Opéra National de Paris 2022-23 Review: Carmen (Cast B)

By João Marcos CopertinoParis Opera’s “Carmen” staging was sold as the same production staged last November, yet everything was different. Adding one or two gestures here and there can almost completely change the characters’ psychology.

Calixto Bieito’s staging remains impressive and provocative. He emphasizes the importance of true meaning to the detriment of the exploitation of empty forms. The impact of such a turn leads to strong reactions from the audience. When meaning is in question on the stage, things can get ugly.

Bieito’s “Carmen” mocks everything and everyone. It is a virulent critique of authoritarianism and capitalism, showing how national symbols become devoid of meaning while the “other”—i.e., the non-white male body—is subordinated. Set in Franco’s Spain, things that once might have had meaning are now just caricatures of a nation meant to ignite summer tourism: form without meaning.

Bullfighting, for Bieito, isn’t a show without meaning, so he brings it to the center of his “Carmen,” where the titular character finds meaning when facing her death in the shape of a bullfight.

The Toreador stares down death for pleasure (“Pour plaisirs ils ont les combats”), yet he simultaneously brings pleasure. At the very start of the opera, an actor cries out: “Love is like death.” As cultural critic and polymath Wayne Koestenbaum pointed out, “L’amour t’attend” sounds very close to “La mort t’attend” when sung.

The possibility of onstage transcendence exists because the bullfighting arena is one of the few theaters in which actual death is normalized. Blended with elaborate form, death gives “Carmen” an inescapable sense of meaning. In the second entr’acte, Bieito’s direction calls for a man to undress. The point is not necessarily about the exhibition of the sculpted male body—a spectacle he exploits elsewhere. Instead, it is a tender moment in which a soldier divests himself of his army clothes and the symbolic protection of the patriarchal state to face death—or the bull—with nothing but the vulnerable flesh of his naked body. It’s honest.

If the core of bullfighting glorifies the universal human self and the fall of the other, then Carmen cannot be the bullfighter of the story. Instead, she is the idiosyncratic “other” right from the start. As the opera progresses, the audience increasingly identifies with Carmen even as it becomes evident that “La mort”/”L’amour” awaits at the end of the performance. Her death is the most sincere and meaningful moment in the staging while also being the most theatrically choreographed moment of the show. The implication is perhaps clear. For Bieito, bullfighting is where form and meaning meet—the last realm where gestures are still vital and have not been degraded into stereotypical forms.

A Superb Cast

Clémentine Margaine has one of the most emblematic mezzo-sopranos voices of our day. Her voice is highly uniform in all registers and has excellent projection within Bastille’s hard acoustics. Although these two qualities have often been noted, Margaine’s Carmen is memorable for other reasons. She has great control of her vibrato, providing the role with many nuances, and she easily transitioned from an almost non-vibrato phrase at the end of Act two (“Là-bas, là-bas dans la montagne”) to the dramatic and vibrant tones of the “letter trio” in Act three. Also remarkable was her attention to the cues from the orchestra and how she blended her voice with that of the instruments. In particular, her interaction with the cellos was interesting all night long.

The mezzo’s presence was highly fluid. Margaine has been involved in this production for over five years; hence, she is perfectly comfortable in the role and Bieito’s milieu. The mundaneness of Carmen’s daily life at the margins of the system remains and makes her more vulnerable physically than usual in interpretations of the role. The vulnerability seems less to display weakness than the character’s boldness.

Nicole Car had a refreshing take on Micaëla. Her voice possesses darker colors than most sopranos singing the role, a quality she exploits to make Micaëla an entitled woman. Micaëla’s sweetness can be seen in her mothering Don José. Both Wayne Koestenbaum, in his seminal “Queen’s Throat,” and director Emma Dante have stressed that side of the character. Car, however, revealed the problems of focusing on that facet of the character. Micaëla is a good girl, but she resents not being the center of attention. Car also makes the character way more moralistic than usually portrayed, and her spitting at Carmen at the end of Act three was meant to feel like an elitist act of aggression. It thus seemed like another instance of “othering” the protagonist while also making her—the conservative girl—the correct ideal of womanhood.

Impressively, Car constructed such a big twist on Micaëla with her vocals. The soprano stressed the powerfulness of her upper middle range, showing how much strength she had within. Her confrontation with the guards in Act one showed command beyond any naiveté or class shyness, mimicking the inflections of the soldier chorus and Moralès. If anything, Car makes Micaëla entitled.

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo’s Escamillo is highly charismatic. The bullfighter is beloved, and D’Arcangelo is perfectly comfortable in his skin. Some costume changes from the fall helped, and though D’Arcangelo’s costume is still gray, it’s a lighter shade, making him stand out against a mostly black backdrop. D’Arcangelo is a skilled actor who is very good at connecting his stage movements to his vocal inflections, making the audience “hear” his movements in a brilliant way. That said, his perfectly audible voice had less projection than usual. And Bieito’s staging cut some dialogue that D’Arcangelo would have shined when delivering his lines.

But…

Unfortunately, Joseph Calleja struggled as Don José. Calleja has been one of the greatest tenors of the past decade, and, to this reviewer’s mind, what he has forgotten about music is more than most tenors will ever learn. Therefore, I have much respect for his work, but he was far from sounding his best. He still has one of the most roaring tenor voices I have ever heard. His recognizable timber, caprine in the best meaning of the word—still mesmerizes. While the Paris audience showed much affection for him, Calleja struggled with all the notes in his upper register. Anything higher than a G sounded opaque and hoarse—very different from his performance as Cavaradossi in the fall of 2022.

Calleja controls his voice well in both pianos and fortes, but there is little nuance in the middle. In his duet with Micaëla, Calleja’s “Ma mére, je la vois” harmonized with Micaëla’s entry with the melodic theme (“Sa mère, il la revoit”) but was so loud that Nicole Car’s potent instrument was barely audible. Perhaps someone needed to tell him to tone it down.

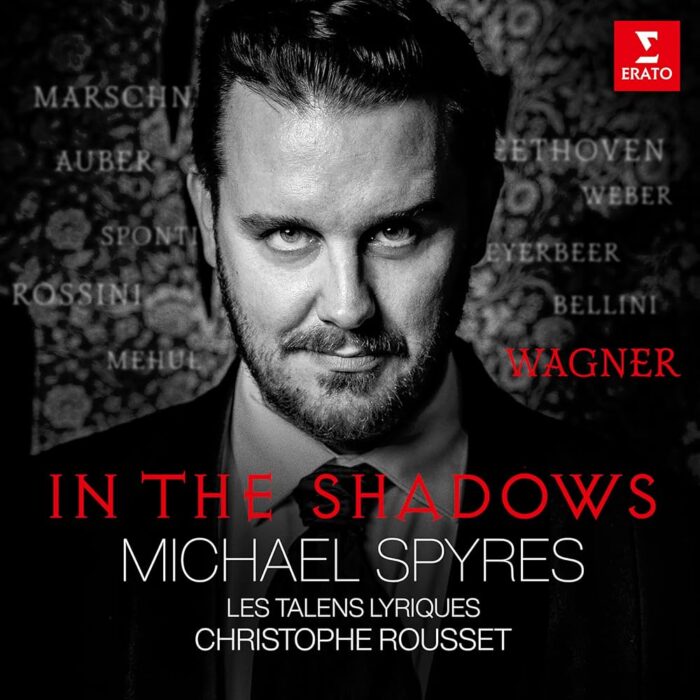

Most of the cast’s great acting also clarified how much Calleja could improve his scenic presence. Not that he was bad, but the average in the cast was very high. Like his voice, his Don José had two main modes: happy or violent, with nothing in between. There wasn’t a journey of emotions. Nonetheless, his violent moments were raw. Indeed, unlike baritenor Michael Spyres in the fall, Calleja aimed for expressions of physical violence that made Don José a caricature of a failing patriarch and resulted in taking away much of the character’s psychology.

Tomasz Kumiega seemed much more comfortable playing Moralès, both scenically and vocally, than in the fall production. Guilhem Worms’s Zuniga is extremely compelling scenically, and Andrea Cueva Molnar, as Fasquita, still produces striking high notes. The consistently good Adèle Charvet improved her approach to the lower register required by Mercédès. I do still find the belligerent dynamic between the two uncalled for.

Finally, maestro Fabien Gabel showed more familiarity with the score, with his tempi faster than in the fall. He also had better control of the orchestra, whose wall of sound overpowered voices last autumn. There were some rhythmic imprecisions, mainly when associated with Bieito’s coupes de thêatre. The orchestra had beautiful moments. The cello solo, with Escamillo’s theme at the end of Act three, played by Aurélien Sabouret, was excellent. Overall, it was a good night at the opera.