La Monnaie 2025-26 Review: Benvenuto Cellini

By Ossama el NaggarThough “Benvenuto Cellini” (1838) was Berlioz’s first opera, premiering five years before Wagner’s “Der fliegende Holländer” (1843), thirteen years before Verdi’s “Rigoletto” (1851), and two decades before Gounod’s “Faust” (1859), the work sounds positively avant-garde compared to contemporaneous works and even compared to those written long after it. The most astounding innovation was Berlioz’s use of syncopation, especially in his incredible “harmonious dissonance,” omnipresent in “Benvenuto Cellini” as an allusion to the life of a true artistic creator. Over four decades later, Bizet used this innovative device in his admirable Act Two quintet “Nous avons en tête une affaire” from “Carmen“ (1875).

In “Benvenuto Cellini,” librettists Léon de Wailly (1804‑1864) and Henri Auguste Barbier (1805‑1882) wrote a highly fictionalized account of the eponymous Renaissance sculptor’s life. Cellini’s most famous and magnificent work, “Perseus with the head of Medusa,” was in reality commissioned by Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519‑1574), Duke of Tuscany, not Pope Clement VII (1478‑1534), as the libretto states. De Wailly and Barbier created a sympathetic portrait of Cellini; a man who was, in reality, depraved by even today’s liberal standards, who derived pleasure from humiliating his sexual partners and who was condemned several times for sodomy and thrice for murder. Given his immense talent, the powers of the day judged it more worthwhile to indulge his sociopathy. In the opera’s libretto, the Pope pardons the sculptor with the revealing words, “Puisque Dieu lui‑même a béni/Et tes travaux et ta hardiesse/J’acquitte à l’instant ma promesse,/Et te pardonne, ô Cellini.” This is an allusion to the (albeit immoral) notion that talent supersedes crime and absolves all.

The action takes place in Rome, circa 1532, in four scenes over three days: Shrove Monday, Mardi Gras, and Ash Wednesday. Balducci, the Pope’s treasurer, is concerned that the Pope has commissioned the unconventional Florentine Cellini over his future son‑in‑law, Roman sculptor Fieramosca. Cellini manages to access the bedroom of Teresa, Balducci’s daughter, through her window. His rival Fieramosca also enters and overhears Cellini’s plan for Teresa’s elopement with him at Carnival. Cellini and his assistant Ascanio are to be dressed as monks, who will take her away in the chaos of Carnival. As Balducci returns, Cellini escapes, but Fieramosca is caught and the neighbours are called on to dump him into a fountain. At Carnival, Balducci and Teresa attend a play about King Midas, in which the sovereign is made to look like Balducci. Commedia dell’arte characters, Pierrot and Arlecchino, compete for the king’s attention. Teresa is confused when she sees two sets of monks, Cellini and Ascanio, and Fieramosca and his friend Pompeo; the latter wearing the same disguise to outplay the former pair. In the ensuing imbroglio, Cellini stabs Pompeo to death and is captured, though he escapes. Fieramosca, wearing Cellini’s disguise, is arrested in his place. The Pope appears in Cellini’s atelier, threatening to hand the commission to another. The audacious Cellini takes a hammer and threatens to destroy the mold, at which point the Pope promises to pardon Cellini if he promises to cast the statue that very evening. But, should he fail, he will be hanged, as iterated in the lines: “Si Persée enfin n’est fondu, dès ce soir tu seras pendu.” At the foundry, the smithies threaten to stop work until they get paid. Teresa tries to reason with them to no avail. When Fieramosca attempts to bribe them to stop work, they are enraged, reasserting their loyalty to Cellini. When they are short of metal, Cellini orders all sculptures in his studio to be smelted. Come the evening, the statue has been successfully cast. The Pope then pardons the triumphant Cellini, finally reunited with Teresa.

With such a story about creativity and the setting in 16th-century Rome, there are many possibilities for an intelligent, talented director. Alas, Brussels’s venerable opera house, La Monnaie, assigned the task of the rare opera’s Belgian staging to Thaddeus Strassberger, who, while a creative mind, is purveyor of a mauvais goût that is hard to digest. Indeed, several left at intermission and their decision was far from capricious.

During the overture, an appealing video (Greg Emetaz) of images from the fresco ceiling of the theater came to life to announce an unconventional (AI-supported) creation. Since the opera concerns creativity, Strassberger introduced four of the nine muses, most likely Calliope (Epic poetry), Euterpe (Music), Terpsichore (Dance) and either Melpomene (Tragedy) or Thalia (Comedy). This was enchanting, but as they were omnipresent, they distracted from the performance (seen February 3rd). After their debut as AI-generated images during the overture, they were portrayed by actors with exceptionally convincing make up and costumes throughout the rest of the performance. It is possible two of the four actors were cross-dressing men. This particular device was presented as a Strassberger “innovation” throughout the production.

The Commedia dell’arte play in Act Two was transformed into an arguably tasteless drag show. This dreary interlude added a good fifteen minutes to the proceedings. Visually flamboyant, it featured two queens dressed phantasmagorically in outfits that channeled Fellini’s “La città delle donne” (1980), though without coming close to his genius. Arlecchino had an enormous bosom while Pierrot wore five sets of breasts, alluding to the she-wolf Lupa who nursed Romulus and Remus, Rome’s founders. Cassandro, a drag queen, moderated the “bitching contest” between the two. Others characters in this play within the opera were semi-nude men dressed in leather, all grown men presented as altar boys, nuns, monks, and a faux-Pope complete with a humongous sexual organ that Balducci kissed instead of the Holy Father’s ring. Why add fifteen minutes of irrelevance to an already long opera that was partially cut by the conductor. As for the “humour” it generated, it was base, predictable, and overly reliant on ridiculing the Church and clergy.

The sets were appealing, especially given that the setting had been updated to the present day. They featured the major monuments of Rome: the Colosseum, Saint Peter’s Basilica, the Trevi Fountain, the Pantheon, one of Rome’s Egyptian obelisks, Trajan’s column, and more. But the result felt overcrowded, further aggravated by the tedious muses, constantly onstage. The concepts behind the muses and the monuments were valid, but alas, Strassberger’s downfall is his predilection for excess.

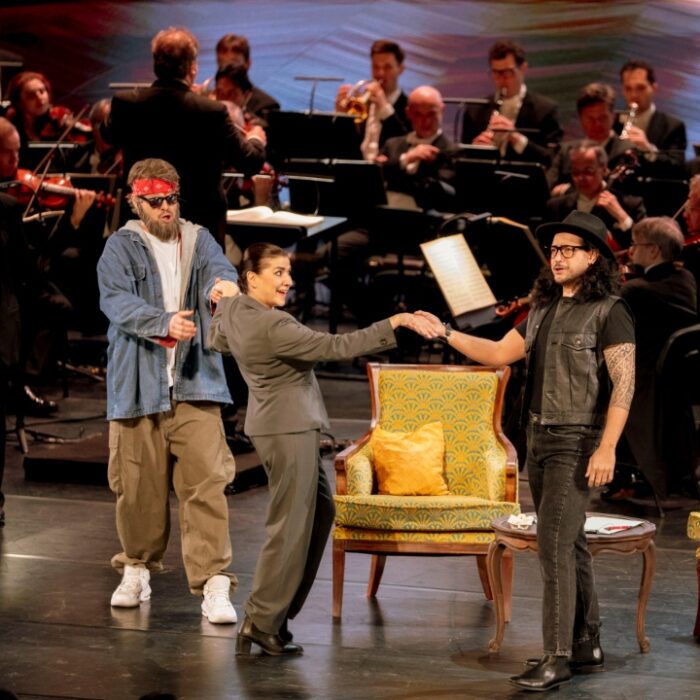

In contrast to the cumbersome staging and sets, the cast was excellent. Tenor John Osborn, the show’s uncontested star, was an ideal choice in the title role. Endowed with a brilliant lirico spinto, he was able to confront the role’s high tessitura and semi‑heroic fach. This demanding role was written for the legendary Gilbert-Louis Duprez (1806‑1896) of the “ut de poitrine“ — the operatic high C delivered from the chest. In his Act One romance, “La gloire était ma seule idole,” Osborn convincingly portrays a self-sufficient, ambitious artist’s transformation by love. He was truly affecting in his Act Two soliloquy “Seul pour lutter, seul avec mon courage… Sur les monts les plus sauvages,” in which he expresses an artist’s predicament, almost a confession by Berlioz himself, regarding the joy and burden of creativity. Though not a native French-speaker, the American tenor had impeccable diction.

Soprano Ruth Iniesta was more than adequate as Teresa, despite a noticeable vibrato. It was a performance almost as good as her Gilda in “Rigoletto” in Macerata, Italy, last August. Here, she portrayed a sympathetic Teresa, but she was no ingénue. Unfortunately, Strassberger was too busy with drag shows to bother giving direction to Iniesta to help develop her character. This resulted in making her bland, which is a real pity, as the Spanish soprano can be a very effective actress. Given Cellini’s rebellious character, it is hard to explain the artist’s attraction to a dull woman. Iniesta’s Act One “Les belles fleurs… Entre l’amour et le devoir” was slightly marred by a less-than-perfect coloratura, though her Act Two duet with Cellini, “Ah le Ciel cher époux… Quand des sommets de la montagne,” impressed all with her elegant singing and phrasing.

Baritone Jean-Sébastien Bou, known to be a fine actor, was unfortunately relegated to slapstick rather than the dry, caustic humor required to carry the disgruntled “third wheel” Fieramosca. But Bou did get some better moments, among them the Act One aria “Qui pourrait me résister?” The choice of his character’s name is not fortuitous: “Fiera mosca” is Italian for “proud housefly” — an insignificant, petty, and irritating creature.

Bass Tijl Faveyts was the Pope’s treasurer, Giacomo Balducci. He perfectly portrayed a pedantic, overwhelmed father, unable to rein in his daughter. His demeanour enhanced his awkwardness and one’s desire to irk him. Though one is not meant to cheer for this pedantic bureaucrat, there could have been some pathos given to this father. Alas, the director made him into a cardboard cutout baddie.

Mezzo-soprano Florence Losseau was an effective Ascanio, Cellini’s young apprentice. Endowed with a pleasant and warm light mezzo timbre, appropriate for travesti roles such Ascanio, Cherubino, Sesto, Idamante, and Octavian, she also had clear, perfectly understandable diction. She was impressive in Ascanio’s sole aria, Act Two’s “Tra la la la… mais qu’ai‑je donc,” one of the opera’s highlights, where she conveyed the young man’s melancholic nature and vulnerability.

Bass Ante Jerkunica was a vocally sonorous and imposing Pope Clement VII. Heard three seasons ago as Balducci in a science fiction-inspired production of this same opera in Dresden, Jerkunica’s talent is somewhat wasted on this less demanding role.

As this is Berlioz, the orchestra is more interestingly imagined than those of many other operatic composers. Other than John Osborn, the Orchestre symphonique de la Monnaie and its conductor Alain Altinoglu were this production’s undeniable stars. Berlioz, never one to follow the herd in terms of orchestration, imagined “Benvenuto Cellini” for four horns, four trumpets, cornet, trombones, and ophicleide (a brass instrument invented in Berlioz’s time that extends the keyed bugle into the lower range), as well as strings, woodwinds, and full percussion (not only timpani but also bass drum).

But not everything was perfection. Despite its pivotal importance to Berlioz’s music, the epic Act One trio, “O mon bonheur, vous que j’aime plus que ma vie” was treated as a mere afterthought. The initial segment is a melodious love duet that transforms into a trio with the addition of Fieramosca, surreptitiously present in the room. The suavely sentimental melody soon gives way to tension and mayhem when Cellini proposes elopement. When Teresa and Cellini sing “Demain soir, mardi gras” sotto voce and Fieramosca, barely able to hear, sings “Gras!” it should be one of the funniest and most refined comic moments in opera. Strassberger instead resorted to buffoonery. Conductor Alain Altinoglu also failed to highlight this moment. This trio is most likely modeled, at least dramatically, on a trio Berlioz considered to be one of the most sublime moments in opera: the Act Two trio from Rossini’s “Le Comte Ory” (1825). The idea of unwittingly introducing to a pair of lovers a third, rejected and undesired, participant, creating a trio where the lovers exchange their passion and the third party merely overhears, is both cruel and ingenious.

A successful production of “Benvenuto Cellini” should evoke the spirit of Rome, whether Renaissance or present-day (for updated productions such as this). That Strassberger opted for a phantasmagorical, imaginary, Fellini-inspired Rome may be a valid choice. However, the clutter, incessant lewdness, and base humour did not help matters. This is disappointing as it is not an insignificant work. The gratuitous ridiculing of the Church was tiresome and offensive. Some may argue that, as Cellini was an unconventional iconoclast, such a staging is in his spirit. I beg to differ. This may have been valid had the opera’s subject been the actual Cellini: depraved and criminal. But it is not. Berlioz’s Cellini is asepticized with the purpose of celebrating his creativity, not his debauchery. Consequently, the very essence of Berlioz’s work is missing in action.

Despite misgivings concerning Strassberger’s staging, it was nevertheless a memorable evening thanks to Osborn and Altinoglul. It is a pity Brussels had to wait nearly two centuries to experience Berlioz’s masterpiece, only to receive it in this vulgar staging. Berlioz and Brussels deserved better.