The Ring in San Francisco – William Berger Confronts Racism in Wagner’s ‘Ring’

By Lois SilversteinSan Francisco Opera is in the midst of its month-long festival dedicated to Wagner’s “Ring Cycle.” In the coming weeks, Lois Silverstein will explore her experience not only revisiting the 2018 opera production, but several of the events and panels presented by the company.

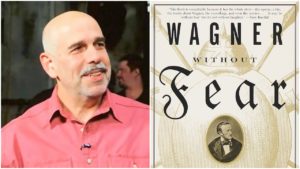

William Berger of the Metropolitan Opera, a popular lecturer on opera, and author of “Wagner Without Fear” and “Opera As Metal” introduced issues of Wagnerian controversy in his Virtual Ring event, with the subject of racism at the center of it all.

“The Ring is racist,” Berger said, and he went on to outline racism as the problem of exclusiveness, of putting one set of people against each other. For instance, when Wagner spoke, in the 19th century, of the race of Aryans, he was speaking of a group that didn’t really exist. Wagner’s race consisted of dwarves, giants, demi-gods, gods, humans. What he did in The Ring was set these people against each other and thus establish the story and its tensions. Always, Berger said, Wagner needed “untermenschen,” i.e., bad guys, an enemy. In The Ring, someone always gets stabbed in the back, and not by accident. It differs in Verdi, Berger added. The whole mood is not the same kind of belligerence.

From the early days of his career between 1800 until today, Wagner has provoked heated discussion: he was revolutionary in his music as well as his politics in his early days. We ask the question often, “Who was he fighting on behalf of?” In politics, the revolutionaries; in opera, the traditionalists. and if so, who, actually was he fighting on behalf of? Was he a chauvinist? How was he anti-semitic and in what ways? Was it prevalent in his music itself? How shall we interpret the fact that the Nazis, and Hitler in particular, commandeered his music on behalf of their megalomanic wish to rule the world?

Wagner’s work is racist because it is based on exclusion. When opera subjects and operatic performers are selected based on particular racial persuasions, we are dealing with exclusivity. Berger contended that when human conflict is predicated on exclusivity solely, we are dealing with racism. In Wagner’s case, critics have called particular characters in The Ring, for example, examples of this anti-semitism. Examples in The Ring include Hagen and Alberich; one can’t overlook Beckmesser in “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg,” either. Particularly, because Hitler idolized Wagner, perhaps as he wanted his Germans to idolize him, which they came to do, when we deal with Wagner, we can’t ignore this horrific bias and its detrimental impact.

When a production is a product of a point of view, it can become a political battlefield. “The letter killeth, the spirit gives life.” There is no ethic without an aesthetic. Hence, the original crime of The Ring is a crime of originalism. As Berger said, originalism is a form of fundamentalism, and the limitations of fundamentalism reveal the ongoing process of exclusion.

In the opera, Wotan wants it both ways – to rule the world and to insist on values and ideals that oppose this. These cannot be held at the same time. Worship of the god and a human Wotan cannot be held at the same time. You have to choose. Needless to say, Wotan doesn’t want to. In order not to destroy the gods, he must allow them total sway; not to allow them total sway, requires openness to other ideas. This Wotan rejects.

When we come to the Wagner worship and the fossilization of productions, Berger talks of early scenic directions Wagner included in his scores, reflecting his early aesthetic ideas. To sustain these stage directions after Wagner’s time, for instance, Berger sees another aspect of racism. Instead of seeing in The Ring, for instance, as an opportunity to explore new ideas, where we can blend the old with radically new perspectives, as a laboratory of exploration, traditionalists prefer to eradicate what might evolve with what was set down at the beginning. Evolution favors the most adaptable, Berger stated, not the most rigid.

He mentioned, with some enthusiasm, however, that after the only production of The Ring that Wagner saw in 1876, the composer said that the next time, it would be entirely different. Is this a sign of fossilization? On the contrary. Hardly. It is the sign of an artist who wants room to develop what he has created, with an eye to move it on further. This, he said, was a good stopping point to explore what part we each play in the controversy of producing Wagner. Wagner died. Did that mean we needed to fossilize his artistic vision?

Categories

Special Features