Seattle Symphony 2022 Review: Verdi’s Requiem

A Last-Minute Replacement Throws Things Off A Bit

By John CarrollDuring my 40 years of being obsessed with opera, and five years singing in major choral works, I realize it’s a bit odd that Verdi’s Requiem never entered my sphere. I have never experienced it live, nor even owned a recording. Please do not shame me. I am somewhat familiar with a couple of the most famous sections: the driving drama of the “Dies irae” opening allegro agitato has been used in film soundtracks, and the “Libera me” movement is famous for being a monumental soprano challenge.

All this is to say, the Seattle Symphony’s performance on June 17 was my first full exposure to the work.

It’s been jokingly referred to as “”Aida” without the sets and costumes,” which is a short cut way to convey Verdi’s stylistic mix of sacred mass and Italian opera. I certainly sensed that in Seattle Symphony’s interpretation, but the mash-up of styles felt disjointed and kept me at a distance. I was impressed by the scale and effort of the endeavor, but rarely dazzled and never moved spiritually. Since this was my first Verdi Requiem, I cannot say how much of this reaction was due to the piece itself, or how much was due to this specific performance – probably a bit of both.

Even not knowing the work, I sensed from the get-go that conductor Giacomo Sagripanti found it challenging to make plausible the transitions within and between movements. His tempo changes seemed to take a moment to click in. Like a commander steering a large ship, there was a delay in the responsiveness of his vast musical forces—a huge choir, a mammoth orchestra, and four operatic soloists.

Verdi’s score has many sudden switches, from fortissimo to pianissimo and then back to fortissimo again, presumably reflecting his point of view on the far extremes of religious anguish and redemption. Sagripanti fully pushed those extremes—the opening bars, featuring cello, were so hushed that I could hear the rustling of program pages in the top balcony better. And at the other end of the sonic spectrum, I do not know if I have ever heard a fortissimo that matched the volume of sound Sagripanti was able to conjure for the “Dies irae.” The choir and orchestra were beyond robust and the timpani drums shook me to my core. The distant trumpets in the “Dies irae” were played from high positions in the two top balconies, creating an engaging, three-dimensional aural effect.

The Seattle Symphony Chorale lacked warmth of tone and focus in the opening movement. Perhaps the COVID-19-preventative facemasks they were wearing cut down some vocal overtones. The most impactful moment for the group was the jubilant “Sanctus” movement, an elaborate fugue for double choir. Their articulation of the eight different parts was so crisp, even through masks, that it was possible to follow the intricate melodic path of the piece. The choir provided beautiful tone in the soft sections and vibrancy throughout. The “Hosanna” section, when all the moving vocal lines joined together, was especially radiant.

The first entrance of the four soloists on “Kyrie eleison” was a bit messy, as the singers failed to pass the short rising and falling phrases to each other with any sense of a consistent line or blend. They had each such different styles and approaches that it was as if they had wandered onstage from different operas and just started singing ad hoc. This lack of cohesion may be attributed to the fact that soprano Katie Van Kooten was a last-minute replacement for Latonia Moore, who withdrew at very short notice due to illness. Van Kooten was very good–more on her later–and I do not want to suggest at all that the disjointed feeling was her fault; I just point this out as it is not hard to imagine that such a significant switch after rehearsals had already begun would throw things off on opening night.

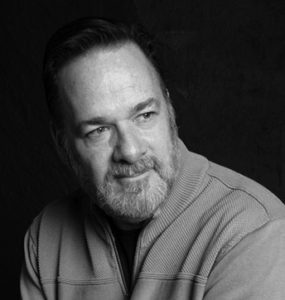

Giacomo Sagripanti, conductor, and Dashon Burton, bass-baritone (Photo credit: Brandon Patoc)

I’ll cover the soloists from the low voices up, because I want to begin with bass-baritone Dashon Burton, who made the strongest impression—and this despite not having as many featured moments as the others. Burton was absolutely mesmerizing. We think of bass singers in a vocal quartet as being there to provide a solid foundation of tone upon which the tenor, mezzo, and soprano can build—and Burton certainly did that, firmly grounded in pitch, tone, blend, and volume.

But he was so much more! In his solos he grabbed and held focus, leading us on a rich, multilayered existential journey. There was a commanding sense of alarm in the first real solo moment of the work, his “Mors stupedit et natura.” His repeated utterances of “mors”–death–were unnerving. His spotlight moment in the “Confutatis” section was gripping due to his immaculate phrasing, nuanced use of dynamics, and powerful high Es. Burton had a music stand, as did the others, but rarely relied on the score; he instead peered directly into the audience, forming an intense connection. His stage presence was galvanizing.

Despite Van Kooten being the last-minute replacement, it was tenor Bruce Sledge who gave the impression of being out of sync. His energy was disheveled and he projected an uncomfortable feeling that at any moment he might lose his place. His face was buried in the score, which was held in his hands instead of resting on the music stand like the other soloists. His tenor was reedy in quality and did not fill the space, and his phrasing was choppy.

The mezzo-soprano soloist has several prominent solos and duets in Verdi’s Requiem. Silvia Beltrami rose to the task, bringing an authentic Italian operatic flair to the piece with her plummy voice and grand stage presence. She was connected to the drama of the work, as seen in her facial expressions, hand gestures, and bearing. “Lux aeterna” was her highlight, sung with a lovely luminescence of tone that rang out into the venue as if her voice had become the eternal light she was singing about. There were many other moments where I appreciated Beltrami’s refined artistry, especially when she pulled way back on her operatic vocal posture to eerily match the soprano’s chant-like tone in the unison acapella measures of “Agnus Dei.”

Soprano Katie Van Kooten has sung Verdi’s Requiem several times before, no doubt a key factor in her ability to step in at such short notice and deliver a superb performance. So much heavy lifting falls to the soprano in this work, much of it in quite a high tessitura. Van Kooten has a vibrant voice with a shimmering, ethereal gleam. Her control of dynamics was impressive—I lost count of how many times she expertly deployed a diminuendo, and Verdi’s score is liberally festooned with them—and her attention to detail was superb, such as the well-articulated trill on the phrase “Transire ad vitam” in the Offertorio section.

Though her voice had volume and presence, I found her more effective in the softer moments than the dramatic ones. Verdi’s soprano line has many quiet suspensions, which Van Kooten assailed confidently, except for one very exposed high B-flat that was a little wobbly. Everything marked “dolce” or “dolcissime” was delicately sung, but big bursts of passion, like her climb to a held high C at the end of “Libera me,” lacked climactic power. That she stepped into the performance on a moment’s notice makes Van Kooten’s singing that much more of an impressive accomplishment.

Categories

Stage Reviews