Casta a Diva – Lydnsy Spence on the Challenges of Digging into the True Story of Maria Callas the Woman

By David SalazarLook at most books about opera legend Maria Callas and you’ll recognize some iconic representation of the famed diva.

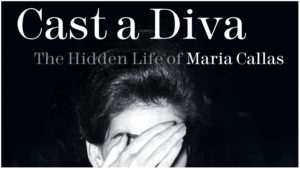

But glance at the cover for “Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas” by Lyndsy Spence and you’ll find something else. Instead of seeing the soprano look back at the reader, what we get is a black and white image of Callas covering her face with her hand, her features completely obscured from view. She’s not looking at us but intentionally hiding from view.

For a star who embodied some of opera’s greatest roles with a ferocity and penchant for intense and immersive drama, this strikingly subversive image immediately pulls you in.

And like this against-the-grain image, the book also aims to set certain records straight about Maria Callas (born Sophia Cecilia Kalogeropoulos) the woman. What follows is a stunning and harrowing book that portrays a woman fighting for her rights and her life every step of the way.

“I wanted to portray her as a human being as opposed to this myth, this diva,” Spence told OperaWire in a recent interview about the book, which was released in September.

Callas had been on Spence’s radar for years. She was always into classic cultural icons, and the Greek soprano was at the forefront of her childhood obsessions.

“I loved her since I was a teenager. I have been doing the Callas eyeliner since I was 14,” Spence noted.

Spence read everything she could get her hands on about Callas (she singled out “Callas: The Greek Years” as the best of the bunch) and watched all the videos available on YouTube.

But as she grew older, she found that while she admired the artist, she didn’t know the person behind the stage persona.

“I always felt like I didn’t really know Maria. I knew Callas the artist, and all the trivia. I knew Onassis, but I never felt like I could connect to Maria.”

And from there emerged the desire to explore Maria, the person behind Callas the legend. She pitched the book to her editor and got the yes she needed to move forward.

That was in 2019. Spence, who previously wrote “The Grit in the Pearl: The Scandalous Life of Margaret, Duchess of Argyll” and is the founder of the online community “The Mitford Society,” noted that she is an intense researcher and the COVID-19 lockdown briefly impeded her from accessing certain essential resources at Stanford, Columbia, and the New York Public Library.

So she took that time to do other research and dwelled on some theories she had about Callas’ life, specifically the many narratives that had been propagated over the decades since the soprano dominated the opera world.

Then when the institutions opened up, she went right to the sources, questioning her theories via the many letters that the soprano had written over the years.

“Sometimes the letters don’t seem to be anything special. Sometimes they just to seem to be the daily life of Callas,” she noted. “But when you really get to know her, you can really read between the lines of what she is saying, without being too specific.”

Among the many facets of Callas’ life that Spence wanted to explore was the state of her health at the time of her death from a heart attack in 1977. Callas was 53 when she died.

“I have always felt that Callas had something wrong with her. Her health,” Spence noted. “Just looking at footage of her in Germany in the early 60s, and then footage of her when she is directing with Di Stefano in Italy at the time … just the way that she carried herself. The way she moved. And I was going through my own neurological health issues at the time and something resonated with me that Callas had something similar going on.”

In the book, she explores Callas’ addiction to Mandrax, a drug formed of methaqualone and antihistamine diphenhydramineamine, which was a “powerful sedative” that provided a “hypnotic effect” (page 255 in the book).

“One pill a day for two months alters the body’s chemistry and causes physical and psychological dependency. Withdrawal from Mandrax can cause death if done without medical assistance,” Spence writes in the book.

What Spence unearths is that Callas received a steady supply of the drug from none other than her sister Jackie, who got the drug from an Athenian chemist. Spence also notes that it is believed that Callas’ mother Litsa was involved in the drug’s acquisition.

This ties into arguably the through line of Spence’s book – Callas’ battle with abusive relationships throughout her life. From her mother, sister, and husband exploiting her talents throughout her career to Onassis abusing her mentally, physically, and emotionally, to even an ongoing battle with an audience with which she had a contentious relationship, there was seemingly no end to her struggle. The book is replete with intense depictions of the different kinds of violence that these people inflicted on Callas throughout her years. The Onassis chapters are particularly shocking.

Perhaps one of the most graphic scenes in the book comes in the epilogue (page 262), where Spence describes Vasso Devetzi (a “friend”) and Jackie going through Callas’ room and her possessions (hundreds of dresses, blouses, shoes) while “Maria’s corpse remained in the room, a silent witness to their intrusion.” Her funeral was rushed before a proper examination of her estate was realized, setting the stage for questionable distribution of her assets that would lead to disputes that stretched into the 21st century. Even in death, Callas’ image was being exploited by whoever could get their hands on it.

It was something that Spence was privy to throughout her research process.

“Look at Callas’ environments. Greece in 1940s. She doesn’t have a chance in terms of women’s rights. Italy in the 1950s. She’s her husband’s property,” Spence noted. “So if I can understand her environment, I can understand what she was up against. People who say they knew her would say that a woman like Maria Callas wouldn’t put up with something like that. She wouldn’t stand for that.”

Understanding this context and these relationships allowed her to dispel one of the many myths and legends that have always attributed to Callas as the consummate diva – her temperament.

“Technically, she wouldn’t and she couldn’t vent,” Spence noted. And this is where her frustration was coming from and the tantrums. But in terms of the law and her place as a woman in these kinds of societies, she had no rights. And it’s not just Callas. She wasn’t the only one the system abused back in the day. She was like every other woman living in this time who couldn’t get a divorce. She was pregnant from Onassis in 1960, but she didn’t stand a chance of carrying that child to term. And seeing what she was up against also made me understand how people were able to manipulate their authority over her. Her mother and her sister … her sister plays dumb.

“People who try to exploit her image today in a certain way for their own benefit, I think they use certain things to control her image to alienate and exploit her. It’s all about knowing how to play the system.”

Spence did note, however, that she had no intention of portraying Callas as a victim, “but there’s no getting away from what happened. You have to call a spade a spade. And she might have screamed at [her husband Giovanni Battista] Menenghini and thrown a tantrum, but that was her frustration. It wasn’t bad behavior.

She wasn’t this horrible bitch-like figure everyone makes her out to be,” Spence added. “Reading her documents, I actually find her to be very approachable. Her energy and her story, I found her so approachable in terms of who she was.”

In doing her research for the book, Spence reached out to many people who knew or had relationships with Callas. And this is where she found some of her most complex interactions.

“Everyone is so forthcoming when they think that you’re going to celebrate Callas,” she noted. “But when they know that you’re going into the ins and outs of things, they get pretty dodgy.”

One such person was Giovanna Lomazzi, who met Callas in 1952 when she was 20. Per Lomazzi, Callas called her “little sister.”

“She went on and on about how she was Callas’ best friend,” Spence noted. But when it came to the book, she wouldn’t even speak to me.

When the book came out, however, “she went straight to the tabloids,” Spence noted.

“There’s a lot of people that said that they were really close to Callas. But she cut them off at a certain point in her life for a reason,” Spence added, noting that she found people to be territorial and possessive of Callas’ image everywhere she went.

“I am sort of a lone wolf in the Callas community. I had contact with people, but they didn’t really want to get involved when the truth was being presented,” she added. “Deciphering what’s true and what’s not and then having to confront people that believe in this certain ideal. And then telling them they’re wrong, and here’s the evidence. She’s larger than life. She has all these fan clubs and stuff. Everyone’s so territorial. They all saw me as someone coming in and destroying the whole thing they built up.”

One person who Spence found very helpful in her research was Floria Di Stefano, the daughter of Giuseppe Di Stefano. The tenor and Callas were not only a notable on-stage pairing but, per the book, shared a romantic relationship that destabilized the Di Stefano household.

“[Floria] isn’t awed by Callas,” Spence noted. “She respects her, but to her, she’s just her dad’s friend. Or the woman who sort of wrecked her home. She was very level-headed. She was in the minority who saw Callas as this flawed and interesting woman as opposed to the woman in the nice dress who sings.”

She did two years of research and wrote the book at the same time. Per Spence’s admission, the experience was challenging.

“When you look over it, it was really harrowing thinking about how she made it to 53 after all she went through. It’s the darkest story I’ve worked on,” she explained.

However, she noted she had fun discovering unique facets about Callas.

“I love how truthful she is. She has no filter. She is very ahead of her time,” she explained. “In handling Columbia documents, when she was on Ed Morrow, they told her what to say, and when the camera was on her, she did what she wanted. She was always herself. In the 50s, it went against her. She’s honest. When she’s bitching about someone, she doesn’t hide her emotions or who she was. I think that makes her so unique in that time period. She’s not being handled by a publicist or manipulated in a certain way. You get who she is on the day.”

But not everything she discovered about Callas made her comfortable.

Callas previously noted that Peter Mennin harassed her, and that is one reason she did not return to Juilliard.

But Mennin’s family reached out to Spence through their legal reps and said this was not true and that they “resented what tabloids said about her about harassment.”

Given all she knew about Callas and people’s treatment of her, Spence initially gave the diva the benefit of the doubt.

“But I was open-minded enough. They sent me all the letters she had written to him during her time at Juilliard,” Spence noted. “She was crazy about him.”

This put her at a weird and uncomfortable crossroads. What was true? She reached out to Floria Di Stefano, who “looked at [the letters] and said, ‘you see who Callas really was.’ That is Maria when she loves you. She is so jealous and possessive.”

Spence noted that this kind of discovery “was a bit uncomfortable, but it needed to be seen. She is not a saintly figure who is being hard done by. She played a part in her suffering. So I had to open my mind to seeing her in all different lights. Otherwise, you are just fawning over her. I don’t think that she would want that, either.”

Even though the book is out, Spence’s journey with the famed soprano is far from over. She revealed she is working with an Oscar-nominated documentarian on a film about her life based on the book. And there might be more.

As for her next book, she admitted it was “hard to move on from Maria Callas. I started working on a book on Vivien Leigh, but I keep getting pulled back to Callas.”

“I hope that they will see her as a human being and understand that she was this normal woman with this exceptional talent,” Spence concluded regarding what she hopes audiences would take away from the book. “She did say that she tried to be Maria, but Callas takes over. I think it’s time to see her as a normal human being. And I hope that my books bring her story closure. That we’re not sitting with these silly theories about her having a son and other stuff. I don’t think that it’s just disrespectful to Callas but also to Omero Lenguini and his mother. So just understanding that she was this complex woman and not only Callas the artist.”