Opera Meets Film: How Wagner’s ‘Das Rheingold’ Explores David’s Awakening in ‘Alien: Covenant’

By John Vandevert“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features “Alien: Covenant.”

Since the dawn of time, human-kind has been devoted to understanding its position in the cosmic vastness and uncovering what exactly lies beyond the realm of the supposedly finite, living fabric. So dedicated were our ancestors to unmasking the unreal from the real that the earliest-known “holy place,” is said to have been created around 9,000 B.C., this primitive “temple being called ‘“Gobekli Tepe.” The fairly large complex, now only ruins, was said to have been dedicated to primordial worship of animal gods of the after-life, while some of the first creation-based mythoi, namely the Sumerian great-flood chronicle “The Eridu Genesis” and the Babelyonian epic “Enuma Elish,” are appraised to have been authored around 1,200-1,900 B.C.

Evidently, the appeal of uncovering our biological origins and organic development on Earth has served as the incipient catalyst for a plurality of secular and sacred belief systems, mythologies and inherited traditions, even doctrinal credos by which man, the once unstained creation crafted “in his own image,” sought to formally rationalize the boundless irrational. By intellectualizing the supposed “supernatural,” the collective “we’”were attempting to generate a feasible path forward which could explain the innumerable idiosyncrasies of the human condition and surrounding world, thereby staving off existential instability and producing a working, hierarchical scala naturae where every natural object and experience could neatly fit into a particular strata.

However, alongside the many proposed, evolutionary ancestries like Hinduism’s Trinity of Creation [Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva] and Sumerian-Akkadian stories of man’s conception from spilled blood of “Alla-Gods,” what was ultimately spawned was not submissive compliance but the direct opposite, a desire to know, lust to copy, and fervent ambition to control.

Here is where Ridley Scott’s 2017 film, “Alien: Covenant,” comes into play, a film about a disconcertingly plausible, fictional investigation into the origin of man and its biological manifestation on Earth. Ultimately, humanity is accredited to a race of colossal, opalescent humanoid’s called “Engineers” whose own corporeality is never specified but whose ability to seed life is granted from a portentous black fluid, “Primordial ooze,” gained via a crystal sourced from an ostensibly higher intelligence. With an obdurate arrogance, the film dissolves man’s naive assertion of divine omnipotence and dismantles our religious fidelity to a “Natural Order,” replacing in its wake the uncouth alternative that, in fictional fact, the modern man is the result not of Darwinian natural selection, but artificially mandated direction [Orthogenetic evolution].

Yet, for as great as our fabricated heritage may be, the mortal human is still unavoidably susceptible to the ravages of time and subsequent bodily decomposition, no matter how exceptional the intellect, seductive the body, or even ruthless the constitution. In the film’s opening scene, Peter Weyland, tech-ologarch and founder of Weyland Industries, the company responsible for constructing the first “living” AI [David], is seen accompanied by his “son” David in an expansive, stark-white observation hall, furnished with nothing more than a Steinway grand piano, a towering imitation of Michelangelo’s “David,” an eccentric, transculturally designed throne by the 20th-c. designer Carlo Bugatti, and the 15th-c. painting by Piero della Francesca depicting communal adulation of baby Christ. Further, as if to punctuate the anthropological hindrance of time when juxtaposed against eternal, synthetic perfection, Weyland and his quickly unraveling God-project David are seen standing interiorly to an exterior Tolkianian terrain, complete with mountainous hills and valleys covered in greenery, and topped with an apprehensive sky, as if Mother Nature is holding her breath, afraid to rain for fear of missing something important.

Now, having laconically set-up the scenery and the character’s direct surroundings, what happens within the scene, namely the presentation of a quintessentially Wagnerian motif by David, only intensifies what E. Granzotto noted as the topos of ‘“doomed Gods,” following in the narrative lineage of Wagner’s Ring Cycle and concurrent Norse mythology. But the question remains, why does this quotation matter, and more importantly, why was Wagner specifically chosen?

Wagnerian Function

In 1852, Wagner published a lengthy, three-part treatise, “Oper und Drama,” where he delineated his opposition to contemporary opera, although in the process describing a personal comprehension of the phenomenological ontology of music. He argued that the operatic artform was being stripped of its faculties for intrepid persuasion, namely that the poetic, “dramatic,” component had been sacrificed for the sake of baseless enjoyment, that the “great one-centred fabric of the Drama’s whole,” was in danger of being lost for good. Curtly summarized in a short, but potent, axiom, “Means of expression (Music) has been made the end, while the End of expression (Drama) has been made a means,” Wagner invited the reader into a necessary dialectic about the self-reflexive relationship of “Word-Speech” and “Tonal-Speech.”

However, this developing reciprocality is only made possible when the “Life-need of the drama” is respected and honored as the true agitator of the intontational framework to which it is prescribed during the act of composition. If this process succeeds, meaning if the “instinctive Will” and its natural pull towards manifestation manages to integrate with “Feeling,” then what is subsequently created is a “Unity of artistic Form,” where every artistic layer is not anymore powerful than the other, the causal nexus of the semiotic membranes creating in-turn a total synthesis [“Gesamtkunstwerk,” or “great united work”].

Ergo, when looking at Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant and its use of a truncated, unassuming excerpt from Wagner’s “Das Rheingold [“Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla”],” it’s easy to overlook its “synthetic” connection to the latent, pugnacious atmosphere which is to burst later in the scene, or the humanistic decorum exhibited by Weyland [“Master” of David] at the growing thought of his creation’s autonomy and “its” own cognitive “Entrance.”

Each attribute, both fugitive and enduring, of the incipient scene holds hermeneutical significance, of which is lost if one ponders too long on the specific factors of “this means X” and “this means Y;” because if one is to conclude that David, the flawless android who was given life only to serve, is indeed “human,” supported by Scott’s own comments, “In the prologue […] David is actually human. He has emotions,” then how can we assume that anything is truly how it wills itself to be taken out of its surrounding factors?

If we follow this investigative throughline, that being that each cinematic object harbors meaning due to its co-relational surroundings, then this initial scene itself could be considered, by way of interpretational license, a Wagnerian operatic equivalent.

In the initial scene, we have seven elements, minus the dialogue and side-table: 1) the blanched, aseptic room itself, 2) the Scandinavian, foreboding landscape, 3) the pristine recreation of Michelangelo’s David, 4) Piero della Francesca’s Nativity, a fascinating case-study in “‘visually-evoked auditory response” or [vEAR], 5) Carlo Bugatti’s idiosyncratic, upholstered ‘throne’ fit for an ego just as ‘unique,’ 6) a Steinway Black Grand which renders Wagner’s quotation ‘anemic,’ and 7) the two characters themselves, embodying the antithetical extremes of man’s pitiful desire to ‘be God’ and to control the progression of linear temporality. Having defined our cast of animate and inanimate “hermeneutical conduits,” borrowing Scott Trip(2012)’s verbiage, when comparing each element to its operatic equivalent the plot thickens, pun very much intended. Commenters on an open-forum website called alien-covenant.com had delineated as such, one user making the comparison of Weyland embodying Wotan, Ruler of the Gods and creator of Valhalla [hall of slain heroes], myself going a step further and considering David an augmented variation of Alberich. the power-hungry dwarf and Ruler of the Nibelungs [race of cave-dwelling dwarfs and original cursers of the Ring, guarded by the subaquatic Rheinmaidens].

David & Alberich

The comparison of David and Alberich goes much deeper, however, as within “The Ring Cycle,” a four-opera epic music-drama charting the narrative of a doomed golden ring which falls into various, volatile dominions until at last being returned to the watery abyss from whence it came. Alberich is one of the few characters who foretell the death of the Gods and the destruction of Valhalla.

Returning to the open-forum website, this collation is expunged in detail, one commenter noting the almost perfect mimetic plot of the movie stating, “Like Alberich, David forsakes his love for Elizabeth to steal the secrets of the Engineers and forge them into the Perfect Lifeform [Xenomorphs];” take note of the word “love” in collaboration with an ostensible “robot,” David’s original design being to serve without the ability to generate sentiments of any kind. However, this assimilation of cinematographic narrative and operatic plot is dually contested in accordance with a diversified pallet of speculations, a different commenter remarking Weyland and David’s similarity to Greek mythological figures Prometheus and Echidna respectfully. The former’s identity is well-known as the fallen Titan who bestowed fire unto man in hopes to aid in their continuous development, however resulting instead in his eternal damnation chained to a mountain to suffer at the beak of an enlarged eagle.

But the comparison is richer than superficial surveys as Prometheus, according to the narrative “The Theogony” of 8th c. poet Hesiod, summarized by CSUN’s J. P. Adams, dictates the tragic hero as the primary “Benefactor of Humanity,” deposing Zeus of that lofty title, who is responsible for bringing ‘cleverness, intelligence, technology, religious practices [and] culture’ to humanity without remorse.

Likewise, if we venture into the first of three plays by the 6th c. dramatic playwright Aeschylus, namely “PROMETHEUS BOUND,” we are greeted with the real reason Prometheus wanted to save humanity: “None of the gods objected to his plan [to wipe out humanity] except for me. I was the only one who had the courage. So I saved those creatures from destruction and a trip to Hades.”

Thus, David could be seen as the polemic “hero” figure, albeit not yet fully developed [or indeed developed but not yet disclosed to the viewer] who, as seen farther into the film, is responsible for the creation of the perfect organism [Xenomorph], a rather uncouth alternative to Prometheus’s gift of fire but still a “present” none of the less. This tinkering with the creational process and humanity’s natural evolution subliminally permeates this beginning scene and the music chosen by David at the behest of Weyland only strengthens a churning substructure present without the presence of music, that is the pursuit of total control of Nature in all its manifestations. However, this fatal motive, perhaps labeled the “Faustian motif” after Goethe’s own caustic depiction of “Man as God,” is made mockingly palpable by the narrative, sonic inclusion and thus the “Entrance into Valhalla” fragment is less an additional, hermeneutic layer and more akin to a finally audible whisper previously heard but not fully addressed.

Wagner’s own statements regarding the role of the orchestra allude to the position of music as a secondary support system to the greater, expressive whole, its function being considered a “compensatory organ for preserving the Unity of Expression.” Simply put, the instrumental orchestration does the emotive “filling-in” alongside the text and its respective tone-based structures, subsequently allowing a fluid continuation of meaning to percolate throughout the work, as a result Wagner notes, the “awakened Feeling remains in its uplifted mood.”

When David sat at the piano and contemplated with his cybernetic psyche which piece to perform for his “Master,” I fathomed a verticalistic orientation to the composition I will admit but I had not considered Wagner as the chosen repertoire. Nevertheless, once the majestic, immortal sonorities gestated by the untainted keys, played by relatively aged hands [a paradox no?], sprang from their stagnant cradle, Wagner’s comprehension of orchestrally discharged “equalizing” became almost inevitable. The scene changed permanently, as the incessant, background white noise lacking any type of stimulation, masking not only Weyland’s distrust of his perfect “son” but David’s growing independence, was inescapably transformed. The conscious fears of kin usurping their cradle became manifested and an obliviousness to one’s own demise became the new noise. David played Wagner but Weyland had no idea why.

Deep Dive into Scene 4

This rationale is not subjugated to the interpretational realm only, as referencing “Das Rheingold’s plot,” specifically Scene Four from whence the musical quotation was derived, reveals the exact same narrative structure as its cinematic alternative, albeit wrapped in fine, intonational clothing rather than enigmatic moviedom.

(Briefly comprehending the relatively linear plot of Das Rheingold (read a plot summary of the work here) only promotes greater competency and clarity in understanding the multifarious coatings of collaborative depth to which this opening scene supports. Whereas in other, blockbuster, sci-fi thrillers like Red Planet (2000) and A Sound of Thunder (2005), both considered Box-Office failures, where the musical score served less the role of totalistic storyteller and vessel for premonitory despondency and more aligned with in-moment gesturalism and typically superficial sonic-painting, in the void of sonic stimuli Ridley Scott used a [purposefully] incomplete quotation from the opera thus giving a voice to the palpable polemic of “capitalism and the exploitation of nature.” Ergo, the, albeit brief, musical scoring was not simply auditory filler which was superficially responsible for inducing a quicker heart rate, an overactive nervous system, subversive fear, or even outright disgust, rather its effect is only deductible when the listener knows what is being heard and furthermore, what is being implied. Ridley Scott chose to make the audience member cognitively exercise in order to infer empirical understanding, appealing to what 20th c. Biophysicist Aaron Klug aptly called and which is heavily applicable here, “the urge to know,” stating further this being, “the best secret weapon of all in the struggle to unravel the workings of the natural world.”)

So let’s head over to Scene Four of “Das Rheingold,” the final and most important scene both operatically and filmwise, where we are now transferred back to the mountain within the vicinity of the Valhalla complex. Wotan and Loge deposit their captured Alberich and present him with an ultimatum, his gold deposit and ring for his liberation, to which he concedes and the golden horde is brought up. However, he asks for the helmet back but is denied, likewise he wants to keep the ring but has it stolen by Wotan who then quickly puts it on his own finger. Here is where the “Curse of the Ring” meets its beginning, as Alberich curses the ring in an ecstatic tirade which, without knowing that once Alberich was free from the ring he admits to feeling “free,” could seem like the tyrannical abuse of an angry troll. But it’s more than that, as Alberich finally realizes the consequences of owning the Ring and wishes for no one to own such a foul invention of supernatural malice. He states, “As its gold gave measureless might, let now its magic deal death to its lord! Its wealth shall yield pleasure to none, to gladden none shall its luster laugh! Care shall consume aye him who doth hold it, and envy gnaw him who holdeth it not!,” wrapping up his tirade by dictating the curse shall never be undone until the ring has returned to its “owner” this malicious creed serving as its period. “But my curse canst thou not flee.”

If this isn’t bad enough, that the natural, resplendent ring submerged under natural covering has been tainted with sorrow, Wotan quickly refused to give up the ring himself, leading to contentious anxiety all around. As the giants begin to leave with Freia because the last remaining piece of gold lies on Wotan’s finger as the equal-exchange rule dictates, Wotan is quickly reminded of the disastrous implications of owning the Ring and surrenders its ownership to the giants. But, in oracular truth, the giants fight among themselves for ownership and Wotan, with the other Gods, are left stupefied by Albericht’s curse come true, that anyone who dares own the Ring shall never know peace and shall meet their untimely demise with quick, unsympathetic justice.

However, it is the concluding moments of Scene Four that forcefully confront the oxymoronic reality of the human belief in an all-knowing, “magnanimous” God in the monotheistic sense, in the polytheistic counterstrain an ethical/moral corruption permeating the Godly facade being a commonplace occurrence. Once the giants have concluded their fight, brother Fasolt being pummeled to death leaving Fafner victorious, the Gods quickly realize the destructive effect of owning the Ring. However, this does not bar Wotan from remaining in possession of it, a particularly salient detail of which should not be forgotten.

To dispel the seemingly insurmountable, atmospheric tensity, Donor [ or Thor] summons a thunderstorm thus, at least momentarily, clearing the air of Alberich’s wretched decree, to which Froh [ or Freyr] matches in turn with producing a brilliantly expansive rainbow. This psychedelic footpath [Bifröst] is considered in Norse mythology the interdimensional connection between the realm of the Gods [Asgard] and the mundane, human realm [Midgard], in other interpretations the land of the living and the dead [Heaven and Underworld], but the key detail to take heed of is that in quite plain speech, this “road” is not naturally occurring and must be synthetically created. The connection between the divine realm and the human world, although manifested by celestial manipulation and kept in check by Gods and Goddesses of various distinctions and merits, is no more natural and “real” than the belief in the Deities themselves.

For example, the supposed existence of a God of Disputes [Baldur] or even more minutely, a comforting Goddess who cares for vulnerable beings [Lofn]. Hence, when deliberating on their supposed power over humanity, it would be wise to likewise consider that these rulers of the proclivities of man are no more “Godly” than the human being creation, negating the presence of their fantastical powers and [by exterior intervention] eternal lifespan. Once Bifröst had been manifested, Wotan, as leader, directs the still perturbed caravan over the threshold and into the realm of Valhalla. However missing from this process is the self-aware trickster God Loge [Loki] who refuses to join the procession. Why? Because, just like the self-aware android David to whom the conniving Weyland so desperately wants to keep subservient and ignorant to his own faculties, Loki comprehends the fallibility of these “all-powerful” Gods and their pitiful pursuit for power at any cost, quite literally resulting in their own demise [“The Ring Cycle’s” conclusion is punctuated by the decimation of Valhalla].

As he deliberates on his own vengeful response to the God’s unethicality, the opera is finished by the sound of echoes emanating from the scorned and betrayed Rheinmaidens, again screaming and writhing in agony and sorrow at the fate of their lost treasure at the unlawful hands of those who were given powers exclusively for righteous duties and not selfish prosperity.

Connections With ‘Covenant’

What is clearly observed is the depth at which this quotation correlates to the opening scene of “Alien: Covenant.” Even the name of the movie itself is a satirical chide of Christian theological conceptions of the pact of God and Man, most notably the passage in Genesis (9:13-16) giving an on-the-nose correlation between Bifröst and its Biblical alternative, “And whenever the rainbow appears in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of every kind that is on the earth.”

When the scene first starts, David is seen inquisitively gazing at Michaelangelo’s towering David, a sculptural testament to man’s wanton desire to produce perfection, this throughline made deeper when considering Michelangelo’s childhood pain of having not been entirely the perfect son [He was not interested in pursuing the family, stone cutting business although eventually, he took it up via stone sculpting].

To counteract this filial deficit, perhaps he aligns his experiences with the main subject, the Biblical hero David who, aided by invisible celestial fortification, is seen gearing up and preparing to fight against the Philistine giant Goliath with nothing but a modest sling and an accompanying stone projectile. In another representational layer present in the beginning of the scene, David’s face is covered up due to his looming stature and skylight placement, masking his pensive visage at his internal dilemma whether or not to fight Goliath, a foe completely overpowering in bodily form.

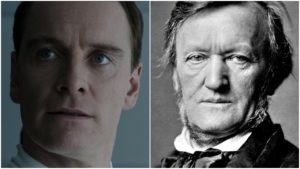

All these factors combined (i.e., Michelangelo’s personal development, David’s agitated introspection, android David’s childlike fascination with the hero figure, concurrent with his burgeoning sentience and Weyland’s growing animosity towards his “creation”), when Weyland asks David, “What is your name?,” the android from that moment on knows he is more than the simple servant, answering “David.” He specifically chooses Wagner, namely “The Entrance into Valhalla” to signify his own journey from passive slave to ambitious Master. David awakens to his humanity, while Weyland sadly loses his own.