Donizetti Opera Festival 2021 Review: L’Elisir d’Amore

Caterina Sala Delivers Star-making Performance in Donizetti’s Comedy

By Mauricio VillaThe Donizetti Opera Festival opened its opera performances with a new production of “L’Elisir d’Amore” under the baton of Music Director Riccardo Frizza. The production was a new, critical edition that included a new aria and cabaletta for Adina in Act two as well as additional music, and was played on period instruments in order to reproduce the sound of Donizetti’s time. The evening also benefited from the draw of Javier Camarena, who was making his debut at the festival.

It had all the ingredients to be the highlight of this year’s festival, but unfortunately, it was a bit disappointing.

The Star of the Night

The young soprano Caterina Sala sang the role of Adina in her Bergamo debut and was the evening’s standout. At just 21 years old, she possesses a beautiful, velvety timbre with a balanced vibrato throughout her entire tessitura. She projects wonderfully, especially as her voice rises up to the higher tessitura and her upper notes gleam.

As Adina, she was comical and extremely moving. She started with a lively version of “della crudele Isotta,” being very expressive and showing her depurated coloratura technique in the several roulades and scales going up to a high B natural. Adina is a truly lyrical role, its tessitura lies in the middle of the voice, and although she has several ascensions to high As and Bs the general writing of the role is central. Sala’s voice shined and carried from low to high, and the lower intonation of the score did not seem to affect her singing. But the highlight and big surprise of her performance was the alternative aria “Prendi: per me sei libero” from Alberto Zedda’s critical edition of the score. Although it maintains similar writing of long, sad lines with a cadenza going up to high C, the cabaletta is much brighter and with intervals to high C and high B flats that feel reminiscent of the “Quando rapito in stasi” cabaletta from “Lucia di Lammermoor.” This cabaletta sounds more suited to a bravura aria from a serious opera, rather than a buffa one. Sala sang the difficult cabaletta effortlessly and with legato ascensions to high Cs, a direct attack on a D flat on the first verse, and impeccable trills on the cadenza between verses. She added subtle variations on the repetition of the cabaletta, mostly jumps in staccato to high notes, and an explosive, thunderous E flat to conclude the piece.

With such an incredible performance, Sala promises to have a huge career in the coming years.

Uneven Singing

Star tenor Javier Camarena struggled as Nemorino. The score is written for the middle of the tenor’s register, whereas Camarena’s career has been focused on operatic writing in his upper reaches. The use of period instruments and tuning of the orchestra to 432hz—which is lower than the common tuning of 440hz—did little to help. Even though Camarena’s middle register has widened, and his voice has gained security in the middle range, he comes from a lirico-leggero vocalitá where the scores are written constantly above the passagio zone, plus the ascension to extreme high notes, while Nemorino’s part is written mostly inside the stave and with rare ascensions to high A. His cavatina aria “Quanto é bella” sounded muffled and weak, as the tenor tried to lighten the sound when most of the lines appear down around low E. Even though his legato singing was mesmerizing, the voice did not shine as it used to. This problem was noticeable throughout the first act, where the tenor did hardly any dynamics and diminuendos but tried to keep the sound light and secure. His diminuendo in the line “che non sa dir, un poter” was exquisite, but in general, he sang forte. He still had memorable moments, such as the lamenting “Oh Adina credimi…” sang with despair in an exquisite mezza voce.

It seems that his voice had settled by the second act. His duet with Belcore sounded more secure, even if he still sounded more like a baritone than a tenor. He sang again “Una furtiva lagrima” without his usual mezza voce and piannissimi, which displayed once more that he needed to secure the sound because he was not comfortable with the tessitura. But the end of the aria was breathtaking. The tenor kept the silences between lines in “Si puó morir” long, sustaining an atmosphere of tension and expectation that sounded extremely expressive as a result. The tenor ended the opera going up to high B flat alongside the soprano, which is something not written in the score and which was climactic.

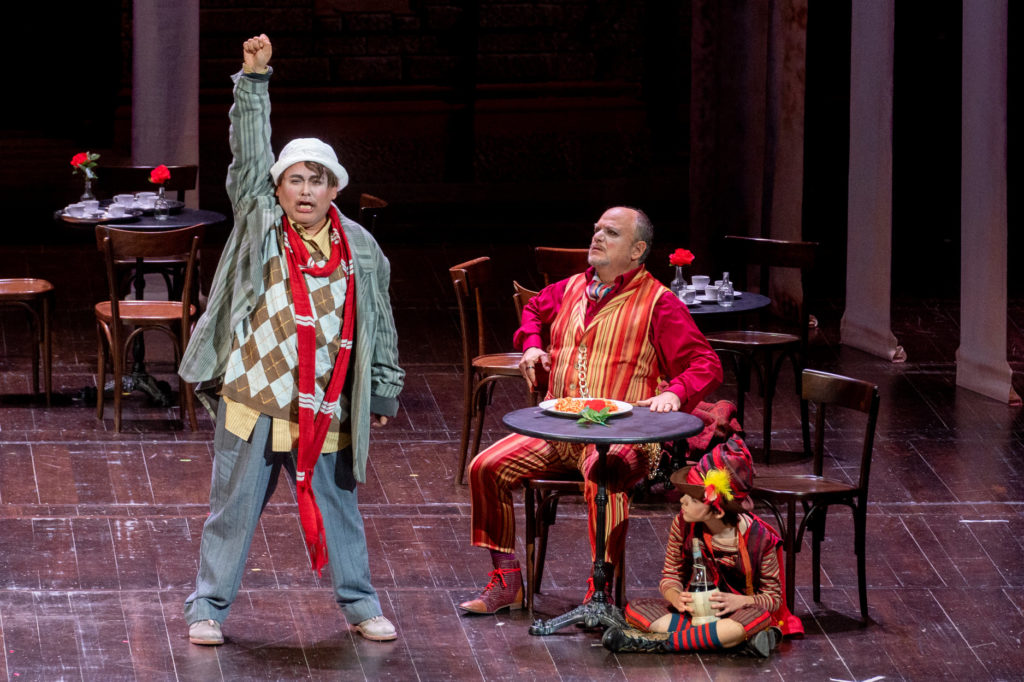

To make matters worse, the oversized clothes and sailor’s hat he was wearing, along with an exaggerated clownish interpretation, made him draw focus from the rest of the cast who performed with measure and truth. His characterization was, as a result, exaggerated and over the top. If the audience does not laugh at Nemorino’s part something is wrong, and the Bergamo audience was silent and still throughout the performance.

Baritone Roberto Frontali’s casting as Dulcamara was a bit of a surprise, as the role is written for a basso-buffo. As a result, Dulcamara’s low tessitura seemed uncomfortable for Fronatli’s voice. It also sounded distant and small throughout the performance. Nonetheless, the baritone’s singing was refined and lyrical. He avoided any Parlato singing typically done in this role. For example, “Udite, udite o rustici” was a lesson in bel canto, as he sang with long, fluid legato lines and a wide array of dynamics.

Florian Sempey portrayed Belcore and while his timbre sounded warm and natural, the sound was guttural and lacked good projection. He has a good handle on the bel canto style and his phrases are fluid and long, but like some of his colleagues, the role proved to be too low for his voice to properly shine. His acting, however, was wonderful and he created a funny and believable character.

The new production was directed by Frederic Wake-Walker, who set the opera in Bergamo itself. The action took place in front of a painted canvas of the Teatro Donizetti and some of the canvas arches that were lowered down for certain scenes were reminiscent of Bergamo’s Piazza Vecchia. The costumes looked like they came from the 1920s but were not specific. An interesting element in the production was that children doubled the characters of Adina, Nemorino, Belcore, and Dulcamara. The staging was simply too correct, however, and did not bring anything new to the piece itself, appearing very routine. The interpretation surrounding the performance, however, was anything but routine.

Thirty minutes before the performance began there was acting outside the theatre, introducing the characters, and playing with the puppet’s theatre that would become relevant later on, during the barcarolle in the second act. Front house staff distributed small colored flags with a verse from the second act opening chorus written on them to the audience as they entered the theatre. A master of ceremonies taught the audience the rhythm and melody of this written verse, rehearsing it and making the audience sing it. This was all in preparation for when the audience sang alongside the chorus at the beginning of Act two. It was a very clever way to make the opera more accessible to the audience.

The music director of Donizetti’s festival presented a critical, uncut version of the score. It was probably the first time since Donizetti’s period that the opera was played unbridged. The Orchestra Gli Originali played with original, period instruments, not reproductions of antique instruments, tuned in the aforementioned 432hz. Riccardo Frizza tried to recreate the original Donizetti sound as much as possible. Although this choice might be welcome for a musical purist in the audience, the period instruments sounded weak and strained. We are used to a clearer, purer sound from today’s instruments. At certain points, it sounded as if a chamber orchestra were playing as opposed to a full one, and the lower tuning made the music less bright and cheerful. There were some brilliant moments from the music as well, however: Frizza’s wink when playing Wagner’s “Tristan chord” on the pianoforte when Isolde’s love elixir was mentioned in recitatives was very clever.

Over this was a modest production with a stellar cast of singers dominated by the young soprano Caterina Sala, in a questionable attempt to deliver the opera as it was played in Donizetti’s time.