Opera Meets Film: The Emotional & Metaphorical Use of Wagner’s ‘Tannhaüser’ in Jules Dassin’s ‘Brute Force’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Jules Dassin’s “Brute Force.”

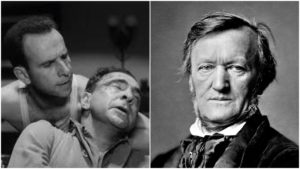

As Alex Ross notes in his book “Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music,” Hollywood in the mid-20th century would often employ Wagner’s music to depict “sadists and cold-blooded killers.” He immediately points to Jules Dassin’s masterpiece “Brute Force” and its major turning point when Captain Munsey tortures one of the inmates to get information on when Collins and his gang plan on making their great escape.

While Ross’ assertion of Wagner being used as a metaphorical to fascism in the context of the film, there is much to glean from the specific choice of music that Dassin picks. In our collective conscience, the Nazi regime’s atrocities and horrors ring most visibly and Hitler’s own passion for the master of Bayreuth undeniably makes the connection. But Dassin doesn’t opt for any of Wagner’s most energetic or potent outbursts in the torture sequence. He doesn’t push for the oppressive storm sequence that opens “Die Walküre,” the tragic march that accompanies Siegfried’s death, or Klingsor’s demonic music from “Parsifal.”

He opts for the opening of the overture from “Tannhäuser,” specifically the music linked to the pilgrims.

The music commences as Miller is brought to Munsey’s office. We hear the opening strains of the overture delicately, the sublime music growing louder as Miller gets closer to Munsey’s office. A brief scene between Munsey and another officer sets up the fact that Miller has been brought to him. Munsey, who is cleaning off a rifle, stands at the far end of the room in a tanktop. The music continues as Munsey, surprised, asks about Miller’s interest in heading to the drain pipe (where Collins and his men have been working and preparing their escape).

Notice the contrast that the music creates for this scene right from the go. “Tannhäuser’s” overture does not suggest anything in the way of danger. Those unfamiliar with the music would be taken away by its relaxing nature in fact. But the first image we see of Munsey is with a gun, which immediately creates all sorts of cognitive dissonance and establishes the tension for the scene. What’s more, the sustained music is in direct contrast to how music has been used throughout this film – sparingly. Something feels off for sure.

Munsey puts the gun away and Miller is brought it. We get an insert of the record player to establish where Wagner’s music is coming from. Now we know it is a diegetic part of the scene and establishes Munsey as a Wagner-loving prison officer; the metaphor for fascism is made overt in this very moment.

But what happens next is the true masterstroke of the scene. As the tension between Miller and Munsey builds, the music ratchets up to fit Munsey’s increasingly monstrous actions. But instead of building to the triumphant march, the music is twisted into something else, further dovetailing with Munsey’s increasingly tyrannical means. It all builds to a Wagnerian crescendo as the camera dollies into a low-angle closeup of Munsey striking Miller from behind. Then we cut to a shot of the officers outside, unable to ignore the beating Miller is receiving.

When Munsey stops beating Miller and starts to question him again, we return to recognizable music from Wagner’s fifth opera. We get another cut to the music before some final questioning from Munsey brings the scene to a close; notice the bookending insert of the record player and Munsey’s abruptly turning the music off once the torture has ended.

Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” overture is music of the most sublime order, but here Dassin, in addition to using it as a metaphorical means of connecting Munsey to fascism, also explores its dramatic potential through counterpointing and eventually transforming it with the horrific events unfolding before our eyes.

Categories

Opera Meets Film