Tulsa Opera 2019-20 Review: Carmen

Sarah Mesko Rises To The Top In Disappointing Take On Bizet’s Masterpiece

By Freddy DominguezIf stuffy audiences at the Opéra-Comique first attacked George Bizet’s “Carmen” for its offensive content, today the opera runs the risk of seeming antiquated.

Much of the music might get your toes tapping, but over-exposure risks making the most popular tunes seem trite or even parodic. Today’s audiences might not appreciate the orientalist take on Spanish culture that was so prevalent in nineteenth century France — Spain as a mysterious, not quite European land of bullfights, gypsies, and castanets. Most importantly, many American audiences might not embrace the opera’s gender politics with its emphasis on the dichotomous whore/saint perspective on womanhood.

A successful and “relevant” mounting of “Carmen”– and of so much classic opera– depends on a dramatic pulse that overcomes specific narratives allowing listeners/viewers to explore the emotional depths and the dramatic dilemmas that survive unscathed by time and shifting cultural perspectives.

I attended Tulsa’s production of “Carmen” with high hopes, especially since not long ago a previous production there of Bizet’s other famous orientalist opera “Les pêcheurs de perles” was such a resounding success.

Unfortunately, despite a very talented cast, this “Carmen” fizzled.

Intensity Matters

The dramatic limits of this production began in the pit.

Roberto Kalb elicited some beautiful playing from the Tulsa Opera Orchestra in moments of serenity and in stretches of willowy music, including the famous Act three prelude and in the accompaniment to Micaëla’s aria in that same act. More often than not, however, his was a limp reading of the score. There didn’t seem to be enough of the musical expansion and compression, the harnessing of tension that makes the opera’s musical outbursts exciting.

This dynamic was evident from the start. In the prelude, the pause before the final section (the all-important introduction of Carmen’s incantatory theme) is marked “G.P.” (General Pause) in the score I use and is meant to set up the striking, sonorous, ominous music to come. Kalb’s pause was minuscule. When the theme began, the orchestra seemed oddly monochromatic. The brass blared, but the underpinning tension often elicited by the strings was muted.

A similar glitch crept into the prelude to Don José’s aria, “La fleur que tu m’avais jetée” lacked the requisite throbbing that prepares the blooming effect of the tenor’s first line. A static start to Act two failed to create the right pace to end “Les tringles des sistres tintaient” with the exciting dervish-like furor it merits and the entr’acte leading to Act four did not “pop” in the way the fun flamenco-style stretch might.

The orchestra did sway with Carmen in her sensuous Habanera and bounced with Escamillo in a delightful Toreador Aria, but overall the performance lacked bite.

Bad Boy(s)?

The main disappointment of the night involved Adam Smith’s Don José. Smith is a true tenor in a golden-age tradition with a powerful clarion sound blessed with a warm center and steely edge. If toward the end of performance there was a touch of hoarseness– I worried he might have been pushing his voice too much– he was undoubtedly an audience favorite. Apart from vigorous applause, he received the most interesting audience response during curtain calls: a few rows down I noticed a young man bowing in recognition of Smith’s performance.

The problem was mainly about interpretation. The program notes quote the stage-director Harry Silverstein saying that he believes “the bad person in the opera would be Don José! He’s definitely a bad boy.” This is a worthy reading that at once takes into account what we know of the character’s history of violence from the source text, Prospér Merimée’s novella “Carmen,” and from the perspective of modern sensibilities that might tend to soften the strong dichotomy between Carmen as a guilty Eve and Don José as an exculpable Adam. For this to work within the context of the drama, however, we have to develop a sense that there are points at which and reasons why Don José falls, and falls hard, for Carmen. Smith’s interpretation of the role does play up gruffness and unbridled virility, but at the expense of a connection to Carmen.

His “Flower Aria” exemplifies the limitations of his performance. While the singing, the sheer force of the voice, is enticing, he did not convey the struggles of a man confronted by passion for a woman that he might well know is bad for him. Smith’s reading was monochromatic in its tone and it blew over the twists and turns, the ebbs and flows of the music.

The lack of connection with Carmen ultimately undermined what could have been Smith’s finest moment. In Act four he offered his finest acting of the night as a dejected, depressed Don José on the edge of lifelessness. His almost catatonic demeanor created a strong contrast with the pangs of ultimately lethal feeling that leads him to stab Carmen. But by this point, the previous three acts had taken their toll and the effect was unfortunately diminished.

Apart from the Toreador Song, the role of Escamillo is scantily drawn and mostly thankless, but Alexander Birch Elliott made the most of it. Elliott is a serious talent with a voice that is sonorous and solid, virile and supple. In his first fleeting encounter with Carmen, he seemed genuinely and almost spontaneously smitten. With this suggestion of germinal interest and his magnetic swagger, Carmen’s reciprocal infatuation gained credibility.

Tough Women

Sarah Mesko’s Carmen reminded me of Marylin Horne’s take as captured in the 70’s recording led by Leonard Bernstein: earthy, confident, and direct. This was a Carmen without many secrets–what her lovers saw was what they got. What the audience heard was an exciting mezzo gifted with a generous tone marked by warmth and richness in its middle and lower parts and a silvery sheen as it climbs upward.

Mesko delivered the goods in her taunting and seductive Habanera and Seguidilla, but most impressive was her effectively stoic take on the tarot-reading scene. This music often lures performers toward bathos, but Bizet astutely and intentionally tried to avoid this by indicating temperance at various points. Mesko’s approach was measured and extraordinarily sophisticated.

Only once was there a detectable lapse in her singing. The crucial moment after Don José declares his love for her is tricky because, although Bizet refused to allow a pause for applause, audiences inevitably do applaud, challenging the effectiveness of what is supposed to be Carmen’s near immediate response: “Non, tu ne m’aimes pas.” This line is meant to reject and coax at once and so it requires dramatic emphasis, which Mesko did not give it.

Mesko is a good singing actress. Of the whole cast, she seemed to be the most comfortable and most effective in her use of French for the dialogue and throughout she managed the challenge of singing and dancing– with very elegant flamenco-style snapping. When seated she weighed her body down and manipulated her legs to maximize her presence and suggest raunchiness without vulgarity. At other times she seemed to slither as she moved across the stage.

When she was not the center of attention, however, she seemed to be swallowed by her surroundings. I suspect this was in part because of the overstuffed stage, but also because of the dreary attire she was given.

As Micaëla , Colleen Daly made excellent use of a voice that is agile and elastic without ever losing its lusciously honeyed hue. Her performance was true to the role’s girlishness, but she was no wallflower. Her take showed the grit Micaëla had in trying to save Don José from his fate.

A Deep Cast Lost in Space

The Tulsa Opera boasts consistently on-point performances from its choral ensembles. The group made some riveting sounds throughout, especially in Act four. Special mention must be made of the Tulsa Opera Youth Chorus that gave — as it often does– a pitch-perfect, well-articulated, and energetic performance.

The company singers were all great in their secondary roles, especially Alice Chung as Mercédès. She brought some needed levity to her scenes and a gorgeous, plush sound as well.

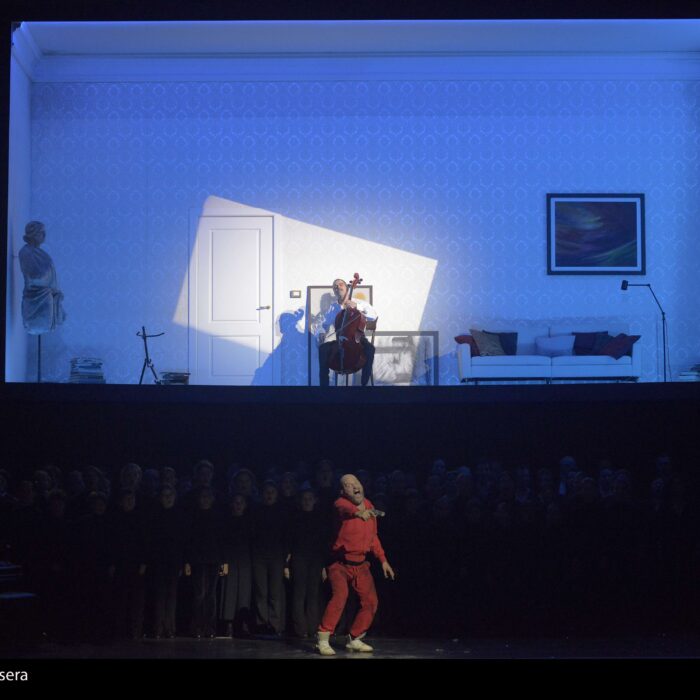

The sets, originally for The Atlanta Opera by Allen Charles Klein, didn’t help the drama.

The action took place between two arched facades of stone and plaster in the charming style of nineteenth century Seville, but the space was unfortunately limited. This likely gave the stage director relatively few options but to crowd performers together creating an often confusing clutter.

The two buildings were so imposing that each scene change lacked clarity and ultimately proved unconvincing; there was an insufficient sense of place. To overcome such an impediment, the performers themselves bore the total burden for the show’s success.

And so this deeply talented cast of singers and players amounted to less than the worth of its constituent parts. A shame, but also a reminder that popular classics such as “Carmen” are not inherent successes despite their apparent genius.