Page to Opera Stage: The Inspiration and Adaptations of Carmen

By Carmen Paddock“Page to Opera Stage” looks at stories – real-life or fiction, old and new – that have inspired operas, and the ways these narratives have been edited and dramatized to fit a new medium. This week’s article looks at the stylings of Prosper Mérimée’s novella “Carmen” and Bizet’s streamlined operatic adaptation.

In terms of French literary history, Prosper Mérimée may not be the first name to come to mind. However, the historian, architect, and writer earned himself a special spot through his mastery of the mid-19th century novella and through his translations of foreign fiction for his contemporary French audiences.

Russian literature held a special place in his heart; he undertook Russian lessons with Madame de Langrené, a Russian émigré and former dame of honor of Tsar Nicholas I’s daughter, in order to read all of Pushkin in the poet’s original language. There is some debate as to the exact timeline of his studies and discoveries of these works, but his translations of Pushkin and Gogol in the 1840s and 1850s introduced these iconic writers to a wider French-speaking audience. Furthermore, this work may have inspired Mérimée’s most famous story.

Yes, no direct evidence marks Pushkin’s 1827 narrative poem “The Gypsies (Цыгaны)” as inspiration for Mérimée’s 1845 novella “Carmen,” and the plots are not carbon copies despite the centrality of a Romani woman and her obsessive, eventually murderous lover from outside her community. But it is largely agreed that Mérimée read the poem no later than 1840, and he translated it into French seven years after his own story was published. It is plausible to assume some inspiration in theme, setting, and rough characterizations, if not outright adaptation.

“Carmen: remains Mérimée’s most enduring work, and despite its several film adaptations between 1915 and 2003 opera is the medium through which it has become most recognizable. George Bizet’s opéra comique adaptation premiered in 1875 to a lacklustre reception. He died suddenly three months to the day after the premiere, believing his work to be a failure. Opinions, however, soon changed, and “Carmen” remains a cornerstone of the repertoire to this day.

Literary Parallels

Mérimée’s “Carmen” – and its operatic adaptation – bear some notable similarities to the treatment in adaptation of another French literary classic turned operatic mainstay: Dumas fils’ “La dame aux camelias” and Verdi’s “La Traviata.” “Carmen” was written three years before “La dame aux camelias,” and like it is told by a narrator who meets its central characters in some capacity before the full story is relayed or revealed to them. Strikingly, both narrators are outsiders who come into contact with the male protagonist primarily or solely when the female protagonist is dead; their interactions with Carmen and Marguerite Gautier are limited to one evening of fortune-telling and a tour of the recently deceased’s apartments.

Another notable similarity is that both women are societal outcasts – Carmen for her race and Marguerite for her profession. Indeed, Mérimée’s nameless narrator notes that “here is a certain charm about finding one’s self in close proximity to a dangerous being, especially when one feels the being in question to be gentle and tame.” The dead women’s lovers – both from lower nobility within their nation’s orthodox social hierarchies, both perceived as corrupted by their association with their former paramours – are the ones left to give their version of the story.

In a way, this external narrator acts as a frame to explore more “scandalous” subject matter, though the empathy extended Marguerite is not quite mirrored in Mérimée’s casual racism and fetishization. His epilogue in particular ages extremely poorly, as he pseudo-scientifically attempts to characterize Romani and traveler peoples as exotic, other, and inferior (it should also be noted that Pushkin’s poem reads as the kinder, more open-minded text today). The novel certainly leaves a bitter taste today, and Bizet’s opera is rooted in similar racist tropes. However, the removal of its most egregious slurs and descriptors in a dialogue-based tale make the story ripe for re-evaluation and a stronger dramatic blueprint.

A Living World

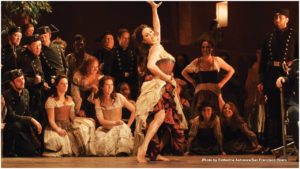

Bizet, like Verdi and opera’s other great dramatic minds, brilliantly brings to life his writer’s world through a large and diverse cast of characters. The opera opens with the dragoons, a children’s chorus, and the cigarette factory women introducing themselves in turn, creating a bustling Seville without unnecessary exposition.

But among these, Carmen and Don José are the only two directly lifted from Mérimée’s work. The matador Escamillo is roughly shaped from Lucas, a picador (lower rank of bullfighter) found in the novel. However, Escamillo’s promotion in status and role size allows Bizet to remove Carmen’s common-law husband entirely, focusing on one central romantic rival rather than two. And while Don José triumphs in the knife fight against Carmen’s husband, killing him, the knife fight in Bizet’s Act three ends on a more ambiguous, antagonistic note. The climatic standoff between scorned man and rebellious woman thus gains a more sinister significance – with one extra humiliation, the stakes are higher.

As well as removing and combining characters to narrow focus on Don José’s all-consuming passion for Carmen, he adds several women to contextualize Carmen’s society – and the one Don José leaves behind. Carmen is joined by Frasquita and Mercédès, two Romani smuggling companions who add context to Carmen’s belief in her immutable fate. In the novel, any such female companions are unmentioned and unnamed.

Don José is given Micaëla, a young lady from his Basque village who has his mother’s blessing for his hand in marriage. While similarly missing in Mérimée, Micaëla physicalizes the women Don José finds comfortable from his home, when he admits that he “didn’t believe in any pretty girls who hadn’t blue skirts and long plaits of hair falling on their shoulders.” Carmen is an immediate contrast, threat, and temptation.

By removing characters that add plots unnecessary to the central theme and driving stage action, and by adding others that vivify Carmen’s and Don José’s clashing worlds, Bizet creates a world that lives and breathes on its own. It does not need a narrator or social commentator to enthral.

Carmen’s Reinvention

In the first five entries of Page to Opera Stage, the source material still largely stands on its own today. In today’s – the sixth – time has not been as kind. “Carmen” may have aged the most poorly on its own merits (or lack thereof, in its regressive racial otherings), but tracing the origins of a beloved opera from a Russian poem, through a French novella, and to stages all over the world. Bizet’s opera has been reframed in various historical and political context (see Sir Richard Eyre’s Franco-era Metropolitan Opera production), with varying degrees of realism (see Barrie Kosky’s work at the Royal Opera House), and varying sympathies granted its central antiheroic couple.

The tale of love, jealousy, and murder will no doubt mirror new anxieties and mine new truths as future generations remake “Carmen” in their own images.

Categories

Special Features