Q & A: Mark Adamo on ‘The Lord of Cries,’ John Corigliano & Santa Fe Opera

By Francisco SalazarOn July 17, “The Lord of Cries” will have its world premiere at the Santa Fe Opera.

The work by real-life couple Mark Adamo and John Corgliano is said to be a juxtaposition of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” and “The Bacchae” by Euripides. James Darrah will direct the work which will star Anthony Roth Costanzo and David Portillo, among others.

OperaWire spoke to librettist Mark Adamo, who is also known for his opera “Little Women” and “Becoming Santa Claus,” about collaborating with Corgliano, writing the libretto and the prospect of world premiering “The Lord of Cries” at the Santa Fe Opera.

OperaWire: Tell me about when this concept came about and when did you guys begin working on it? How did it develop over time?

Mark Adamo: Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” has been adapted, well or poorly, for over a century. Most adaptations blur the novel’s message, which it shares with Freud’s theory of the return of the repressed; its warning to honor our animal nature lest it turn monstrous in imprisonment and rise up to destroy us. Each day brings fresh proof that our culture must relearn that lesson. We scoff when we read about this or that moralizing priest or senator dragged, blinking, from the crack den or the mistress’s flat. But Stoker hints at the real anguish, the longing for virtue, experienced by people so terrified. I had been invited to consider Dracula for the opera house, and had struggled with it; using the vampire, as many have, as a romantic metaphor for sexual dissidence seemed, in 2021, a played card. But people who look to monsters, rather than their mirrors, to justify their fears are still everywhere with us. An opera about them might be one worth writing.

When I told the librettist, William Hoffman of my thinking, he said, “You realize you’re writing ‘The Bacchae,’ yes?”

I hadn’t. But then I read the play; and realized that “Dracula” is virtually an English translation of Euripides’ great tragedy, with only a false happy ending distinguishing the novel from the drama. Both the vampire and the god Dionysus are violent, ecstatic, sexually disordering forces from the East, who threaten to inflame the women of their respective cities (Thebes and London) to frenzy unless their powers are acknowledged. They are each resisted by a young, brittle leader—Pentheus in “The Bacchae,” John Seward in “Dracula”—new to his power and fearful in his desires, whose conception of virtue is so rigid that he breaks rather than bends. Unlike the novel, “The Bacchae” has a simple, clear story: the god gives the leader three chances to acknowledge his birthright, and only exacts his vengeance when refused.

I knew that mapping the stuff of the book onto the plot of the play would give to “Dracula” the strong structure and, crucially, the moral stature the novel lacked. A lovely bonus was that Dracula’s Victorian frame, more familiar to a contemporary audience than 5th-century Thebes, would also make the concerns of The Bacchae clearer to such an audience than its original Greek context would.

OW: Once the libretto was written what were some of the ideas for the music? How did it develop? As a composer, did you have any say in the music?

MA: As he did in his first opera, “The Ghosts of Versailles,” John portrays two strata of characters in “The Lord of Cries” in sharply different musical idioms. While the music for the humans in the new opera doesn’t refer specifically to other composers they way the mortals’ music in “The Ghosts” engaged with Mozart and Rossini, the suffering and emotionally corseted Victorians in “The Lord of Cries” sing often in formal, triadic, musically contained paragraphs that couldn’t contrast more starkly with the wild, vocally elaborate, and often percussive music John has devised for the Dionysians. That music paints the god and his revenants in uncanny waves of sound that often escape meter and harmony entirely. But, even within the neo-Victorian idiom, the human characters share, Lucy’s music isn’t Seward’s or Jonathan’s; similarly, the themes for Dionysus and the Furies are related but individuated. Fortuitously, John found early on that the letters of the title of the play—B-A-C-(C)-H-(A)-E—each had analogs to pitch names. (Traditionally, B is used to name the pitch B-flat, while H denotes B-natural.) He wondered if using the pitches in sequence could build a sonority for the immortals that would both characterize them expressively and refer, however obliquely, to the opera’s source—just as the musical spelling of Bach’s name has been used by composers from Schumann through Schnittke. So now there is, quite literally, a “Bacchae chord” which recurs through the score at certain key moments.

I didn’t specifically give John any guidance in composing the score: I didn’t have to! And it was a delight, as a librettist who’d only worked with his own scores, to see what another composer—even one I knew as well as John—would make of my play. I did, though, have two advantages when writing this libretto. The first was my familiarity with John’s method of blueprinting the structure of a piece of music before deciding on its materials. The second was that I had devised a similarly architectural method of designing both text and score to the four operas of my own I’d completed before embarking on the script to this one. So I was able to build into the language of even the first draft the kind of thematic and textural possibilities I knew John would need.

OW: Were any of the roles written for the cast members? What has it been like to collaborate with the cast?

MA: The three singers we knew before embarking on the project were the peerless Anthony Roth Costanzo, to whose protean instrument and fearless dramatic instincts the title role was fitted; the sumptuously voiced bass Matthew Boehler, for whom I had composed a leading part in my previous opera, “Becoming Santa Claus,” and whom we knew would make a magisterial Van Helsing; and the shape-shifting bass Kevin Burdette, who can range from comedy to gravitas in a single role and who is truly luxury casting in the speaking rôle of the Correspondent.

We had known of, but never worked with, the marvelous duo of Jarrett Ott (John Seward) and David Portillo (Jonathan Harker), and every day they surprise us more with the iridescent vocal colors and soulful dramatic shadings they bring to even the briefest phrase.

OW: Why is Santa Fe Opera the best place for this world premiere?

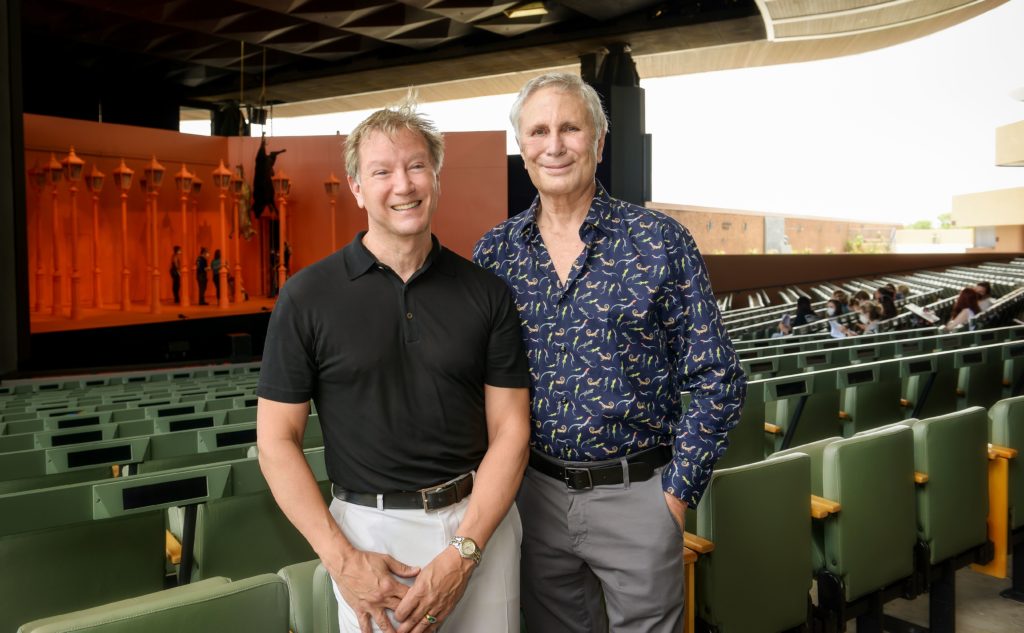

MA: Santa Fe has long been one of the most distinguished companies in the U. S., and one of the few to make a robust contemporary-opera program the cornerstone of its programming from its beginnings. Its culture combines the rigorous professional standards of a world-class urban company with the warmth and easy feeling of a summer festival: Alexander Neef, his successor David Lomeli (whom I knew from the Dallas premiere of “Becoming Santa Claus”) and Robert Meya have understood and supported “The Lord of Cries” from the start.

And Santa Fe Opera’s unique outdoor theatre is not only beautiful in itself, but—built as it is into a rugged desert landscape—evokes the sort of Greek amphitheatre in which “The Bacchae” might have been given its premiere.

OW: Tell me about working with James Darrah and has he fulfilled both of your expectations for the work?

MA: James’ distinction as a director is that he is equally gifted in working deeply with actors—in close-up, if you will— and devising large-scale ”long-shot” stage pictures that tell as much of the story as his actors do. Also, “The Lord of Cries” isn’t a dance piece, but it often needs a kind of movement from its performers that often borders on the ritualistic; a kind of surrealism in its stage life that matches the aural surrealism of John’s score.

James has achieved that brilliantly here, I think: he’s also a warm presence and a generous colleague. He and our conductor Johannes Debus—who knows what every note and rest of John’s score is supposed to do, and has imparted that knowledge to his stunning cast and orchestra— make a terrific team.

OW: What are some of the future plans for the work?

MA: Well, we’re still in tech week, so the principal plan is to get to opening night! But there is already interest both in other mountings and a recording: we are standing by…

OW: What does it feel like to have your opera premiering after such a long pandemic?

MA: The principal feeling is gratitude. Both John and I have been extraordinarily lucky in our lives in the opera house, in that we’ve inevitably worked with artists secure enough in their own gifts to be generous both to their colleagues and to us. Even given that happy history, though, this experience is special. I think the pandemic reminded us of how precious what we do is, both to ourselves and to others.

It also reminded us of the difference between what looks important and what actually is important. The company of “The Lord of Cries” is working at once with glittering artistry and open hearts. You don’t forget an experience like that.