Page to Opera Stage: Massenet & Puccini Create Plot Holes and Dramatic Tension in Adaptations of ‘Manon Lescaut’

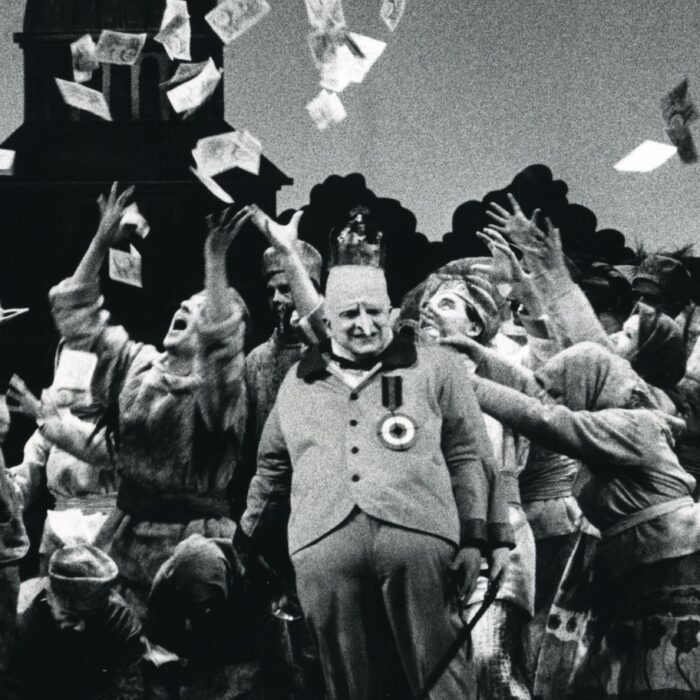

By Carmen Paddock(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

“Page to Opera Stage” looks at stories–real-life or fiction, old and new–that have inspired operas, and the ways these narratives have been edited and dramatized to fit a new medium. In this instalment, we look at one novel–Abbé Prevost’s ‘Manon Lescaut’–and the two (very different) audience favourite operas it inspired: Jules Massenet’s “Manon” and Giacomo Puccini’s “Manon Lescaut.”

When Antoine François Prévost d’Exiles–perhaps better-known today by his ecclesiastical title as the Abbé Prévost–began publication of his sprawling seven-part novel “Mémoires et aventures d’un homme de qualité qui s’est retiré du mond” (“Memoirs and adventures of a man of quality who has withdrawn himself from the world”), he was far from such retirement himself.

Born in 1697, Prévost had travelled the world in the army and in pursuit of ill-fated love affairs between interrupted novitiates and eventual vows with the Benedictines of Jumièges in 1721. His travels–and affairs with women disapproved of by his colleagues–did not end here. He fled his monastery in 1728 after an unplanned absence earned him royal censure, settling between England and the Netherlands and developing a love of English literature. The novels inspired by this love often made claims to truth through an active narrator character: a common characteristic of French literature of the day. They were, however, fabricated entirely from an active imagination. The seventh volume of “Mémoires’ includes ‘Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut,” a novel-within-a-novel that soon took on a scandalous life outside of the overarching narrative. ‘Manon Lescaut’ was initially published in Paris in 1731 but was soon banned in France, finding fame and readers instead through pirated printings.

‘Manon Lescaut‘ sprawls across times, places, and jealousies. The novel opens in a similar way to Dumas fils’ “La dame aux camelias” and Mérimée’s “Carmen“: an unnamed gentleman narrator meets a beautiful, soon-to-be-dead woman, and after her death her young, infatuated lover appears to recount his story. Prévost overcomplicates his romance, lacking Dumas fils’ tragic simplicity, and never reaches the darkest compulsions at the heart of Mérimée. The result is a narrative that moves from one trial to the next without reflection, missing themes of exploitation and inconstant moralities in a patriarchal society. Despite its romantic sentimentality and ever-changing milieu, the novel is a frustrating read in its myopicness.

Despite its weaknesses on the page, its young, impulsive lovers make “Manon Lescaut“ prime fodder for operatic adaptation. 153 years after Prévost’s publication, and within nine years of one another, Jules Massenet and Giacomo Puccini had both retold the story at the Paris Opéra-Comique (1884) and Turin’s Teatro Regio (1893) respectively. Indeed, Puccini argued his case for adaptation so soon after Massenet’s smash hit:

Manon is a heroine I believe in and therefore she cannot fail to win the hearts of the public. Why shouldn’t there be two operas about Manon? A woman like Manon can have more than one lover. […] Massenet feels it as a Frenchman, with powder and minuets. I shall feel it as an Italian, with a desperate passion.

With the showcase arias offered to sopranos and the timeless romantic tragedy–somewhat simplified from Prevost, yet in markedly different ways–both operas were hits upon their premieres and have remained repertoire staples to this day.

Plot Holes and Plot Devices

Both “Manon” and “Manon Lescaut” start and end at the same place: Des Grieux’s first meeting with Manon, and then Manon’s death (Prevost’s original framing story is gone). Both operas also remove a handful of the doomed lovers’ splits and reunifications, focusing instead on one key instance each. Lastly, both excise the most sensational drama: Manon’s brother is not suddenly murdered over a debt at cards, Des Grieux does not successfully break Manon out of an asylum before her eventual recapture and deportation, and the still-unwed couple do not win love and derision in New Orleans before Manon succumbs to her ill-treatment.

The resulting stories, with conventional yet satisfying ups and downs and easily comprehensible plot progressions, are far more suited for an evening at the opera. But the selections from the novel chosen for Massenet’s and Puccini’s visions best serve their unique musical and dramatic styles while highlighting themes lost–or perhaps never present–in Prevost’s overcrowded narrative. These operas become compelling love stories that lead to ruin, sympathetic without mawkishness, complemented by their composers’ respective musical languages.

Massenet, alongside librettists Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille, focuses intently on the novel’s first half. Starting with their meeting and wild plan to run away, the audience sees their precarious but happy life before Manon reluctantly betrays Des Grieux at his family’s request. She takes up a more secure, riches-filled existence as the rich Brétigny’s mistress while he becomes a priest; an Abbé, incidentally, similar to the original author. She later seduces him in his Saint-Sulpice parish. They reunite, and a botched evening at the gambling tables propels Manon to imprisonment and death, skipping hundreds of pages forward in the novel and keeping her demise in France rather than its North American colony. With audacious gambling their only sin, this incarceration and ill treatment feels slightly overblown in the Meilhac/Gille libretto; it falls to stage directors to create the necessary tragedy.

Puccini and librettist Luigi Illica, on the other hand, jump from Des Grieux and Manon’s elopement to Manon’s luxurious life as Geronte’s mistress; a brief conversation with her brother reveals that she left Des Grieux for a more secure situation, but we do not see them together until Des Grieux arrives to win Manon back later in the act; a crucial difference in pursuer vs. pursued, in comparison to Massenet’s reworking. When Geronte realizes he has been tricked, Manon cannot flee in time as she collects her treasures. She is arrested for theft and sentenced to deportation. As in Prevost’s novel, Des Grieux begs passage with her. Manon, however, dies of exhaustion soon after arrival in the “desert” outside New Orleans–American geography not being Puccini’s strongest suit–rather than see another chapter of jealousy unfold.

Massenet’s “Manon” brims with opéra comique trademarks: sparkling melodies, dialogue connecting distinct numbers, and generally lighthearted antics throughout the majority of the plot. While ultimately ending in tragedy and the death of the soprano, the genre title is earned through these French operatic stylings. By the time “Manon” reached the stage Massenet was well-known for both opéra comiques and grand operas, such as “Hérodiade” and “Le roi de Lahore.” “Manon” became the next–and biggest–in this string of successes, and perhaps the earliest of his works to enjoy a consistent place in the worldwide operatic repertoire.

While only writing nine years after Massenet, Puccini found his first commercial success in the verismo style. As a need for gritty realism gripped Italian opera, ballets and effervescent chorus numbers gave way to a desire to portray the everyday, the tragic, and the human. Unlike Massenet, Puccini had a reputation only for misfires when “Manon Lescaut” premiered: his previous attempt, “Edgar,” had been a grand medieval epic out of step with the current vogue. The success of “Manon Lescaut” catapulted Puccini to stardom and a firm place in the canon with his later output.

By selectively adapting Prevost’s novel into the operatic genres they perfected, Massenet and Puccini emphasize different themes in the erstwhile sensational morality tale. The earlier opera revels in Manon’s determination to have fun, glamour, and riches in her youth, placing the heroine as key driver of her social climb–the first four acts–and fall from grace–Act five alone. Massenet and his team fill the background with men orientated towards similar pleasures, all of whom get away with their lust and greed.

Puccini and Illica’s retelling, however, skips to Manon’s discontentment having given up love, emphasizing her victimization from the second act onwards and losing the growth of her romance with Des Grieux. She is similarly brought down by avarice, but she has been groomed and kept powerless. Acts three and four see nothing but her destitution and deportation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ruxBoYqWs8Q

L’histoire de Manon Lescaut

Prevost gives readers Manon’s entire story through the eyes and explanations of Des Grieux, recounting his lost love to the unnamed narrator. Manon is revealed overwhelmingly through her lovers’ recollections, herself speaking infrequently.

Massenet and Puccini both work in Manon’s introductory bashfulness, having her introduce herself as others call her: “On appelle Manon” and “Manon Lescaut mi chiamo,” respectively. The librettos, however, turn this narration around. Manon is the primary voice throughout Meilhac and Gille’s narration: in the opening scene she mourns her perceived loss of freedom on her way to the convent and first suggests to Des Grieux that the pair run away. This voice continues throughout Massenet’s opera, letting the audience in on Manon’s most private and trivial reflections.

Des Grieux takes a more equal role in Illica’s retelling, opening the first and third acts through his eyes. However, Manon holds focus in Acts two and four, giving her reasoning for leaving Des Grieux and voicing her own despair at her exile and fatal illness.

The result is a wholly different tale from Prévost’s novel, placing both operas closer thematically despite their different styles. Instead of seeing Manon’s quest for riches–and then survival–through the eyes of her naive lover, she gives full voice to her desires and doubts. These stories thus feel more modern, casting Manon not as temptress or victim but as agent in a society set against her.

Puccini proves himself correct in his assertion that a woman like Manon can have several lovers: both his and Massenet’s versions are unique, equal retellings that offer astute character studies alongside sumptuous melodies. Additionally, both retain their place in today’s operatic canon with their still-timely quasi feminist lens. Improving on Prevost’s text through plot simplification and a focus on the heroine’s journey, “Manon” and “Manon Lescaut” give audiences two sides of a woman whose quest for pleasure and security can only end in disaster.

Prevost’s “Manon Lescaut” can be found at Project Gutenberg in a translation by Jalmari Hahl. Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille’s libretto for Jules Massenet’s “Manon” and Luigi Illica’s libretto for Giacomo Puccini’s “Manon Lescaut” are also available online.

Categories

Special Features