Staatsoper Berlin 2019-20 Review: Il Primo Omicidio

Romeo Castellucci’s Vision Goes From Dull To Relevatory

By Elyse Lyon(Credit: Monika Ritterhaus)

In its second annual Baroque festival, the Staatsoper Berlin spotlighted the work of two contemporaries, Alessandro Scarlatti and Henry Purcell, and the musical cultures of the Italian and English Baroque. Over 10 days and 25 musical performances, the program covered not only opera but a wide array of other material, from a Baroque harp recital to Jacobean masques, sacred motets to multimedia music theater.

Just like last season’s festival, it was a dizzyingly jam-packed event, rife with all kinds of excitement. One might dash straight from a Purcell semi-opera to a small-scale production by young artists; one might see a lighthearted Robin Hollingworth program one evening, and an ethereal Tallis Scholars performance a few days later. One production featured Instagram Stories and blacklights; another performance consisted of jazz improvisations. There were toccatas, fantasias, sonatas, trios, quartets, sextets.

The first full-scale work on the program, and the most anticipated event of the festival, was the premiere of Scarlatti’s “Il Primo Omicidio,” directed (in his Berlin operatic premiere) by Romeo Castellucci. A co-production with the Opéra national de Paris and the Teatro Massimo of Palermo, Scarlatti’s oratorio was conducted by René Jacobs leading the B’Rock Orchestra.

Rumor had it that some insiders expected poor reviews of the production. Such an expectation is not surprising: while many audience members flock to Berlin precisely for its most polarizing productions, flying in from cities all over Europe to enjoy unusual repertoire and avant-garde productions, it’s common for a premiere to be greeted by raucous booing of its director. Productions that enthuse one sector of the audience are likely to be received quite poorly by another. If local audiences and critics take a dislike to a production, even the best singers can fail to move tickets.

A recent run of Andrea Breth’s “Káťa Kabanová,” often denigrated as unduly bleak (though the opera itself is a bleak one), displayed the risks of artistic experimentation: despite memorable performances from a star-studded cast including Karita Mattila and Eva-Maria Westbroek, ticket sales were small enough that ushers invited audience members with low-priced tickets to sit in empty, higher-priced seats.

The stakes, therefore, were not small. The premiere of “Il Primo Omicidio” was sold out and crowded with press. Pens scratched on notepads; opera glasses winked from the balconies; Castellucci fans buzzed with excitement, and skeptics furrowed their eyebrows.

An Antiquated Worldview

The curtain rose on a semitransparent screen dividing the apron of the stage from the barely visible realms behind it. This scrim was fog-colored, smoke-colored, a glow of light building as milky shapes moved behind it.

Then came a rumble of drums. Now an apocalyptic chord from the orchestra, revelatory and forceful as the opening notes of “Don Giovanni.”

René Jacobs has recorded an excellent “Il Primo Omicidio” for CD. The sound that emerged from the orchestra pit was unlike that of his decades-old recording. Catastrophic, urgent, propulsive, it thundered through the house with devastating power: now a violin solo, and a racing pulse as the orchestra joined. The music surged forward, flaming with indescribable energy. It spoke of melancholy, of yearning, of joy. Each note simmered with individual meaning; each phrase was imbued with an ever-shifting array of moods and emotions. Under Jacobs’ baton, the music was as fresh and poignant as work composed centuries later.

At first, the narrative onstage seemed not to match the emotional poignancy of the music. Sacred oratorios, to modern mentalities, can seem dull, moralistic, and stiff, regardless of one’s attitude toward religion.

Thomas Walker, in “Mi balena ancor sul ciglio,” portrayed an intriguingly haunted Adamo, the liquid sweetness of his voice compellingly coarsened to depict a man terrified of God and still traumatized by his expulsion from Eden.

Birgitte Christensen’s Eva was particularly impressive, not only for the beauty of her voice—her low notes were rich and elegantly creamy, her high ones pure and soaring—but for her interpretation of the text, in which the Baroque-style repetitions of words and lines ceased to feel repetitive at all. Each line she sang added new and often surprising layers of meaning.

Nevertheless, the oratorio itself initially seemed less than electrifying, despite the riveting music. Though the singers’ interpretations highlighted the human side of the characters—Adamo’s traumatized mind, Eva’s grief and horror)—it was all too evident that the early 18th-century audiences for which “Il Primo Omicidio” was intended had a different understanding of humanity than today’s audiences do. For many in the audience, it may have been especially difficult to relate to the character of Eva, whom Scarlatti’s music and Antonio Ottoboni’s text portray as a decidedly submissive character. As for Dio, he was more threatening and authoritarian than loving and gentle, a characterization of God less acceptable to modern minds than Baroque ones.

This disconnect between Baroque worldview and modern audience was not aided by the sheer purity and goodness of Olivia Vermeulen’s Abele. Modern audiences attend the opera not to be presented with a moral lesson, but to enjoy an evening of engaging music and drama. Though Vermeulen’s Abele was a pleasure to the ears, her voice sweet, clear, and powerful throughout, there’s something decidedly boring about such a character’s unmitigated virtue.

Kristina Hammarström’s Caino, by contrast, was perhaps not dissimilar enough. One longed for a villain to provide dramatic excitement: a Scarpia, a Don Pizarro, somebody deliciously and thunderously malevolent. Hammarström’s Caino was scornfully rebellious but failed to communicate a sense of evil, or even of overwhelming anger.

Castellucci’s staging, in the first half of the work, offered few signs that it intended to alleviate such issues. Though the production was visually beautiful, it was also relatively traditional in its presentation of the work. Its minimalist staging provided no great departure from the conventional presentation of an oratorio. The grey scrim behind the singers never rose, and thus what action existed was confined to the apron of the stage.

The visuals consisted primarily of the play of light and color behind the scrim. For the most part, the shapes were abstract, reminiscent of classic works of color field painting. Some of the production’s touches were pointedly avant-garde—the smoke of Caino and Abele’s sacrifices, for instance, was represented by fog machines carried onstage—but such elements were sparingly used. The blocking was limited mainly to stylized poses and movements.

One arrived at intermission wondering whether this would be all: a beautiful rendering of a Baroque oratorio, its music played with electrical brilliance but its narrative somewhat tedious.

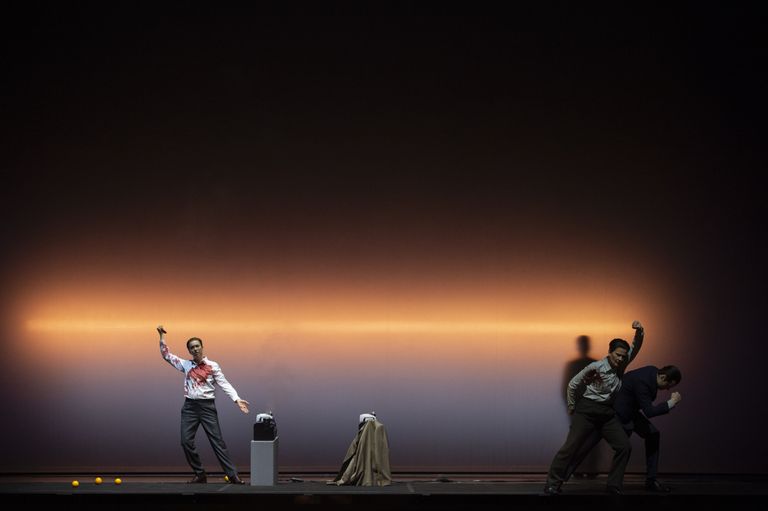

(Credit: Monika Ritterhaus)

A Revelatory Second Half

The curtain opened, for the second half, on a stage that had been transformed. One saw not a scrim, but a sort of diorama. The stage had become a stone-littered field, overgrown with unkempt grasses and placed against a nighttime backdrop of glittering stars. Caino tilled the soil alone, his gestures depicted in slow motion.

As before, the orchestra played with phenomenal energy, the music ominous, propulsive, dramatically persuasive and strikingly contemporary in its direct emotional appeal. Again, however, something seemed lacking in terms of the appeal of the work as a whole. As in the first part, the staging initially appeared traditional at heart.

Though the singers wore modern dress, the story was presented in a manner that was strikingly loyal to the Biblical narrative, from Caino portrayed as a tiller and Abele as a shepherd, to the sparse, rocky field that one could easily envision as part of Adamo and Eva’s post-Paradisiacal homestead.

Arttu Kataja’s Lucifero was not thrillingly vengeful or terrifying, but simply sinister. Hammarström sang competently, but her Caino lacked a certain emotional urgency: once again, her portrayal communicated primarily scorn and frustration, and “Perché mormora il ruscello” seemed little more than a nice bit of music, without clear significance or purpose. Vermuelen’s Abele continued to impress with the luxurious purity of her tone, but Ottoboni’s text is exasperatingly unsubtle for audiences accustomed to more literary nuance.

But Castellucci, as it suddenly became clear, had not yet demonstrated the fullness of his vision. Only as Caino raised his hand to kill his brother did the entire production click into place. All at once, the apparent traditionalism and seeming tediousness of some aspects of the production proved to have been building up a store of latent energy ready to be unleashed in the second half.

Castellucci’s method, here, sounds almost silly. As Caino raises the stone with which he plans to murder Abele, a child actor appears behind him, dressed and posed in an identical manner. Instead of Hammarström’s Caino, it’s this child double who beats Abele to death with a rock. Over the next several minutes, each character is replaced in this manner. From that point on, it’s the child doubles who portray the action. The adults sing from the orchestra pit or else from a niche above it. Meanwhile, the children move their mouths in a mimed “singing” so well-rehearsed that one is almost tricked into thinking the adult voices come from the children’s mouths.

The effect was profound. For a few heartbeats, one smiled at the children pretending to sing; then, an instant later, the extraordinary effect of the staging hit. All at once, Caino was a figure with whom one sympathized and whom one understood. His jealousy of his brother was not an expression of pure evil, but the frustration any child with siblings feels at one point or another. It became disturbingly easy to see the appeal of Lucifero’s temptations: “Become as powerful as God! Fight hard against Heaven,” Lucifero inveigled Caino. One thought, then, of the whole mass of popular children’s literature, so much of which revolves around children’s fantasies of unlimited power and valor and fame. One felt the heady intoxication of Lucifero’s words for oneself, and one felt empathy with the child led astray by them.

There are times when a production communicates concepts and driving ideas that, no matter how interesting, lie far from the director’s stated intentions. “Il Primo Omicidio” was not one of them.

Castellucci, in the interview included in the program book, says that his aim in using the child actors was to overturn our automatic identification, as audience members, with the forces of good rather than those of evil. This is wrong, he says: “We are Cain. I am Cain. The bad guy is me, Romeo Castellucci.” This idea came through clearly, with breathtaking power and impact. Not only did it retain its effect through the entirety of a second viewing of the same production, but this effect actually increased: one heard the first half of the work with new understanding, not as a creaky 300-year-old contraption but as a piece in which the story is—or can be—just as vital to the present moment as the music became, in Jacobs’ revelatory interpretation.

Not every critic or audience member can have been fully pleased—although, unusually enough for a Staatsoper premiere, Castellucci’s curtain call occurred without audible boos. Inevitably, some among the audience may have been displeased by Castellucci’s vision, or unsatisfied by a cast that, while frequently impressive, did not (particularly on the first night) entirely rise to the high standard set by the phenomenal work of Jacobs and the B’Rock Orchestra.

To those receptive to Castellucci’s style and the power of Scarlatti’s music, however, the evening was awe-inspiring, transformative, and both musically and dramatically unforgettable. It made for a remarkable start to the Staatsoper’s second Baroque festival.