Teatro alla Scala 2023-24 Review: Don Carlo

An Unforgettable Cast led by Francesco Meli, Anna Netrebko & Elīna Garanča

By Francisco Salazar(Credit: Brescia e Amisano ©Teatro alla Scala)

The Teatro alla Scala’s opening night production is always a major event. But this year’s “Don Carlo” had particular high expectations to fulfill. The major reason for this was undoubtedly the A-list cast, headlined by two of the world’s most famous divas Anna Netrebko and Elīna Garanča. But they were also flanked by an impressive band of Italian male singers, including Francesco Meli, Luca Salsi, and the legendary bass Michele Pertusi.

And the result on the third night of the run, on Dec. 13, 2023, was extraordinary. At least musically it proved a demonstration of the brilliance of the work and its interpreters in bringing it to life.

The production was another matter.

The Problematic Fourth

One can argue that Verdi’s “Otello” and “Falstaff” are the composer’s most pristine masterworks, the exemplars of his genius as an artist and craftsman. With the former, he made an artistic statement in exploring the troubled waters that his beloved Italian art form needed to navigate as it moved forward. Through the murder of the bel canto-singing Desdemona and victory of the less lyrical Iago, the tragedy of “Otello” seemingly looks back at what’s been lost and sacrificed as modern opera moved into a new direction. Meanwhile, “Falstaff” is an explosion of creativity and bravura from an artist that is just having the time of his life. The final fugue, some speculate, was Verdi getting some vengeance on the Conservatory of Milan that rejected him in his youth for not writing a proper fugue (“Falstaff” had its world premiere performance at La Scala).

But “Don Carlo” is arguably his most compelling work, mainly because it presents a unique challenge for any director that takes it on – mainly that “Don Carlo” has multiple versions and in recent practice, conductors and directors can seemingly pick and choose how to compile the work to suit their dramatic needs. In an era where directors seemingly change plots of operas, fighting against the libretti in a search for new meaning, “Don Carlo” is a work that literally allows for that kind of textual play and subsequent interpretation.

And given La Scala and its music director’s propensity for putting on unique versions of classic operas, one might have expected something more adventurous in that department.

The ultimate choice was the four Act version, often known as the Milan version, though Verdi seemingly made a final statement with the Modena version from 1886 that restores the first Act. This, in my view, is the finest version combining not only the best music from Verdi’s four-act iteration, but also preserving the opera’s dramatic cohesion.

The problem with four acts comes down to balance. The opera opens on lost-love, but also emphasizes all the political scheming at play that drives Elisabetta and the titular hero apart. Without that scene, we can never truly feel the weight of Carlo and Elisabetta’s loss. It is manufactured in “Io lo perduta,” the epitome of the “telling instead of showing” problem of storytelling. Act one lets every other event fall with greater impact, whether that be the rivalry between father and son, the pain behind Filippo’s aria and our own emotional conflict with the character, and even Filippo’s confrontation with Elisabetta. That opening act is the opera’s thesis and without it, not only do we miss a bunch of the dramatic weight, but the opera might as well not be called “Don Carlo.”

But this is a point that has likely been talked to death for over a century since the work’s inception. What matters in terms of modern theatrical practice is how this imbalance can be further accentuated in a production. Willy Decker’s take on the four act version actually gave Don Carlo greater focus, emphasizing his historic mental illness and the patriarchal structures limiting him and others in the work.

But in Lluis Pasqual’s production, the central character essentially fades into the background of his own story. And this comes down to the design of the production and his direction of it.

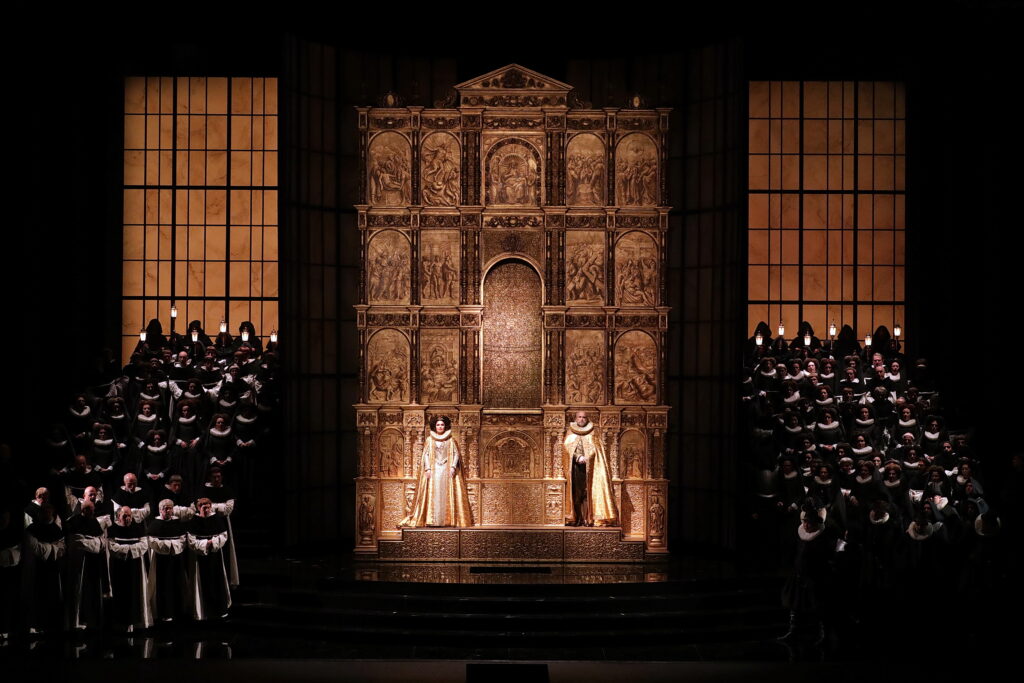

The production’s design is simple and, though elegant might not be the right term, it’s proper. A central rounded column dominates the center, rotating to open up and reveal different set configurations (it also creaks like crazy, distracting from some major musical moments. The fact that its changes are so slow, doesn’t help matters). In Act one, we get the inside of the cloister. It then turns into a courtyard. Later on, it’s the inside of a church and Filippo’s bedroom (both featuring two benches). Later it becomes the inside of the prison and then eventually we get the exterior of the monastery with a potent statue of Carlo V. The most impressive use of that central structure comes during the Auto-da-fé where we get a massive golden wall. When the King and Queen stand in front of it and the Inquisitor comes into the center, we get a stage-like recreation of a medieval painting, striking not only for its characteristic flat look and golden colors, but also its clear religious iconography and meaning of the church standing over the crown. Then flames erupt from the floor, clinching the spectacle.

It also closes up and allows for some lighting effects to produce other settings like the moon in the garden or the cross emblazoned on it during Filippo’s aria. All the while, gates, and walls come down on the sides to support these set configurations.

It’s ironic that the most striking moment of the entire production is a static one, because that’s also the production’s downfall. Everything feels stuck in place, including the performers (entrances were always very awkward, especially when gates had to be opened; Don Carlo’s opening “Io lo perduta” opens with agitated music, but tenor Francesco Meli walked on slowly and seemed to take too long to get that gate open, creating a disconnecting effect with the music) and the now cliché use of black for this opera in nearly any production you can think of. Yes, “Don Carlo” is a dark, depressing world. Perhaps the most pessimistic of Verdi’s career, ending on a cliffhanger that no one can comprehend, but with music that doesn’t give us any hope (especially the final thunderous finale Verdi left). But that doesn’t mean you always need to use black to get that point across. It just feels like it is stating the obvious, which extends to what Pasqual has to say about the work – nothing new.

Some might defend this traditionalist stance as, he’s respecting the music and the text. And to be fair, it’s a pragmatic production and there are some very good ideas here (the start of Act, which we will get to later, as well as the murder of the “heretics” at the start of the Auto-da-fé). But the problem with these productions is that it places all the onus on the performers to bring nuance and ideas to the production essentially devoid of them. With a Grade-A cast, like the one currently taking the stage in this production, their brilliance alone will carry the day. With anything less than that, because of the clear lack of direction, this might as well be a concert performance.

Costumes are elegant, period-relevant and generally cohere to the black aesthetic, though, they don’t really reveal much about the character. It also didn’t help that Elisabetta’s robes during the third act confrontation with Filippo, a green coat over a white dress, looked a lot like what she wore in David McVicar’s production of “Il Trovatore.” Leonora and Elisabetta might both be heroines in a Verdi opera set in Spain, but they don’t share the same social circumstances and should definitely not be calling back to one another. One might surmise that Pasqual and company are assuming audiences have not seen that “Trovatore” but given the fact that it’s Anna Netrebko in that wardrobe and the internet exists, this felt a bit like a questionable oversight on the part of the production team.

The Queen

In the role of Elisabetta, Anna Netrebko is singing her first performances of the role in Western Europe. The soprano has been quoted as saying it is the most challenging role she has sung in her entire repertoire and has noted that the vocal line is difficult to understand as it is low, heavy, and light. She also noted that the role is one where she must keep her emotions hidden and subtle. For all those who have followed Netrebko’s career, the soprano’s stage presence is charismatic, magnetic, and far from subtle. And this evening one could say her Elisabetta was full of dimension.

When Netrebko first entered the stage, you could sense her queen’s unhappiness through her resonant chest voice, emphasizing the nostalgic quality. Her lines “Una canzon qui lieta risuono” were delivered with such sadness and conflict but Netrebko kept her emotions contained in her first interactions on stage. That conflict only built in the ensuing duet with Carlo. Here her voice slowly grew in volume as she confronted Meli’s Carlo. Her first lines “Prence, se vuol Filippo Udire” were given a regal presence only to slowly explode in turmoil in “Perché, Perché accuser ul cor l’indifferenza.” The higher notes gained resonance and power throughout this passage. And then as she sang the parlando lines “Giusto ciel, la vita gia manca,” one sensed Netrebko’s queen giving into Meli’s Carlo. The voice softened and the soprano gave into the passion of the moment, singing with soft floated notes on “Bonta celeste deh!” and an emphasis on her chest notes during “Aihme! il dolor l’uccide.” She caressed each line during this middle section and Meli and Netrebko’s voices melded into one. But that quickly dissipated in her “Oh! Carlo!” as one sensed the terror in this Elisabetta and the following lines “Compi l’opra, a svenar corri il padre,” the soprano brought out the full force of her imposing middle voice. Her closing “Signor! Signor!” was filled with an intensity that allowed one to sense the queen tearing up.

In her first aria, “Non pianger, mia compagna,” Netrebko displayed a gorgeous piannissimo on the lines “ritorna al natio, coi voti del mio cor.” She took one of the phrases with one breath as she crescendoed to a forte sound, floating the lines with delicacy and care.

One of the best scenes of the evening was Elisabetta’s confrontation with Pertusi’s Filippo. Here, Netrebko’s Elisabetta was nothing short of defiant. Her “Giustizia!” while starting a bit pitchy was sung with potency. Then she quieted down as she was forced to confess to having Carlo’s picture in her jewel box. In the following phrase, “Ben lo Sapete,” Netrebko’s voice took on a hard edge and she delivered accented lines while retaining a firm legato. As the line continued, her voice grew with defiance until she reached the final “E chi m’oltraggia e il re” and produced an explosive sound that filled the scene with even more tension.

In Act four, Netrebko sang what perhaps was her standout moment of the evening “Tu che le vanità.” Her opening lines were filled with intensity in a declamatory way before coming down to a piannissimo on “piangi sul mio,” the legato phrase floated with delicacy and allowing the listener a window into Elisabetta’s sorrows and regret. In the B section of the aria, Netrebko moved throughout the stage as she reminisced about Fountainbleu and her love for Carlo. Her phrasing emphasized Elisabetta’s conflict between her duty to the throne and her personal passion. She had moments where she floated phrases with ease, but when she sang the lines “Addio, verd’anni, ancor!” the soprano pushed the tempo forward with a gutsy chest voice, ending the phrase with a poignant “la pace dell’avel.” Her repetition of the A section was even more intense, the soprano filling the hall with what one could only describe as a titanic sound. But in the closing lines, she went back to her lyrical middle voice and ended the aria with sublime gentleness. She was rewarded with an extended and well-deserved ovation.

Contrasting with the first duet with Carlo, Netrebko showcased a very different character in “Ma lassù ci vedremo.” She opened the duet with a strong tone that equaled Meli’s heroic vocalità, especially during “Si, l’eorismo e questo e la sua sacra fiamma;” during this section her high notes were particularly striking in their flexibility and vibrancy. Then in the final portion of the duet, her voice turned to a gentle tone, emphasizing the richness of Verdi’s bel canto writing, allowing the listener to surrender to the music.

She ended the evening with a powerful B on “Oh Ciel!” holding the note over the crescendoing orchestra. She didn’t quite pull a Montserrat Caballé (extending the note over the entire orchestral coda), but there was a moment where the force of her delivery and how it rode over the orchestra made me wonder if she might just try it. It wasn’t necessary, but the impact was quite enthralling.

The Princess

As Netrebko’s rival Elīna Garanča sang the role of Eboli. One cannot deny the sheer chemistry that both Netrebko and Garanča have on stage and while they only share one major scene (albeit a short one), one could say that that moment was one of the most riveting of the entire evening. As Garanča sang her lines “Pieta! Perdon!..Per la rea che si penate,” Netrebko stood above her in a regal stance only becoming weakened by the confession of Eboli’s love. The ensuing response as Eboli confessed her love for Carlo, Netrebko sang the lines “Voi l’amaste” with empathy, and then the “Sorgete” was given commanding force. But Garanča’s “No! Pieta di Me! un altra colpa” saw her voice gain more desperation and in the response, “Ancor,” Netrebko held the line with chilling power. Garanča’s confession was sung with silence and unease, each line obtaining a disconnected effect and ending with a hushed and chilling “commesso.” Netrebko delivered “Rendemtemi la croce!” with an imposing sound that emphasized the soprano’s pain and dominance over Eboli.

Then came a heartbreaking and showstopping “O Don Fatale.” Garanča opened the aria with a resonant wave of sound, highlighting her despair. As she repeated “ti maledico,” her voice continued to gain power and force. It was cataclysmic in its impact, the desperation soaring higher and higher. She eventually came down to her lower register on “o mia beltà,” the grit in her chest voice taking over, expressing the torment and contempt. In the middle section, “O mia regina,” the mezzo sang with a pure bel canto sound, displaying some of the most elegant and gorgeous legato singing of the entire evening. It was heartbreaking to watch as Garanča, lying on the floor, caressed each line with warmth. In the final coda “Oh ciel! E Carlo! a morte domain,” the mezzo’s voice regained a metallic brightness and she once again built up momentum to a truly cathartic high B5 to cap the aria.

Garanča nailed the tragic dimension of Eboli so perfectly because of the journey she charted to get there. When she first entered the scene in Act one, she had a striking and imposing personality that was on full display in the “Nel giardin del bello.” This aria is generally one of the most tense experiences one has in a production of “Don Carlo.” It’s difficult and mezzos that are built for dramatic “O don fatale” aren’t necessarily the right voices for the bel canto challenges of this aria. As such, many labor through it while others conquer the challenges but never quite seem free from the effort of it all. Garanča sounded like she was having fun out there. The sound was effortless and her portamenti on the repeated high note jumps are phrasing choices I personally have never heard, expressing the sheer joy and exuberance of the moment. She sang with clean coloratura and precise portamento as she climbed to her higher register, each note bright and clean. In the second verse, the mezzo walked to center stage, delivering more accented lines, particularly in her lower chest voice. When she went up to the high notes, she held some out, demonstrating her ability to float the notes. She embellished each line with ease and as the aria climaxed she held out her final high note with power. Moreover, Garanča melded her voice beautifully with Elisa Verzier during “Tessete i veli.”

In the trio with Elisabetta and Rodrigo, Garanča displayed a beautiful chest voice, that while sometimes thinned out, was still resonant. Throughout this scene, she moved with intrigue and with a seductive force to see what Salsi’s Rodrigo was saying to Netrebko’s Elisabetta. She ended the scene with a hopeful smile as she walked offstage. Then in the Act two trio, Garanča’s tone brightened upon seeing Meli’s Don Carlo. Her lines “un tanto amor e gioia a me sprema” were filled with a gleaming blaze that crescendoed to the “Oh! Gioia Suprema!” But that joy quickly vanished as Garanča’s voice darkened on the lines “Ahime! Qual mai pensiero.” Here, the mezzo’s voice had a hesitant and disappointed feel, and as she confronted both Rodrigo and Carlo in the trio, her voice grew in size and defiance. Her high notes were distinct among the ensemble, if sometimes sharp, and her coloratura runs were delivered with flexibility that represented the manipulative quality of Eboli. Finally, as she sang “Trema per te falso figluolo,” Garanča blasted her sound into the space, demonstrating the control she had over the scene. There was even a moment when Salsi threatened her with a knife and Garanča defiantly brought it closer to her, challenging him to go through with it.

An interesting part of this production was that audiences got to see Eboli alone with the King before Fillipo’s big aria at the start of Act three. Here the mezzo emphasized the loneliness in the character as Pertusi’s king left her behind after getting what he wanted from her. In the political battle between the men, her role was perfectly embodied here – she was little more than a tool for them. Contrasted with our last interaction with her, the potent garden scene where she had all the power, this brief moment, was a striking moment that further emphasized Eboli’s tragedy. It was one of the few moments where Pasqual’s direction really added to the overall story.

The Leading Man

In the title role, Francesco Meli started the evening slowly as his voice took its time to warm up and even then there was some strain in the upper reaches. He missed the high B in the Auto-da-fé scene and he had an intonation issue on a high note in the final duet with Elisabetta. But these little mishaps did not take away from Meli’s musicality and elegance in phrasing a line. Nor did it take away from the intensity of his singing. His “Io l’ho perduta!” saw the tenor open with a desperate forte only to quickly soften the sound as he caressed the phrase “Io la vidi e il suo sorriso.” He was able to diminuendo throughout with such immaculate flexibility and as he ended the aria he crescendoed to an agitated forte on “Io l’ho perduta,” only to wither away to a sublime piano.

In the duet with Luca Salsi, Meli had a couple of hesitant entrances as his voice seemed to constrict, especially in the declamatory moments. And at the height of the duet, he faded a bit, seemingly relying on Salsi to carry them to the end. That being said, one could always sense the tenor’s character stricken with grief throughout the recitatives. In “Dio che nell’alma infondere,” Meli’s voice obtained a lighter lyrical character that blossomed into the higher tessitura. In the second repeat of the melody, he sang with a pure piano dynamic that melded well with Salsi’s stronger baritone.

In his two duets with Netrebko, Meli demonstrated incredible chemistry with the soprano and showed two very contrasting characters. In the Act one duet, “Io Vengo a domandar razia alla mia regina,” Meli consistently grew agitated in the first half, especially on the lines “Tal nome no” and in “Infelice! Puo non reggo!.” In these bars, his tenor obtained a more disconnected line, the disquieting character growing more intense in “Insan! Piansi, pregai nel mio deliriro.” During “perduto ben, mio sol tesor,” Meli lay down on the floor, delivering passionate bel canto phrasing that matched Netrebko’s darker but floated piano lines. That ethereal quality in their voices was eventually interrupted as the agitation in Meli’s voice returned during “Sotto il mio pie si dischiuda la terra.” The Italian tenor produced a forte sound that emphasized the confrontational character and ended the duet with a sustained “Ah! maledetto io son!” that seemed to last for a long moment as he ran off.

Meanwhile, in the final duet, Meli’s singing was more heroic, especially during the “A lui n’andro beato” and “Si, con la voce tua quella gente m’apella.” His higher register strengthened with an ardent timbre. But then during the “Ma lassù ci vedremo in un mondo migliore,” Meli’s voice took on a more melancholic and nostalgic timbre and he sang with delicacy and elegance, matching Netrebko’s floated lines. This was one of the highlights of his evening as he moved through the lines with such flexibility and ease.

Meli also had some outstanding moments in the Act two trio with Eboli and Rodrigo as he expressed the ardor and passion for Elisabetta in the opening of the act in “Sei tu Sei tu.” He was also impressive in the Auto-da-fé scene where for the first time in the evening one sensed the heroic quality of his character, bringing the full force of his tenor.

The Friend

Luca Salsi brought a force to his Rodrigo that at many times dominated each scene with his striking baritone. In his opening duet with Carlo, he brought a booming sound that contrasted with Meli’s more lyrical timbre and in many ways emphasized the heroic quality of this Rodrigo.

Then in his ensemble solo “Carlo, ch’e sol il nostro amore,” there was a smoothness to his voice that connected gorgeously with each phrase. It was a contrast to Netrebko and Garanča’s more parlando phrases. Throughout the solo, Salsi also embellished in the second repetition holding some of his phrases longer and giving his voice a more noble timbre.

But his big moment of the evening was his duet with Pertusi at the close of Act one. His “O Signor, di Fiandra” was delivered with impeccable diction and staccato lines that emphasized Rodrigo’s passion. His baritone gained more force as the passage continued, until he got to “Ah! Sia benedetto Iddio,” which he interpreted with passionate legato lines and crystalline upper range. “Orrenda, orrenda pace!” brought out grittiness in Salsi’s voice and as he turned toward Pertusi’s king, there was a tension-filled silence that was among the best theatrical moments of the evening. It went on for a while as they stared at each other, Pertusi stoic while Salsi in panic. He looked down, but then regained his courage and looked back up at the king to utter, in light and pained voice, “O Re! non abbia mai di voi l’istoria a dir: ei fu Neron!” And then in “Quest’e la pace che voi date al mondo?,” Salsi brought back his booming timbre, but one could hear a more desperate cry out to the king that ended in a heroic, extended high note on “La libertà.”

In the Act two trio, Salsi was also impressive in his demeanor facing off against Garanča with his sonorous voice proving a good match for the mezzo’s strong high notes. This scene felt like the battle between two vocal titans.

But in his most famous aria, “Per me giunto,” Salsi struggled, his intonation flat for much of the aria as he attempted to sing in a more restrained tone. It was tough to listen to, especially given the commitment that was so evident in his legato phrasing and the intensity throughout the aria. Salsi is one of the great Italian baritones and few know how to deliver a phrase of Verdi singing quite like he does. He just understands that flow. So to hear him struggle with the intonation in this aria was unfortunate. However, he bounced back in his second aria, “Io morro, ma lieto in core,” delivering a passionate and immaculate interpretation.

The King

Michele Pertusi has become one of the most sought-after Fillipo interpreters, singing the role throughout Italy to great acclaim. And on this evening the bass demonstrated why.

Pertusi entered with great presence in his opening lines, “Perché sola la regina.” From this entrance, you knew he was a force to be reckoned with and for the first two acts of the opera, he was stoic and rigid in his demeanor. His bass was forceful and sonorous, especially in the duet with Rodrigo. While Salsi was all about passion, Pertusi’s voice never quivered against Salsi’s and instead, you could sense many hidden sentiments that would only be revealed in Act three during his big aria. The same could be said about his Act two confrontation during the Auto-da-fé. Pertusi maintained a regal sound and appearance as he sang “A dio vi foste infidi” and even as he confronted Carlo “Che? nessuno.” Only towards the declamatory lines “Disarmato ei sia” could you sense a little desperation setting in.

And that was confirmed in his “Ella giammai m’amo.” His opening lines were sung with a restrained but fragile sound that remained contained. His “Amor per me non ha!” during the the first A section was sung with an introspective timbre, not quite ready to break free. In the B section of the aria, Pertusi’s bass became filled with desperation as he sang the lines “Dormiro sol nel manto mio regal.” Here the Italian bass showcased a gorgeous legato line filled with pain that grew in agony as the introspection built towards outward emotion, especially on “a desse il poter di leggere nei cor!” These lines were interpreted with more accented phrasing that crescendoed to an explosive forte. However, Pertusi decrescendoed to a piano sound for the recapitulation of “Ella giammai m’amo,” before finally breaking loose emotionally and delivering the final “Ella giammai m’amo” with the most potent sound he delivered the entire night. The architecture of the musical experience was second to none and the catharsis that arrived was an all-encompassing expression of desperation and loneliness. I still have chills remembering the moment.

In his subsequent scene with the Grand Inquisitor, one could sense that the powerful King from the first two acts was becoming even weaker and desperate. In a way, Pertusi’s king was reminiscent of Salsi’s Rodrigo in his Act one duet. Here Pertusi’s bass was no longer firm and booming. Instead, it had a more plaintive quality that contrasted beautifully with his counterpart Jongmin Park, whose voice felt like a tidal wave of imposing sound. The scene was filled with ferocity and incredible tension that would only continued throughout the act.

And speaking of tension, his subsequent scene with Netrebko saw Pertusi all the more weakened. Here, Pertusi’s King brought back that implacable force from the first Act, but you could sense that this king was already distraught as he sang the lines “Il Ritratto di Carlo!” His three repetitions continuously obtained a more anguished sound that crescendoed into the declamatory manner in which he recited the lines “Ah! La pieta d’adulter consorte!” In this scene, Pertusi’s king became more violent as he took Netrebko by the neck almost as if to choke her. This was a king who had lost all power. And that was most evident in the quartet as he sang “Ah! sii maledetto, sospetto fatale” where his vocal line was full of remorse.

Fantastic Supporting Cast

Jongmin Park did double duty as the Monk and the Grand Inquisitor. The Korean has a rich bass sound that resonates in the Milan theater. His opening aria as the Monk, “Carlo il sommo imperatore,” showcased the bass’ rich middle sound and a powerful forte, especially in the lines “Grande Dio sol es s’Ei lo vuole.”

Then as the Grand Inquisitor, he first appeared in the “Auto-da-fé” scene, looking down on everyone as the deity that rules over the Spanish throne. His imposing character was fortified in the famed duet with Fillipo in Act three. Here Park sang with a rigid yet striking tone that was very different from the more impassioned tone of Pertusi. His solo passage “Allora, son io ch’a voi parlero, sire” displayed an imposing inquisitor who was in control of the scene, his voice building to fortissimo in the lines “Ed io, L’inquisitor, io che levai sovente.”

In the final scene of Act three, Park’s voice was also impressive as both Pertusi and he towered over the choral writing with booming sound. A lot of basses are often washed away by the chorus, but here Pertusi and Park soared, a perfect realization of Verdi’s musico-dramatic intention of the church and crown overpowered the people.

In Act four, Huanhong Li took over the role of the Monk and sang the final haunting lines “Il duolo della terra” with command, bringing all the attention to center stage. As Una voce dal cielo, Rosalia Cid showcased a gorgeous, lyric soprano with immaculate phrasing. Elisa Verzier was also impressive in the role of Tebaldo as she accompanied Garanča in her first aria, adding joviality to the scene.

In the pit Maestro Riccardo Chailly led a musically incisive performance that supported his singers well. Even when he used the full force of the Verdi orchestra (and thankfully, he did that a lot), the singers still came through crystal clear. In fact, they often seemed to ride that wave to greater heights. The success of Pertusi’s final “Ella giammai m’amo” was as much his success as it was Chailly’s ability to let the orchestra explode around him, the singer and the orchestra expressing the emotional floodgates of the king opening up. The same could be said of so many other major moments for the soloists.

Chailly’s opening prelude to Act two was particularly nuanced as the orchestra built toward Carlo’s entrance and the opening of “Tu che le vanità” started with a nostalgic brass fanfare that slowly built to the strings playing with such devastating force (there were some brass mistakes at the start of the opera and throughout the first intermission, you could hear the brass section rehearsing the final scene’s opening, which resulted in an extraordinary rendition). His drumroll finales were also quite astonishing as they emphasized the dramatic conclusions with great power. And when his singers attempted to pull back the tempo like in “non pianger, mia compagna,” Chailly responded immediately following his singer and adapting to her tempo.

One final word on color and texture, a great challenge in Verdi. A lot of conductors go overboard with the brass, often to the detriment of other textures and orchestral colors, resulting in a banda sound that cheapens the drama. Chailly knows how to let the brass loose during the forte sections but without ever ruining the overall balance. The result is impossibly rich in its impact and force. I don’t think I have heard orchestral playing of Verdi this good in a long time.