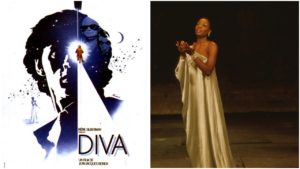

Opera Meets Film: How ‘La Wally’s’ Most Famous Aria Expresses Vast Array of Emotions Throughout ‘Diva’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will hone in on a selection or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perceptions of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Jean-Jacques Beiniex’s “Diva.”

“Diva” is at its core, a movie about the power of music. We could look at the dramatic opera overtures that our hero (or victim) Jules listens to during the work’s opening scenes while he rides around on his moped and how they suggest the fate and doom that will follow him around even when he abandons his vehicle and the music it emits.

We can talk about his intimate scene with Cynthia Hawkins, the soprano he has been admiring from afar, but is now able to engage with on a deeper level when she sings Gounod’s “Ave Maria” for him.

We can talk about Cynthia’s reticence to having her artistry imprisoned and “raped” in a pirated recording. Or the two men on Jules trail trying to get their hands on a pirated recording of Cynthia so they can make some profits.

But all these things are connected by one bigger idea that is expressed by “Ebben? Ne andrò lontana.”

This aria is the heart and soul of the movie not only because it reappears throughout its running time, but how its text and deeper meaning comment on the film.

Let’s start there. “La Wally’s” most iconic piece of music is about leaving a home once beloved.

Leaving behind those that one loves. Being abandoned alone until death. It’s a break from the past.

“There, through the white snow; I will go, I will go alone and far. Through the golden clouds,” the last lines of the aria read, lines which Jules will recite and translate to his friend Alba when he first introduces her to the music. It embodies the loss of his home. The loss of his safety. And even the loss of his innocence throughout the story.

Jules suffers with this music throughout the movie. He also finds his redemption and hope through it.

It all starts in the very first scene when Jules enters a concert hall to watch Cynthia Hawkins live. He illegally records the performance of the aria, trying to capture this moment forever; in his next scene at home, after having stolen Cynthia’s gown, he listens to the piece yet again, lying on the floor slumped over, nostalgia setting in.

It’s quite fascinating listening to the piece in these two contexts. In the opening scene, the general feeling is that of wonder. The camera swoops around the audience, moving toward Cynthia as she sings. Then there is a moment of tension underlined by shots of Jules and two mystery men sitting behind him. Eventually we return to this sense of wonder with the camera bringing us closer to the soprano and then crosscutting with shots of Jules looking on; we feel the intimacy of the moment for Jules.

When we next see him listening, the camera angle wider and his body position vulnerable, the feeling is suddenly of a sadder tone; we feel the longing in him.

One piece of music, despite not changing a single note or accent, is thus able to express a wide range of emotions.

And the film doesn’t stop there. Alba’s first experience is one of wonder yet again, the camera swooping around the small room that a few scenes again was made to feel so claustrophobic with this very music. When Alba takes the record to her lover, he is rather indifferent even though he knows exactly what the music is and who is singing. The spare and bare setting give that same recording a sterile feeling; the camera is static. Again, not one note has changed.

And then the music returns in the film’s final shot when Jules and Cynthia are reunited in the concert hall. She is in front of a bare auditorium but he appears as the only audience member, her recording blasting in the hall. He moves toward her and as they embrace, the camera pulls away from them into an expansive wide shot. The feeling here is a far cry from the wonder or visual virtuosity of the opening scene. And while the closeups of that scene might suggest greater intimacy than a distant wide shot, somehow, we feel the connect between these two with greater intensity.

The music here seems to operate as melancholic of a beautiful connection they enjoyed earlier in the film; it expresses the pain Jules has suffered over the course of the film; and finally, it also feels like pure relief and closure. Where these two characters go from there we do not know. But the music is finally truly able to say goodbye in a way that it simply could not earlier in the narrative.

The true power of the repeated use of this musical excerpt throughout the film is how it reminds us how one piece of music can truly encapsulate a wide range of emotions. Throughout the film, characters constantly try to qualify the art or limit its power. Alba calls opera boring when she first hears it; Jules tries to explain to her why it is far more than she is seeing. The blackmailers see it as a piece of business, looking for any means to profit off of it. For Jules, it is his connection to Cynthia, who conversely doesn’t want anyone to have a piece of her in any way.

In the end, as evidenced by the massive overhead shot, the God’s eye view if you will, music is shown to be far more than anyone can ever imagine.

Categories

Opera Meets Film