Reviving Saint-Saëns’ Lost Masterpiece – Dr. Hugh MacDonald on Collaborating with Odyssey Opera on ‘Henry VIII’

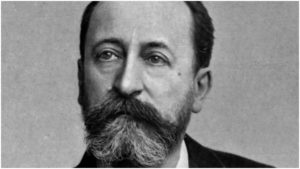

By John VandevertDespite his relatively subdued presence in contemporary performance repertoire, during his time Camille Saint-Saëns was known across the world for his exceptional aptitude and fiercely developed intellect.

Having begun life as a piano prodigy and gaining compositional mastery shortly after with his “First Symphony” at the age of only 17, Saint-Saëns is possibly one of France’s most transformative, yet erroneously overlooked, composers ever. The announcement that the Boston-based company Odyssey Opera—who specialize in “offbeat, neglected repertoire,” as journalist David Weininger puts it—would be releasing their 2019 recording of the fully reconstructed version of Saint-Saëns’ unjustly overlooked grand opera “Henry VIII,” was consequently almost too good to be true. Written in the early 1880s, after a fortuitous meeting with librettist Leonce Detroyat during a trip to Spain, and the product of a five-man team, the nettlesome work that followed, riveting musical research at the Royal Library, and many rounds of edits on the part of Saint-Saëns, “Henry VIII” came to be one of late-19th century France’s most beloved operas. An operatic marvel with bold costumes, heavily detailed sets, and luxuriously dramatic music suiting the liberally conservative tastes of its composer, this opera came to be one of the most performed French operas. In 1889 it premiered at the Royal Opera House and in 1895—12 years after its first performance—it premiered at La Scala in Milan, received with much fanfare across the European world.

What has happened since then? Once the Fin-de-Siecle—and it’s optimistic partner, the Belle-Epoque—came to an end, the tides of modernism, impressionism, and neoclassicism were in vogue. Because of Saint-Saëns’ obstinacy towards such aesthetics, his music rapidly fell out of favor among audiences now captivated by the watercolor rise of Debussy and Ravel in the West, along with Scriabin and Stravinsky in the East. It therefore took time for this opera to reemerge: specifically 72 years.

In 1991 “Henry VIII” received its first second-wave premiere at the Théâtre Impérial de Compiègne, under the guiding hand of Pierre Jourdan, while its American premiere was in 1974 by Bel Canto Opera. Something was missing from nearly every one of these performances, however, and that was Saint-Saëns’ complete musical picture of “Henry VIII.” The operas had undergone extensive cuts due to the sheer length of the original work.

But in 2019, with the help of leading Saint-Saëns scholar Dr. Hugh MacDonald, Odyssey Opera set about the ambitious project of reconstructing “Henry VIII.” For the first-time since 1883 the opera was performed in its entirety. With a huge orchestral body and choir, with top singers as soloists, Odyssey Opera’s reconstruction of “Henry VIII” has not only restored history but has also made history as well. Now audiences are able to come up close and personal with this seminal piece of literature.

To help contextualize “Henry VIII”‘s importance and delve deeper into it, OperaWire interviewed Dr. MacDonald. In the interview, he revealed many fascinating pieces of information regarding Saint-Saëns and his once-popular operatic work.

As a Saint-Saëns Scholar

Dr. MacDonald’s work as a Saint-Saëns scholar emerged out of his love of 19th century French opera, having done his Ph.D. on “Les Troyens,” and the operas of composers like Saint-Saëns, Berlioz and Bizet. In 2019, he published the book, “Saint-Saëns and the Stage” which took an investigative look at the composer’s many unexplored operatic works from a deeply passionate perspective, attempting to understand how these operas came to be and why they were so important in the development of Saint-Saëns’ musical legacy. Dr. MacDonald explains that his interest in Saint-Saëns was the result of the realization that a significant portion of the composer’s operatic works were hardly known by the public, with scholarship on them all but missing.

As he shared, “I knew ‘Samson et Delilah,’ and I realized he wrote a great amount of operas and yet there was no sign of these operas in recording lists or opera house programs. So it seemed to me there was room for serious study, and I never really thought I’d do it myself.”

He revealed that his book project was pitched to many and often passed over. It was thus, after his retirement from teaching, that he decided to do it himself. The book, as Dr. MacDonald puts it, “places those works in the public eye if anybody wants to pursue them, and I’m thinking principally of opera houses and recording companies who really should be looking at these things and finding an audience.”

This is a point he would later bring up in reference to the legacy of lesser-known operas like “Henry VIII” being in the recording studio rather than the stage, revealing just how poignant the work of Odyssey Opera really is. After sharing concerns over the lack of Saint-Saëns’ presence in the repertoire of classical singers today, Dr. MacDonald brought attention to the ubiquitous problem that, “there is too much music everywhere. In Saint-Saëns case, he wrote such a vast body of music that it’ll never be well known, even if you specialize in him.”

When probed about the legacy of Saint-Saëns and where the composer fits into the larger framework of music history, Dr. MacDonald noted the trickiness of this question. During his lifetime, Saint-Saëns was one of the most influential composers in the world. With the dawn of modernism, however, his name became a symbol of antiquarian tastes and quickly fell from fashion. Although his name is known today by the works “Danse Macabre,” “Le Carnaval des animaux,” (“The Carnival of Animals”) and “Samson et Delila,” along with his “Symphony No. 3,” and his second and fifth piano concerti, hardly anyone in the 21st century is aware of his phenomenal body of sacred music, chanson, instrumental works, and operas. This disparity between what Saint-Saëns created and what we know of him seems enormous.

Dr. MacDonald revealed the reason for this being his conservative yet richly developed musical style, comparable to the likes of Tchaikovsky and Dvorak. Yet, as MacDonald said, “He doesn’t have Tchaikovsky’s emotional intensity, and he doesn’t have Dvorak’s local color.”

There is another reason, also: “He lived too long. He lived into the 1920s, when his kind of music was being radically rejected by the mainstream. It wasn’t jazzy, and he was quite a reactionary. He didn’t like Debussy. He put himself outside the stream of modern music, and in the 1920s it was really impossible to treat him seriously.” And yet, “Saint-Saëns was absolutely mainstream in his lifetime, and enough of his music was fully accepted after his lifetime. But of course he was out of tune with modern trends, as many old composers will tend to be.” Thus, the break in the legacy of Saint-Saëns was inevitable. Although he is widely known, his music remains absent from programs.

“Henry VIII”

Considered the “French Beethoven” by scholars with a love of intellectual and scientific pursuits, Saint-Saëns was fully committed to bolstering and obeying the rules of the French style with a large respect for German classicism, yet all the while retaining a sense of levity in his language. Attracted to the Germanic greats like Mozart, Mendelssohn, and Beethoven, along with a passionate love of the French baroque through Rameau and the Oriental allure of the Middle East, Saint-Saëns was the epitome of a truly cosmopolitan individual. And like all intellectuals, he was aware of the political climate around him, being Republican in leaning and a strong advocate of public music education.

Thus, in the late 19th century, following the end of the Franco-Prussian war, the disaster of the Paris Commune, and the establishment of the Third Republic in the 1870s, Saint-Saëns was aware of the conflicting worlds of modernism and traditionalism. From this nexus of national development, his opera “Henry VIII” emerged. Both loving and reviling Wagner, Saint-Saëns’ opera was a way to negotiate the rise of populism and musical modernism, showcasing the fragility of power through the guise of a well-known historical period.

This was a technique the composer was very fond of using throughout his career. When asked why this opera had been so joyously accepted by French audiences in 1883 when it first premiered at Paris Opera, going on to have another successful premiere at La Scala in 1895 before disappearing in the early 20th century, Dr. MacDonald replied, “The music is superb and it has a great dramatic issue at the beginning and throughout; it was a well-known historical episode; and, of course, divorce and the Catholic Church come into play… it gives it a very strong dramatic core.”

He continued, “It also requires splendid settings: Tudor background is very popular. In those days companies… made every effort to produce splendid decor, sets, and costumes. These all made a very spectacular and colorful event, plus the power of the music.”

This opera would have been a marvel to see: a truly incredible evening for 19th century audiences. As Dr. MacDonald emphatically stated, “It’s up there with the great operas of the period… The singers of the period wanted to sing it, and the stage directors wanted to stage it.”

Dr. MacDonald stressed, however, that “Henry VIII” was much more an exemplification of what Saint-Saëns thought well-executed and truly beautiful opera was, rather than a sociopolitical allusion to his Republican leanings.

“Saint-Saëns was a Republican by instinct, supporting the Third Republic. He was a conservative in his tastes, but I don’t believe the story was based on anything of that kind [politically motivated]… It wasn’t his choice, it was put to him by somebody else [director of Paris Opera Auguste Vaucorbeil].” Modern audiences can therefore understand “Henry VIII” as Saint-Saëns’ ideal grand opera, the pinnacle of what good opera should be in his mind when faced with the specter of Wagner. “Saint-Saëns was much more focused on constructing a good opera than making any kind of statement… He was making a point of what music should be, how to make it beautiful, and perfect within classical guidelines,” Dr. MacDonald added.

Another peculiar part of the opera are the references to English, Scottish, and Irish folk-music, the music of which was sourced from the pages of 16th-century manuscripts collected on a trip to the Royal Library in London. When asked about this seminal element, MacDonald noted, “The effect was to give a sense of period drama more than anything…The Irish and Scottish were elements all composers included in their ballets because they are colorful and danceable. Again, he was not making a point, he was interested in local color. Especially for ballet. And in later life he got interested in Egyptian, Persian, and Greek music.” Yet, innocuous as it may be, he notes that, “He was a real pioneer in this field.”

Opera and Editing

As Dr. MacDonald mentions in his book, “Henry VIII” underwent quite a furious few years of editing following its first draft in 1882. It was orchestrated and revised significantly before its first performance in 1883. Due to the appreciable length of the work—nearly four hours in length—multiple parts over the years were cut from it, however. This led to the original version being, in effect, “lost.” Though the parts were available to be performed they were never—or rarely—accessed by companies.

What did this mean for “Henry VIII?”

Dr. MacDonald revealed that, “The control of the opera was not always in the composer’s hands. You don’t tamper with a Wagner opera, [yet] people made cuts with almost everything else. It was standard at the time.”

It was not out of the ordinary for scenes to be cut, rearranged, arias to be squeezed into spaces not originally there, and musical moments to be shortened per the needs of the staging. In most cases directors and composers would find out once the opera had its first premiere that certain scenes, orchestrations, choreographic movements, and arias simply were not working or harmoniously flowing within the work as needed.

“Management had control due to copyright rules. So composers themselves would often find out some things worked and other things didn’t. Saint-Saëns revised many of his operas, in some cases many times.”

“Henry VIII” was no exception. Being the general editor of the Barenreiter “Hector Berlioz: New Edition of the Complete Works,” Dr. MacDonald noted that it is nearly impossible to figure out the reason behind the Saint-Saëns’ editorial decisions.

“He composed a considerable amount of music, and some of it was staged at the first performances, and later in different versions. Decisions were made for all sorts of reasons. As an editor, it’s almost impossible to know why. All you can do is establish what was played and when. To establish ‘why’ is much harder,” he added.

When dealing with operas and contemporary printing, Dr. MacDonald revealed that one of the most important aspects is to supply every version you can and allow the directors to make their choices and further requests, as shown in his collaboration with Odyssey Opera.

“[When] printing operas in modern traditions, it’s very important to put out all the music you can find and place it within the context of the opera itself and allow modern conductors and directors to choose which version they need,” Dr. MacDonald noted. “I’m the first to recognize that when you’re working in the theater, authenticity is the first thing to go out the window and you really have to adjust to your current needs.”

When it comes to opera, because there are multiple factors that must be adjusted for every performance regarding audience, venue, and other constituent parameters, adjustments are always made. Odyssey Opera and Dr. MacDonald’s collaboration is the epitome of the performance-musicological coalition, and one of his favorite parts of his work.

“As an editor, I’m very pleased when a conductor comes to me and tells me ‘We’d like to do this scene and that scene.’ This is exactly what happened with Odyssey Opera. The conductor decided to restore some of the music that went missing from many of the scores.”

While many scores were available, none had the complete orchestral score to the original opera.

Saint-Saëns’ legacy is not in dispute but the quality of his legacy is in need of redemption. The impact of Odyssey Opera’s recording project cannot be understated. The company’s 2019 recording is the first reconstructed production—recording or otherwise—of Saint-Saëns’ “Henry VIII” since its premiere nearly 140 years ago. It was sung by sensational singers, given life by highly adept musicians, and led by an exceptional conductor. The importance of what Odyssey Opera has achieved for not only this opera but the legacy of Saint-Saëns is groundbreaking. It sets a new precedent for the merger of music historiography and the performing arts, bringing together two sides of music which rarely combine. One would be right in expecting this opera to grace the stages of England and Italy as a result of Odyssey’s successful reconstruction.

Dr. MacDonald shared similar sentiments: “The biggest opera houses around the world ought to be doing these operas. In particular, Covent Garden.”

He was hesitant, however, to state that Saint-Saëns’ operas—other than “Samson”—would ever get as much coverage as they did in the 19th century. Dr. MacDonald does know where they would and could flourish, however.

“Saint-Saëns’ operas are never going to become more widespread in the opera house, but there is a future for them in the recording studio, which is where unknown operas need to thrive. Record it once, and people can hear it. If they aren’t recorded people don’t listen to them, they don’t know what they sound like,” he noted.

It is clear how vital the work of Odyssey Opera, and the work yet to be done in the preservation of lesser-known operatic literature for audiences and researchers alike, is. Without proper recordings, operas like “Henry VIII” will never get their revival, and instead be relegated to the halls of music history without so much as a chance to contemporaneously flourish. In 1917, Saint-Saëns stated that he wished for “Henry VIII” to get a revival.

Now his wish has been fulfilled, thanks to Odyssey Opera and Dr. MacDonald. Who will be next?