be a huge logistical and costly project, which will encounter many obstacles and setbacks along the way, and no doubt be off-putting to many investors and entrepreneurs. Yet, Atkin appears unfazed by such concerns.

“We originally called this ‘the impossible project,’ and took the view that if we came out of every meeting and we were still alive, that we hadn’t been killed off in that moment, then it was a success. And we have managed to progress; what was once impossible became very difficult, then became difficult, and now has become feasible. We are very close to the position were everything is in place and ready to go.”

Two Major Challenges

Apart from the obvious difficulties in trying to reconstruct the theatre itself, two other problems immediately spring to mind.

Firstly, there is the Italian bureaucracy, known for its byzantine complexity and inflexibility. Atkin’s time spent living in Italy has provided him with a valuable understanding of it and enabled him to take a multi-pronged approach with it. The first thing he did was to adopt the Italian style of doing business.

“I had to drop my London business style on day one. I want things done immediately, and if they are not I want to know why. That is not the Venetian way. Just because a certain party has not got back to me for three weeks does not bother me; they have their reasons and I know they will. If it were London I would be on the phone everyday wanting to know what was happening. This has probably been the most important thing we have done.”

He also realizes the importance of getting the political parties on board.

“We have taken a bi-partisan approach from the beginning. We have the support of the mayor, he has been very good, very kind and he has given us his backing, but we are also talking to the other parties because we want this to go through as a bi-partisan project.”

He is also aware of the importance of having the people of Venice closely involved in the project. After all, it is going to be a public theatre, and, therefore, he is determined to put Venice first.

“We are not imposing our ideas on Venice, we want Venetians involved. We have employed about 26 Venetian companies since we started, and we will also employ about 160 Venetians when we are fully operational. We try to consult and share everything we are doing with the people. I want the Venetians to feel that it is their theatre. It is important that when the San Cassiano is open they can walk in there during the day, free of charge and if they want to have a coffee in the bar or step into the theatre and watch rehearsals they can. We want it to be open, as this is part of how we envisage a public opera today. It is important that the word ‘public’ is more than just marketing or a catchphrase.”

Secondly, there is the matter of finance. Up to this point, Atkin has financed everything out of his own pocket and has so far spent £3 million. He has talked to many potential investors and has received many encouraging responses, but as yet no money. He is not, however, pessimistic. He is quite the opposite.

“At the moment we are trying to raise €20 million to secure our site to start building. So we are still in the period of risk. The key is to start building: when people people see that it is happening, then they invest.”

He is completely honest about the situation.

“I am a no-one. If I was Prince Charles or Philippe Jaroussoky, a ‘Name,’ I would be able to sell myself a lot more easily. I cannot personally put in €20 million; otherwise I would. It is a chicken and egg situation at the moment, I need the money to start building, but investment will only come when we start building. However, once we get the green light from the Venetian authorities, we will see movement.”

It is an optimistic assessment from Atkin, but given his track record in business, why should he be doubtful? As he says, “I can write business plans and cost investment projects, it is my background. I know this project will make a return for investors.”

Moreover, this is not about glory or building his own personal legacy: it is about rebuilding the San Cassiano. “If someone reading this article thinks this is something they can be involved in, then they can have their name written into opera’s history. I can’t do this alone!” Atkin expects to start building very soon: “If we start building today, the theatre will open its doors in 2024.”

In the second part of the interview, Atkin discusses the designs for the San Cassiano and performance plans.