Wexford Festival Opera 2021 Review: Ein Wintermärchen

Marcus Bosch Leads A Rare Presentation Of Goldmark’s Final Opera

By Alan NeilsonKarl Goldmark was a Hungarian composer who established himself in Vienna in the second half of the 19th century, achieving notable success with a number pieces such as his Violin Concerto No. 1, his Rustic Wedding Symphony, and his first opera “Die Königin von Saba,” which remained in the schedule of the Wiener Staatsoper continuously from its premier in 1875 until 1938. He was praised for his imaginative instrumentation, inventive melodies and use of folk music. However, when he died in 1915, his star quickly faded.

Today he has been relegated to little more than an interesting footnote in the history of classical music, and his operas, of which there are six, are rarely, if ever, performed. There are a couple recordings of “Die Königin von Saba” including one from 2018 conducted by Fabrice Bollon and a 2010 recording of “Merlin,” conducted by Gerd Schaller. It is also possible to view a 2015 Hungarian State Opera production on Youtube of his final opera “Ein Wintermärchen,” an opera which Bruno Walter, who conducted its premiere in 1908, considered displays ‘a weakening of the composer’s powers.’ In other words, a composer worthy of Wexford Festival Opera’s attention.

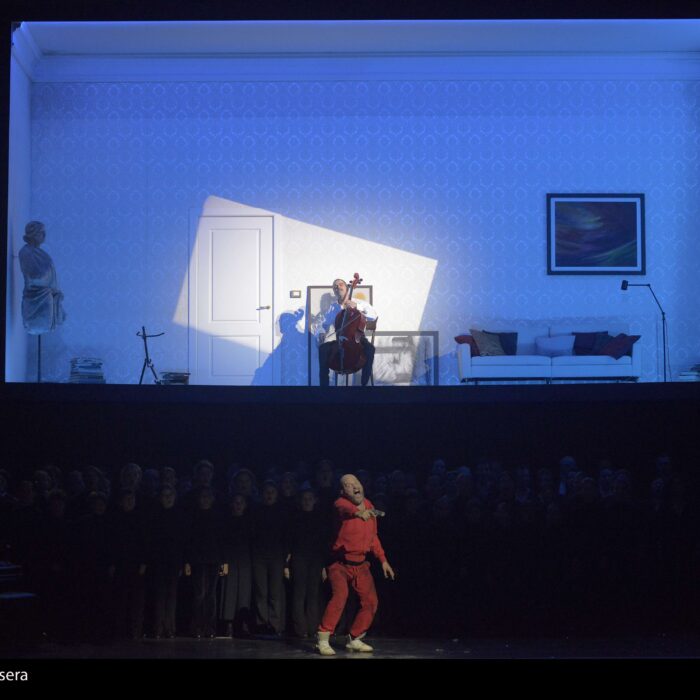

In fact, a production of “Ein Wintermärchen” was scheduled for last year’s festival, but unfortunately, the Irish government’s Covid safety measures put everything on hold. Even this year, it was impossible to go ahead with a fully staged production, so the decision was taken to present it as a concert performance with a smaller sized orchestra. A far cry from an ideal situation, but at least it was opportunity to hear Goldmark’s rarely performed work.

A Meandering Tale Across Time & Place

The opera follows the plot of Shakespeare’s “The Winter’s Tale,” a five act drama with reconciliation and transfiguration as its themes, which meanders between fairytale and realism, with little respect for Aristotle’s unities. The librettist Alfred Maria Wilner, better known for his work with Franz Lehár, compressed the first three acts into a single very intense first act set in Sicily, in which we watch Leontes descend into a jealous rage, imprison his wife Hermione, exile his daughter Perdita, and then collapse into a fit of remorse as he learns that his wife and son Mamillius have died.

Goldmark’s score is tightly aligned to the dramatic ebbing and flowing of the Act, in which his animated rhythms and orchestral coloring successfully create a dark and heavy atmosphere.

Act Two begins 16 years later in Bohemia where Perdita is being raised by a shepherd family. We are now in a very different world from Act One, we have entered into a pastoral idyl of contented peasants and wholesome folk, of grassy banks and sheep-shearing contests. Goldmark’s music breaks completely with that of the first act, switching into a lighter, fresher, breezier mode, in which there is also time for a Viennese waltz as the peasants celebrate. Of course, nothing so simple and pleasing endures, and in this case Perdita has managed to fall in love with Florizel, the son of Polixenes, the cause of Leontes’ rage.

Act Three sees everyone back in Sicily where a full reconciliation takes place, and all is forgiven, even Leontes’ wife Hermione returns, after a lifelike statue of her, made by her friend Paulina, comes to life. The music for the act returns to its more dramatically intense form as the characters reforge their relationships, but then slips into a warmer, more reverential tone as harmony is restored.

A Dramatically Assured Performance From Fritz

The Wexford Festival Opera under the direction of musical director Marcus Bosch produced an animated performance which captured the dramatic twists and turns of the opera, and successfully created its two distinct sound worlds. Bosch also gave careful attention to the changing dynamics which gave the music its unsettling feel, and even without a full orchestral complement, he managed to elicit the score’s interesting array of contrasting sonorities. The balance between the orchestra and soloists and chorus was well monitored and maintained, with only the occasional blip.

Tenor Burkhard Fritz was cast in the demanding role of King Leontes, in which he must convincingly transform his character from a well-meaning friend into a paranoid, irrational beast. Then following the carnage of his actions he must transform again, this time showing his deep remorse. Fritz put in a good performance, in which he sang with an authoritative countenance throughout, and crafted the vocal line skilfully to mirror his extreme mood changes. At the beginning of Act One he was suitably expansive, in which his pleasing tone generated a degree of warmth, but with his descent into jealousy, his tone darkened slightly and his presentation became more animated, with greater dynamic and emotional contrasts. In Act Three, his singing took a more lyrical quality, reflecting his more balanced state of mind and the general feeling of reconciliation which envelops the scene. It was a performance which convinced, and displayed his talent in a good light, notwithstanding the occasional strain in the voice which was evident in the more demanding passages.

As Polixenes, one of the principal objects of Leontes’ ire, was baritone Simon Thorpe, who produced an inconsistent performance. Generally, passages of recitative were well-delivered, in which he displayed sensitivity to the meaning of the text, although his vibrato was a little too heavy for some tastes. Moreover, he did not shirk from digging out the emotional nuances of the character, with which he identified closely. Where he failed, however, was that the amount of effort he put into his singing was far too apparent, at times verging on bluster, and which could sound somewhat disconcerting.

Soprano Sophie Gordeladze produced an excellent performance in the role Hermione. She possesses an appealingly bright timbre, a secure upper register, wonderful versatility, and sings with an impressive degree of control and expressivity, which allowed her to successfully captured her characters’s complex and shifting emotions. This was particularly effective in revealing the affection she has for her children: her lullaby was sung with such love and sensitivity that its interruption was all the more violent.

A Voice Awash With Color

Hermione’s friend Paulina was played by mezzo-soprano Niamh O’Sullivan, whose intelligent use of her sumptuously coloured pallet opened up wonderfully rich textural contrasts, which brought depth and nuance to her singing. It was also a very expressive and dignified performance, yet one that never descended into overstatement, allowing her clear articulation and use of subtle dynamic, coloured and emotional inflections to successfully portray Paulina as a steadfast, morally certain character.

Soprano Ava Dodd from the Wexford Factory young artist programme was cast as Perdita. She possesses a strong, fresh voice with a engaging timbre, which she used successfully to develop a sympathetic portrait of the young lover in an energetic performance which belied her relative inexperience. Her ability to spin out lyrical, bright, beguiling lines and deliver pleasing coloraturas with apparent ease was particularly impressive.

Perdita’s lover Florizel was played by tenor Daniel Szeili. Unfortunately, he appeared somewhat ill at ease in the role and did not convince. There was no sense of a relationship of any sort with Perdita, and the intimate scene from Act Two was a very one-sided affair. His singing, especially in upper register, lacked focus and sounded threadbare on occasions.

Antigonus, who is responsible for abducting and exiling the child Perdita 16 years earlier, was parted by baritone Jevan McAuley who produced a lively, well-crafted performance.

Sheldon Baxter produced a pleasing performance in the small role of Valentin, in which he managed to inject a degree of humour into his behaviour as he whined and pleaded for his life.

Baritone Rory Musgrave in the role of Leontes’ cupbearer Camillo produced a reserved reading, which would have benefited from stronger projection.

Treble Conor Gahan was understandably nervous in the role of Mamilius, but did himself proud with a well-sung performance.

The chorus of Wexford Festival Opera, under the direction of Andrew Synnott, produced a fine performance from which many of the minor roles were cast, many of whom gave very good performances. Unfortunately, however, it was not always possible to identify the individual singers by name.

Although this was a very interesting and enjoyable performance, it left one feeling a little frustrated, even dissatisfied. Opera is a visual experience, not just an aural on, and it is the meeting of these experiences which makes the art form what it is; deprive the audience of the visual, and part of the meaning can be lost or remain hidden, especially when the opera is not well-known, as in this case. If this production had been planned as a concert performance from the outset, then the disappointment would have been assuaged, but by knowing that it was to have been staged, questions continually came to mind about how parts would have been staged or clarified, or characters presented. The reduction in the size of the orchestra likewise immediately brought to the listeners’ attention questions about changes to the textural quality of the music. Such observations aside, it was a successful presentation.