Opera Meets Film: How Peter Weigl Explores Dvorak’s ‘Rusalka’ on Video

By John VandevertWe all know Disney’s rendition of “The Little Mermaid,” and are familiar with its transformation of Hans Christian Anderson’s oft-disturbing 1837 fairy tale into a heartwarming, family-friendly story of love and adventure.

The original narrative is far more Wagnerian than Mozartian in dramatic tenor, due to Anderson’s synthesis of intense pathos with virtuous rebirth. In the Disney version, Ariel—who is unnamed in original 19th century fairy tale—wishes to explore the “world up above,” and forfeits her prized voice in order to gain the necessary apparatus—legs—to seek her love, Prince Eric. Unlike Anderson’s version, while Eric does act duplicitously at times, it is not intentional, and his behavior is later forgiven following his heroic defeat of the sea witch antagonist Ursula. In the original tale no such amends are made and the Little Mermaid is forced to recognize the flaws of her strategy. In the end, however, her virtuous behavior—refusing to kill the duplicitous Prince and his human Princess—earns her ever-lasting peace. Disney’s deviations from the original storyline, and their assassination of the true teachings infused within Anderson’s story, have been discussed at length before.

The question raised here, and which is the most important for discussion of Antonin Dvorak’s embodiment of this tragic, Isolde-like heroine in “Rusalka,” is “How much responsibility do we have for the development of our character? Do we choose to be virtuous or not, are we born virtuous and then are corrupted, or is there more going on?”

According to Maria Tatar, Anderson’s interest in mutability, the flux of self-identity, and the individual’s power over their circumstances lay at the heart of this “fairy tale”—although, despite the whimsical characters, the Little Mermaid is less a fantasy and more correctly an “allegory.” She is all of us and her story represents our own desires to truly know ourselves and the derailment we often face at the hands of trickery and deceit. Dvorak’s immortal opera “Rusalka,” his ninth and penultimate, encapsulates this dichotomy of the human spirit perfectly. Amidst the juxtaposing forces of orchestral word-painting, sublime lyricism and sacred musicality, calculated sophistication, functional passages, and a breadth of idioms and leitmotifs of both national and narrative significance, an astute listener finds themselves at odds. Dvorak’s navigation between extreme emotionality and solemnity, his dance through emotional liminal space, and his ability to express the universal desire for knowledge through human means while producing a largely inhuman experience is beyond my comprehension.

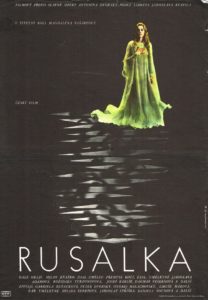

Staged performances of “Rusalka” vary in their proximity to reality. Paris National Opera’s famous 2002 production featured a white hotel room-style stage set while just two years later the MET’s 2004 production featured a convincingly-recreated swamp with the iconic scraggly tree that Rusalka climbs to deliver her soliloquy to the moon. Bayerische Staatsoper’s controversial 2010 production was entirely left-field and used underground tunnels, a fish tank, and a mental asylum, while Teatro Real’s recent 2020 production was more conservative, using palatial interiors and intruding rocky outcroppings to showcase the juxtaposing forces. But all pail in comparison to the 1977 cinematic film under the direction of Petr Weigl, with music by the Bavarian Radio Orchestra. Shot on location in Czechoslovakia, one is transported into a universe of myth and legend.

Once upon a time…

Weigl’s Universe

Petr Weigl’s ability to conceive of opera as fully-realized reality and utilize the music in a diegetic way, embodying his character’s inner-most thoughts while exploiting costuming, color, atmosphere and lighting, is laudable in its own right. A cursory look into Weigl’s fame reveals that this film helped propel his career forwards due to the naturalistic manner in which he conveyed his operatic narratives onscreen. In the words of one anonymous commenter, “His works are elegant, sometimes sensual, occasionally mixed with a dose of eroticism, well-cast with attractive and convincing actors with little exception.” One finds this to indeed be true, as the film dances along the line between sexuality and innocence, duplicity and genuine merriment, aged shrewdness and naive optimism, nobility and carnality in such a way as to blur the distinction between them. Right at the beginning of the film we see the woodland nymphs engaged in their revelries dressed in sheer cloth which leaves both little and a lot to the imagination, though such considerations are not on their mind.

This whimsy is juxtaposed by Vodník’s lascivious yet playful attitude regarding them. One of the nymphs even kisses him on the cheek before bashfully running into the darkened forest with her companions. This opening scene, accompanied by a lively and energetic score, continues to be one full of contrasts. Once the nymphs exit, Vodník the water goblin’s entire attitude changes. He becomes more austere, looking down thoughtfully at a flower. This signals, perhaps, his desire for true love, much like his daughter. This moment emphasizes that the pursuit of pleasure is not all there is in life: even the most beautiful women are not enough to replace genuine affection. While many interpret the opera’s plot to be about the duality of desire in all its forms, the power of feminine sexuality and its exploitation by masculine influence, or the difficult but necessary journey towards self-enlightenment, Weigl uses the juxtaposition between the natural—woodlands, swamp, forests, flowing pastures—and the artificial—tailored gardens and palaces—to paint a very clear picture of the ramifications of excessiveness in all its forms. Perhaps the most important allegory within “Rusalka” is to not desire the external too much, for one may end up losing themselves in the process.

Practically speaking, Weigl’s cinematic universe for “Rusalka” spans two locations: the swamp and the palace. The swamp, however, is portrayed in vastly different manners as the story progresses. The first time we see this natural abode it is Rusalka’s pre-enlightenment realm. It is nestled within scenic forests and imposing, rugged terrain. From rock-faced watering holes and swampy shore-lines, through expansive forest-ringed grasslands, to the mystical darkness of the mysterious water witch Ježibaba’s grotto and Vodnik’s pond, Weigl casts nature as something surreal. It is beyond the reaches of human life and yet inevitably shaped by the same emotions as human life. The second location are the lands of mankind. These are epitomized through 17th-18th century Francophile aristocratic plushiness complete with contrived Baroque palaces, manicured gardens, outdoor balls, casual racism, and the weaponization of nature as a tool for mankind’s own hedonistic devices. Though there are only two locations, there is a third atmosphere which Weigl creates: it is the swamp after Rusalka has been awakened to man’s cruelty by the fickle Prince’s wandering eyes. Rusalka realizes the Prince’s infatuation with the other woman—the “Foreign Princess”—is merely physical but it is nonetheless damning. Realization dawns on her wedding day, as she stands in a field awaiting the wedding ceremony: standing in a liminal zone between the ordered palaces and disordered nature.

The film drastically changes at this juncture. We return to the forested swamp world where, still dressed in her wedding attire, Rusalka (like so many tragic opera and ballet heroines before her, such as Giselle, Odette, Lucia, and Cio-Cio San) suffers a psychological battle between her expectations and the results of her forced enlightenment. The way that Weigl brings together all the separate strands of “Rusalka” into the film’s final third—the divinely natural and indulgently manmade crashing together—is exceptional. There is a moment after Rusalka flees where Weigl has her caught between the gaze of the Prince and Princess at one end of a stone corridor and Vodník lurking in the marsh at the other end. She runs to her father, and the harsh contrast between her blanched white dress and Vodník’s gray-toned garments, along with the Princess’ vibrant orange courtly dress and the Prince’s silver robes demonstrates where the Prince’s true passions lie and the corrosiveness of the human penchant for pleasure. Weigl’s manipulation of scenery, costume, dramatic pacing, and narrative rhythm are exceptional. There is yet one more point to be made, however.

The “Singing” Actor

The film follows the conventional model of many operas-turned-films: the singing is dubbed, the music sung by an alternative cast of individuals, while those onscreen lip-synch and gesticulate the sounds of the singing. Though I understand why this is necessary—some singers are dreadful actors while most actors have less than optimal voices for singing, let alone singing operatic repertoire—the danger is that these two art forms can be so separated that the human element of each becomes lost. The actors no longer have a real reason to act and the singers are simply going through motions without any of the work’s innate purpose. This disintegration of motivation and the pitfalls of dubbing singing over acting is implicitly clear when one has watched a film where its actors genuinely sing while engaged in the histrionics of the story. Live opera is the greatest example of the successful merger of the two artforms, where the singer is the literal embodiment of the composer’s vision and must participate with their whole body in the activities of that character.

While it is perhaps not fair to compare live opera experiences with filmed ones, when a director cuts the two artforms in half—having one cast who acts and another who sings—while the impact may be small, it is difficult to watch the film as Weigl intended. It would have been more effective to have a dance-based or non-verbally acted film run alongside the orchestrated variation of this score, much in the way Beverly Baroff set the sublime music of Ravel’s “Pavane for a Dead Princess” to outdoor ballet. Weigl must have utilized this dual cast system for reasons more pragmatic than dramatic. The singing would have sounded awful as the acoustics in the swamp and woodland would have not served anyone well, while the singers were perhaps not actors or did not fit the aesthetic image of what Weigl wanted. Having said that, while the first point is obvious to anyone who has attended an outdoor concert, the latter two points allude to a pernicious and ubiquitous problem in modern operatic productions, whether filmed or not.

Singers are no longer taught how to truly emote through their fingertips, eyes, eyebrows, and the micro-movements that create the living embodiment of the role. All one has to do is watch singers from the “Golden Age” of opera—anything pre-2000s, really—and then see singers now to recognize that exaggeration or austere stillness is not the same as genuine acting. The third point I mentioned, regarding the aesthetic image of what Weigl wanted, is also incredibly important. As opera-loving audiences we want to be lured into a world of the make-believe, but deeper than that, we want to see what we wish we were or wish we were not, in order to make our present condition less miserable and our future aspirational. When presented with tantalizing and stimulating onstage aesthetics, our minds perk up and we are swept up in the flurry of emotions that provocation brings.

No matter how beautiful Dvorak’s opera is, the underlying message seems to be that one is not truly free unless they see the illusion before them, and only through undergoing suffering can someone be truly liberated. Rusalka’s desire to see the “world up above” was based on an ideal and an illusion, and when faced with the truth her dream was destroyed. She had to face reality: that her place was not above but below. Yet from another angle, like Rusalka notes at the opera’s conclusion, despite her suffering she is still grateful for the Prince: he allowed her to feel what true love was like. Having now experienced the extremes of affection she is free, although never without the lasting influence of her “awakening.”

In many ways, “Rusalka” mirrors Orff’s “Carmina Burana,” destroying the sanguine image of nature. This ostensibly benevolent force is far more dispassionate than it is caring. The wheel of fate waits for no person, living or dead, supernatural or otherwise, and by coming face to face with Rusalka’s suffering we realize that our desires to control anything outside of our own consciousness are inevitably doomed to fail if we do not recognize the barriers to our control.

Petr Weigl’s film capitalizes on this quandary, and juxtaposes the imperialistic lifestyle of the aristocracy with the mythical, sylvian realm of the Czech countryside, showing how both universes were ultimately not that different. Despite Rusalka’s fantastical life she remained unsatisfied and as a result outgrew her innocence. Weigl teaches us that we can never outrun ourselves.

Categories

Opera Meets Film