How Pacific Opera Project Brought Video Game Characters Into Mozart’s ‘The Magic Flute’

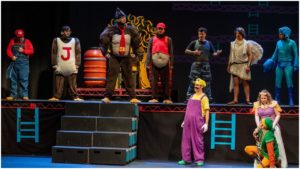

By Andres SotoThe Pacific Opera Project opened its 2019 season on March 2 with an ingenious production of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” set in classic video games from the 1980s. The fairy-tale story that premiered in Vienna in 1791 has lent itself over time to innumerable adaptations, and is often used as a way to attract children to the opera hall.

With this in mind, the producers sought to take advantage of the fairy-tales of our time (namely, video games) and devise an original and enjoyable adaptation with witty lyrics and a comical libretto in English written by Artistic Director Josh Shaw and Scott Levin (who also plays a red-hatted plumber with an Italian accent called Papageno).

The idea of producing famous masterpieces in modern and often unusual settings is not foreign to opera – it’s a way in which artistic directors constantly try to reimagine the inescapable classics of the repertoire. What makes Pacific Opera Project stand apart is from traditional modern re-interpretations of the classics is the way in which they unapologetically combine elements from pop culture and comedy to achieve an original vision. El Portal Theater in North Hollywood was filled to capacity with people of all ages, and even some of the more mature audience members who may not have grown up playing video games seemed delighted with the production.

Tamino (Andrew Livingston Geis) is portrayed as a parody of Link from The Legend of Zelda; Pamina (Alexandra Schoeny) is Zelda herself; Soroastro Kong (Andrew Potter) is the famous great ape, and the Queen of the Night (Michelle Drever) is a female version of the villain Ganondorf (the three women are Gerudos). All other characters are parodies of famous video game characters that many in attendance may have grown up playing, like Wario, Toad, Diddy Kong, and Princess Peach.

To avoid copyright infringement, the authors made a point that the opera is a parody – much like in spoofs and comedy sketch shows. The actual names of the Nintendo characters are not used during the show. In fact, much of the humor comes from this self-awareness, adding a layer of meta to the humorous libretto. For example, Papageno (the coin-collecting, mushroom-loving, overalls-wearing plumber) cannot walk to the left (much like in the original Nintendo game); Tamino pretends to “press A” to “skip” the long-winded explanations that Soroastro Kong’s minions provide, much like impatient gamers would do to avoid lengthy expositions. In one humorous bit, the main characters clumsily die after holding on to a bomb, and the clarinets play the famous death sound effect of old video games, only to immediately come back to life like video game characters.

“Of course we poke fun at that, right from the top of the show,” says Shaw about the show’s self-awareness. “All of the costumes are built from scratch (by Costume Designer Maggie Green) and I purposely avoided using 100 percent projections so the show isn’t exactly just like the games,” says Shaw, who also photo-shopped the digital projections that aid the set decorations.

Entering Nintendo’s World

The idea to use video game characters in a Mozart opera came to Shaw and Levin last summer when they were involved with a last-minute production of the Magic Flute in Illinois. A tight deadline often causes originality, so with only three days of preparation before opening night they came up with the idea to use video games to tell the story.

“It was a half-baked idea at the time,” says Shaw “but the audience still enjoyed it. Encouraged by that, we decided to do a complete rewrite for this production.”

To prepare for this 2019 premiere, Shaw and Levin took three weeks to redo the libretto and the lyrics, bouncing ideas off each other. “As you hopefully noticed, I can’t live with a non-rhyming song. Even some times when there is no rhyme scheme in the original, I have to have it.”

The new English lyrics were one of the highlights of the production, showcasing the importance that Shaw and his team give to comedy in many of POP’s recent productions. “Who would’ve thought all those years of video games actually served as character study?” says tenor Arnold Livingston Geis, whose depiction of Tamino was based on Link, the hero of the Legend of Zelda. “There’s nothing more artistically fulfilling than being a part of a new production with a committed and very talented cast and crew.

The result was a fresh take on a standard work that was unapologetic about its light-heartedness. Out of the operas in the repertoire, “Die Zauberflöte” lends itself perfectly to be depicted using the characters from the Nintendo family. It certainly does not feel more farfetched than the original 18th century story by Emanuel Schikaneder (an interesting parallelism is that Schikaneder, just like POP’s co-librettist Scott Levin, also played Papageno in the original 1791 production).

You can watch the full performance here.

No Stranger To Change

The Pacific Opera Project is no stranger to adding original and inventive takes to their productions of the classics in the opera repertoire.

For instance, in 2016 they staged The Abduction of the Seraglio as a Star-Trek episode, which was highly reviewed by the LA Times. “Our official mission statement is to provide quality opera that is innovative, affordable, and entertaining in order to build a broader audience. We typically shorten that to ‘Accessible. Affordable. Entertaining. Opera’.”

POP’s ingenious productions are an example of imaginative ways to inject life to some storylines that may be relatively dull for today’s post-modern tastes and sensibilities. Other examples of past productions include: a moving production of “Tosca” in which each act took place in different section of St. James Methodist (Tosca actually jumping off the roof at the end!); and table-seating performances of “La Bohème (Aka The Hipsters)” and “Carmen” in which the characters move around the audience, who is enjoying drinks. An upcoming joint production with Opera in the Heights of “Madama Butterfly” is going to be sung in Japanese and English. “We’ve been casting the opera for over two years and I am extremely proud to say that our entire 30 person chorus and all the Japanese roles will be sung by Japanese Americans,” confirms Shaw.

Earnest initiatives with the aim of broadening the appeal of classical opera are popping up across the country. One of them is Opera on Tap, a grassroots organization that aims to expose new audiences to opera and classical music by taking them out of the concert hall and performing it in alternative venues (such as pubs, playgrounds and schools). Another example is the Out of the Box Opera in Minnesota, which frequently incorporates Jazz, Soul, and Gospel in their concerts. These entrepreneurial enterprises may not have the budgets of the big opera companies but they make up for it with wit, creativity, and a genuine enjoyment of the art of opera.