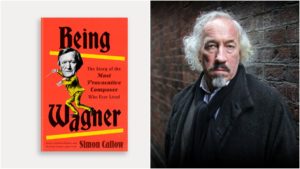

Q & A: ‘Being Wagner’ Author Simon Callow On Discovering the German Master Anew

By David SalazarNext to William Shakespeare, Richard Wagner is one of the most written about figures in human history. His enigmatic qualities coupled with his unquestionable genius make him someone who fascinates as much as he bewilders and antagonizes. Volumes have been written about the composer from virtually every conceivable angle, whether it be his family, his adventures, his psychology, his philosophy, his art, etc.

And yet in recent months, yet another work was added to the massive and growing oeuvre surrounding the German master. But Simon Callow’s “Being Wagner” is no superficial look at the titan. It narrates his story from an amusing perspective, keeping the reader engaged through entertaining and ironic tone that never wavers. Those who have never read about Wagner will find this a perfect introduction while those who have Wagner books lining every one of their bookstands will still find the flavor of Callow’s writing to be incisive and ever-exploratory.

OperaWire recently spoke to Callow about his interest in writing the biography and the unique insights he acquired from the gargantuan task.

OperaWire: Where did the inspiration to write a biography on Wagner come from?

Simon Callow: I did a show about Wagner for the Royal Opera House in London in 2013, to commemorate his bicentenary. I discarded a great deal of the research I did for the show, which was a theatrical evocation of the man; the book used that discarded material to give a more detailed, rounded picture of the man and his mind.

OW: There are a ton of biographies on Wagner as it stands. What went into your deciding how yours would be different from the others?

SC: I had formed a very strong impression of Wagner as a man of the theatre. His books of theory, though enormously long and somewhat dense, are radical, but he was no mere theorist: his ideas had very practical implications, which he put into effect with great skill. He was himself a formidable actor, and could have made a very successful living at it had he chosen not to be the greatest composer of the 19th century.

OW: What was the most fascinating thing you learned about Wagner that you didn’t previously know?

SC: That he hated militarism and political nationalism. He believed in the German soul, which was a very different thing from the German nation.

OW: You have a humorous style throughout, keeping a relaxed reading experience on one of the world’s most controversial (and in some places, most hated) figures. What were the challenges of achieving that?

SC: When writing about monsters – I’ve covered a few – it’s probably best to maintain a certain ironic perspective.

OW: What is your favorite Wagner opera? And why? Least favorite?

SC: I’m torn between “Rheingold,” for its astonishing compression and originality, and “Meistersinger” for its amplitude and indulgence in everything Wagner said opera should have: arias, ensembles, choruses, and its essential charitableness to towards human weakness.

The one I struggle with is “Siegfried,” possibly because I’ve never seen a satisfactory production of it.

OW: Everyone that knows about Wagner has a perception of him. How did yours change from the start of this journey through the end of it?

SC: I ended up agog at his titanic productivity, and his tremendous loyalty to his talent (if to no one else).

OW: For you, what do you believe makes Wagner such an important figure?

SC: By sheer will power he imposed himself on music, bending it into unprecedented shapes, pushing its boundaries to the limit and beyond. He opened up the path of revolt against form along which everyone else followed, free to innovate as they thought fit.

OW: You know Wagner rather intimately at this point. If you could ask him one question, what would it be and why?

SC: I’d have to challenge him about his insane and wildly inconsistent anti-Semitism. I’d like to put him on the psychiatrist’s couch about that.

OW: Wagner left behind a lot of unfinished works. If you had to choose one, which would you wish he had gone back and completed?

SC: The Jesus play from 1849, for which he wrote an outline at exactly the same time as he was beginning to imagine the Ring. His Jesus was a revolutionary. Tantalizing.