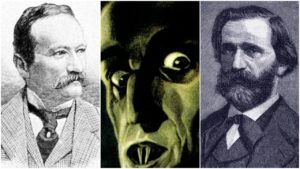

Opera Meets Film: The Strange History of Operatic Passages in Erdmann’s Score for Murnau’s Iconic ‘Nosferatu’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Murnau’s classic “Nosferatu.”

A few months back we focused on how Werner Herzog employed operatic excerpts, specifically from Wagner’s Ring, for his adaptation of “Nosferatu the Vampyre,” a remake of Murnau’s timeless masterpiece from 1922.

And while Herzog’s choices on operatic selections do not necessarily have anything to do with Murnau’s film, it is interesting to note that there is a thread of operatic use in both of them. In fact, there are operatic excerpts in one narrative instance of BOTH films – the arrival of the central hero (Thomas in Murnau, Jonathan in Herzog) at Count Orlok / Dracula’s castle.

But before we get into that we must contextualize a bit on Murnau’s film and its score, originally composed by Hans Erdmann.

Murnau’s film was an unauthorized version of Bram Stoker’s famed novel and despite attempts to conceal this fact, lawsuits by Stoker’s wife resulted in an order to destroy all copies of the film. One copy however had already been distributed worldwide and it is thanks to this bit of luck that this perennial classic remains.

However, the same could not be said for the score by Erdmann with the full score only heard during the film’s original world premiere. Only 40 minutes of music of the 95 minute film remained and they were contained with a Suite. Since then research has allowed for several reconstructions by musicologists and composers. Among these are Gillian Anderson, who realized the reconstruction of the score with the help of U.S. composer James Kessler; this one was released in a 1995 recording; her work is said to be the most faithful to Erdmann’s intentions. And others came from Brendt Heller and James Bernard. In all cases, the composers had to find ways to fill in gaps that would either have used repeated sections or other pieces of music that were altogether lost.

One of the fun facts is that we do know that Erdmann’s original score utilized an adaptation of the overture from Heinrich Marschner’s opera “Der Vampyr” so right off the bat, there was an inherent operatic connection.

But the really interesting “arrangement” of the score comes from Heller and that is where our attention will now turn. Heller’s reconstruction premiered in 1984 at the Berlin Film Festival (a copyright for this version came in 1994) and is the only one sanctioned by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung; it is the one used exclusively for most home video releases (including the version streaming on the Criterion Channel). Heller did away with the Maschner excerpt altogether and several passages from a Suite used as the basis for Erdmann’s arrangement. He also interpolates a lot of music from many other composers, making the score more of a pastiche rather than a faithful restoration of Erdmann’s original intent.

Among the pieces he interpolates are two opera passages from Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera” and one from Boito’s “Mefistofele,” both of them related thematically and visually.

“Un Ballo’s” first passage comes about 24 minutes into the film when Thomas arrives at Nosferatu’s castle. In this instance, we hear the bass sounds of Ulrica’s famed aria from “Re dell’abisso, affrettati.” The effect is quite palpable with the dark theme, pulsating accompaniment, and well-placed dissonances adding to the sense of dread that surrounds Count Orlok’s palace. Act one of the film ends with an emphatic chord that suggests the danger of the situation Thomas has now arrived at.

About five minutes later we hear the opening bars of the very same opera as Thomas writes to his beloved Ellen and tells her of a mosquito bite and his strange dreams. This passage in Verdi’s opera offers up a nice choral contrast between the Governor / King’s loyal servants and the rumbling of the conspirators. And here, in the context of this film that same contrast is drawn between the sunny exterior and joy Thomas feels about writing to Ellen with the insidious danger he is in; the conspiratorial bass motif also draws attention to the mosquito bites he mentions (they aren’t mosquito bites).

Whether or not Heller intended a deeper symbolic link between the score for Nosferatu and Verdi’s “Un Ballo” is unknown and I won’t investigate further, especially when considering he interpolated a slew of other unrelated pieces. The farthest conjecture I could is that Verdi’s opera deals with unmasking characters’ identities and often finding that the surface has nothing to do with what lies beneath; we see that with Ulrica’s relationship with Gustavo / Riccardo and then in the love triangle, the conspirators and their true identities, and then, ultimately, in the final ball in the opera. Orlok / Dracula, of course, is presented as a benevolent man of wealth who reveals himself as a plague.

But one can definitely not ignore Heller’s other selection – that of “Mefistofele” by Boito.

As the ship Orlok sails on heads toward Thomas’ hometown, we see an intertitle remark about a plague breaking out in Transylvania. Under this, we hear the introduction of Margherita’s famed aria “E’ mia madre addormentata.” It’s a brief passage and the high point of the melodic expression comes over a shot of the ship on the water, but creates a conflicted rush of urgency and calm at once; the impending tragedy seems to loom large. From there, it cuts to a shot of Thomas trying to make his way back home as the single woodwind plays out the end of the introductory passage. “Mefistofele,” of course is the story of Faust and his relationship with the demon Mefistofele who he pledges his soul to. In the midst of this relationship, Faust strikes up a romance with Margherita, who he leaves pregnant and broken. She drowns the infant and then ends up dying by the end of the opera’s third Act.

In the context of this film, the parallels are quite potent with Count Orlok being the placeholder for the devil and Thomas and Ellen playing the roles of Faust and Margherita. The water symbolism ties in appropriately to the drowning of Faust and Margherita’s child and the suggestion that Thomas’ selling property to Nosferatu (literally making a pact) will result in a similar tragedy not only for the two, but for their whole town.

As one final aside, it is worth noting that Thomas’ journey to and from Transylvania is highlighted by these operatic passages; as is Dracula’s journey to Thomas’ hometown. And this is where the interesting link comes in with Herzog’s film (Herzog’s film was released in 1979). In Herzog’s film we hear the “Das Rheingold” prelude play out during Jonathan’s journey to Dracula’s castle AND again when Dracula is making his way to Jonathan’s hometown and then again when he travels to his new hideout. Given the timelines of Heller’s reconstruction of Erdmann’s score, it begs the question of whether this is a mere coincidence.

Categories

Opera Meets Film