Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra 2018-19 Review: Salonen’s Stravinsky – Myths

An Immersive Journey Into Stravinsky’s Dramatic Qualities

By Gordon WilliamsI have long mulled over Stravinsky’s concept of theater and his ideas about the relationship of words and dance to music. This concert may have helped me understand it.

Led by their Conductor Laureate Esa-Pekka Salonen, the Los Angeles Philharmonic presented the 1947 ballet “Orpheus” and 1934 cantata, “Perséphone,” in what was the third and final concert in a mini-series entitled “Salonen’s Stravinsky.” Previous concerts had been promoted as Rituals (“Funeral Song,” and the ballet scores “Agon” and “The Rite of Spring”) and Faith (including works such as the “Requiem Canticles”).

New Worlds

Having left behind the extreme and even violent expressiveness of his earlier Russian ballets such as “The Rite of Spring,” Stravinsky presented an almost bleached vision of the Orpheus myth in his 1947 ballet. In the first half of this concert, we experienced the work even without George Balanchine’s extremely spare original choreography, which I have only ever glimpsed on film. There were surtitles to guide us through the basics of the plot – projections of captions that occur in the score: “Orpheus weeps for Eurydice. He stands motionless, with his back to the audience;” “The Angel [of Death] leads Orpheus to Hades;” “Orpheus tears the bandage from his eyes. Eurydice falls dead.” And it was fascinating to read those while listening.

The Philharmonic might just as easily have played the work without any visuals, of course. And then I would have had to decide how much the music, alone, speaks to me. As it was, I found myself initially wishing for more, and I say that understanding that Stravinsky fell out with André Gide who wrote the text for “Perséphone” (which we were to hear in the second half) because Gide in effect regarded music as subservient to the other elements. He didn’t understand that Stravinsky was trying to achieve a union of music with text and words/action that was more than music merely illustrating the narrative, a distinct kind of fusion.

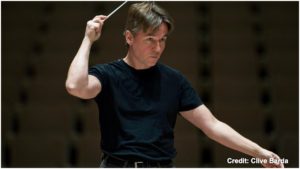

I stress however that I enjoyed the sheer sound of this “Orpheus.” In Salonen’s hands I found myself savoring Stravinsky’s extremely precise instrumentation, the fact that chords had been “tuned” to the precise grain. I was constantly struck by the instrumental balance – loved the piquant instrumental solos of artists such as principal oboe, Juliana Koch – and even reflected on the fact that in a Stravinsky piece there is a drama in the orchestral seating, noticing how, at one point in the Apotheosis near the end, tension was being held across the orchestral space by the front desk of violins downstage, two horns up the back and a trumpet and harp off to the side.

There was a warmth to this playing (a depth in the strings actually) that surprised me, particularly in its telling contrast to the hard, white (and effective and appropriate) lighting of James F. Ingalls. And as I watched Salonen’s fluid hands I suddenly found myself thinking that the expressive intention in Stravinsky actually doesn’t end with the sound-envelope but with the gesture. Could that be why Stravinsky once said that he was “more interested in [ballet] than in anything else?”

That thought was soon put to the test.

A Complex Combination

“Perséphone” is one of those works of Stravinsky that are part-ballet, part-play, part-oratorio. And the Los Angeles Philharmonic does these semi-staged presentations very well, in my experience.

Here the stage held my attention. When I say stage I mean “ritual space” because, in director Peter Sellars’ conception the chorus (a highly engaged Los Angeles Master Chorale) sat – barefoot and in colorful casual tops – on three sides of a quadrangle behind the orchestra watching and commenting on the actions of tenor Paul Groves (as Eumolpe) and members of the Amrita Performing Arts, Cambodia (Sam Sathya as Perséphone, Chumvan Sodhachivy as Déméter, Nam Narim as Démophoon and others, and Khon Chan Sithyka as Pluton) as they delineated their story in Ingalls’ warm rectangles of light.

My takeaway of Stravinsky and Gide’s “Perséphone” is that Persephone, daughter of Demeter and Zeus, peers into the calyx of a narcissus flower where she sees the suffering of the inhabitants of the Underworld. Out of compassion she descends to Hades but her mother, Déméter, goddess of corn amongst other attributes, mourns her loss and plunges the world into famine. Perséphone is allowed to return to earth but, yearning for Earth, she has tasted food in Hell, a taboo. Therefore she must return to Hades for a part of each year (thus: winter). But the work celebrates her return to Earth each spring; a more joyous event than the cataclysmic splitting of ice memorialized in the young Stravinsky’s earlier “rite of spring”.

From my understanding, the White Russian Stravinsky resisted the humanist tendencies in Gide’s understanding of the myth, which emphasized Persephone’s descent out of compassion rather than from being abducted, “as Homer tells us.” He did not see eye-to-eye with Gide’s Leftist sympathies, but the Frenchman Gide himself was disillusioned after visiting the USSR and Sellars’ Director’s Note mentioned how the Cambodian dance in this performance was a living example “of resilience, recovery, and regeneration” after the “famine, cruelty and mass murder” of the Khmer Rouge, a more recent Totalitarian regime.

I found myself thinking less of Pol Pot in this performance, however, than of the “Ramayana” in which Sam Sathya has appeared in performances at Angkor Wat. I felt that this performance truly admitted me to a celebratory ceremony of Spring, and a true ritual. And I have to say I am thankful to the Los Angeles Philharmonic for so often reminding me that a concert is something more than a recycling of repertoire.

Perfect Stravinskian

But I still do want to single out elements of the performance, having been moved by Sam Sathya and Chumvan Sodhachivy’s pas-de-deux as mother and daughter, Cécilia Tsan’s beautiful narration (“inquiète”, “décoloré”…the sound of her voice still rings in my ears), and the perfect Stravinskian tenor, Paul Groves. Not only did his clear, golden sound keep me focused, I admired his sense of movement, his use of the staff, which became in his hands a powerful symbol, almost perhaps, of an ability to conduct the audience back and forth between worlds.

Some years ago I asked a former premier danseur what he thought of Stravinsky. He said he found Stravinsky’s music very emotional. That puzzled me because so many musicians had told me they find the Neo-Classical works (of which “Orpheus” and “Perséphone” are examples) distant and cold. Perhaps the dancer was thinking of the gestural suggestion. In any case, I found this performance touching.

When the adult chorus, sitting around their quadrangle, sang directly to the children, the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus, as if to say, “Listen to this, children”, and when they all raised their hands at the words “reborn,” it was terribly affecting. Everything about this interpretation hung together even though, on paper, it seems such a mix of disparate elements – narrator, tenor, dancers, chorus, orchestra.

For that I must give credit to Sellars and Salonen who made of this such a coherent whole. I hope I get to see this interpretation of “Perséphone” again. I want to enjoy it as a simple communicant.