Opera Meets Film: How Yohan Manca’s ‘Mes Frères et Moi’ Explores Opera’s Healing & Liberating Power

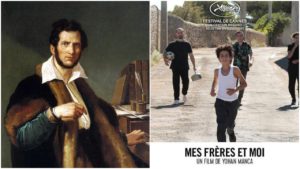

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features “Mes Frères et Moi”—”My Brothers and I”—directed by Yohan Manca and starring Maël Rouin Berrandou, Judith Chemla and Dali Benssalah.

“My Brothers and I” opens in the south of France with a young boy watching the world as it passes him by. 14-year-old Nour—played by Maël Rouin Berrandou—lives in a public housing project with his four brothers. The brothers are all working to keep their comatose mother alive, and while he dreams of something better than what he has, the likelihood of the family going anywhere is at best minimal, and most likely zero.

Nour has to settle for what life has given him, which is an existence at the mercy of his brothers. His only solace is in a recording of “Una furtiva lagrima” by Giuseppe di Stefano, which he listens to, over and over.

One day while on a job, painting at a school, Nour hears some music: Pavarotti singing “Nessun Dorma,” concluding with his iconic “Vincerò.” Nour eavesdrops and comes face-to-face with a music class. He is invited to take part by the teacher, Sarah, played by Judith Chemla. Nour initially rejects the invitation out of a fear of being ostracised by a male-dominated world that views this pursuit as not becoming of his gender: to emphasize this point, the class consists exclusively of girls. But Nour slowly, yet surely, becomes a major part of the class and learns not only to sing his beloved “Una furtiva lagrima,” but eventually even sings the Brindisi from “La Traviata” alongside Sarah.

There is no denying it: opera in “My Brothers and I” is seen as a liberating force, one capable of not only uniting people, but breaking through boundaries and providing healing.

Early on in the film Nour is heard listening and singing to “Una furtiva lagrima,” which he later reveals to be the piece that his father sang to woo his mother. As the film progresses, we learn that it is his goal to sing this piece in the hopes of reviving his mother, who is in a coma with little hope for survival. With this new light shed we see how his interest in opera is tethered to its past significance in his life and, by extension, his current trauma.

At the climax of the film he attempts to use this piece to revive his mother. After his brothers steal her back from the hospital, Nour sings for her. And it seems that, for a moment, the miracle indeed happens. His mother moves: or so he says. When he calls in his brothers to witness it again, nothing happens, and in a simultaneously humorous and tragic wide shot of the four of them, each one leaves one at a time, leaving Nour all alone with his mother. In the end he could not save her with his music.

One might wonder about “Una furtiva lagrima” as the musical centerpiece of the film. It is nostalgic, set in a minor key, and it explores a character getting what he wants but also thinking it is too late. Nemorino sings about seeing Adina cry, realizing that she does indeed love him: but now that he is off to join the army, he has no hopes of being with her. In many ways, the piece ties in with Nour’s own assessment of his situation with his mother: he knows this piece means everything to her, yet he has no hopes of being with her again. It is too late.

But the film ultimately settles on that not being the point at all. The music was never meant to save his mother.

Enter Sarah’s character. Our introduction to her comes via her silently singing along to Maria Callas’ interpretation of the Habanera from “Carmen.” Her pizzazz and enthusiasm entertains the girls in her class and even Nour. She immediately establishes herself as exciting, unique, and full of life. Eventually, during a session with Nour, she reveals herself to not just be a music teacher, but a performer in her own right, and invites Nour to see her perform “La Traviata” onstage. We finally see this in the film’s epilogue. The film depicts the performance through Nour’s eyes, focusing specifically on her performance of “Sempre libera.” This might be the moment where director Yohan Manca is most explicit in his exploration of what opera and art mean in his story, but it also serves as a nice conclusion to Sarah’s arc: how she has guided and transformed Nour through her belief in him.

Sarah takes Nour on as a student in a rather idiosyncratic fashion. Unlike the girls in her class, he isn’t properly matriculated and has a tendency to miss classes. Yet, even after kicking him out for his absenteeism, she continues to guide him and later in the film defends him from his eldest brother’s accusations that singing is emasculating him. When police officers raid the brothers’ home, she is there to fight them in the hopes of saving a small piano in Nour’s room, a symbol of the importance of music in his life: something which is being constantly undermined or outright violated by others.

It is this championing of him that makes him realize, at the film’s end, that it is time for him to let go. In a poignant moment we hear “Una furtiva lagrima” one last time at the funeral for Nour’s mother. This time, however, Nour doesn’t attempt to sing. The accompaniment plays on alone as the family moves away. In a concluding scene on the beach—the film opens on the beach as well—Nour tells the audience that it is time for them to go. In this way, opera plays a unique role in Nour’s life: both tying him to the past, yet ultimately liberating him and his family from its trauma.

Categories

Opera Meets Film