Opera Meets Film: How Kon Ichikawa’s Use of ‘Ombra Mai Fu’ Explores Theme in ‘The Makioka Sisters’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Kon Ichikawa’s “The Makioka Sisters.”

“Mono-no aware: the ephemeral nature of beauty – the quietly elated, bittersweet feeling of having been witness to the dazzling circus of life – knowing that none of it can last. It’s basically about being both saddened and appreciative of transience – and also about the relationship between life and death.”

The concept and theme is at the core of many great films from Japan and in a very subtle manner it dominates Kon Ichikawa’s “The Makioka Sisters.”

The 140-minute film details the lives of four sisters as they try to marry off the third while grappling with the rebellious nature of the fourth. Taking place across one year, the film explores how this family is altered completely in that short span, even when there are clear attempts at preserving an unattainable status quo.

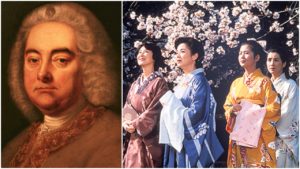

The film has an inevitability to it from its opening scene when the sisters, in a rare scene together, discuss their respective futures. We know that this unity, this togetherness, is not meant to last. That’s furthered in the ensuing sequence when they stare at the cherry blossoms, which both serve as a theme of constant change, but also consistency in the world around them. The blossoms return time and again throughout the film. We see them in the opening shots and we see them change throughout only to revert to their original form in the film’s final shots. Over this cherry-blossom credits sequence, we hear the “Ombra mai fu,” albeit in an 80s electronic mix without a soloist. The famed Handel aria will represent the backbone of the film’s theme.

The aria itself speaks to the beauty of nature and the desire that the tree described in the aria be protected through the challenges that the world endures.

“May thunder, lightning, and storms never disturb your dear peace, nor may you by blowing winds be profaned,” sings Xerxes.

This, no doubt, fits the feelings of the Makioka sisters in their relationship to the cherry blossoms. It is the only moment in the film where we see them at peace. Where we see them united. Nothing in the world around them can disrupt this unity, unlike the rest of the film where they are constantly at odds with one another. In a way, one might surmise that “Ombra mai fu” from Ichikawa’s perspective is a plea for the continued beauty of this family and in the larger context of the film, for the peace and tranquility of the Japan it is expressing. Of course, the film, which is set during pre-World War II Japan, will never retain that “beauty,” with the trauma of the war truly “profaning” the country and its culture.

The aria returns again and again throughout the film, but after the first two iterations, it starts taking on different forms. The backbone of the harmonic structure and certain melodic gestures remain identifiable, but the melody itself becomes increasingly obscured. The aria transforms as the characters transform, and yet there is this sense of continuity in the grander scheme. There is a sense of something bigger happening beyond these small transient lives of the Makioka sisters. In fact, their actions, their changes, will ultimately have little impact in the grander scheme of things.

So when the film comes to a close with the return of the melody in its original form, it hits hard. Played over an image of the four sisters back on their walk through the cherry blossoms, an image that will never take place ever again, we feel the full force of the loss.

The cherry blossoms remain, but the family will never be the same. Neither will Japan.

Categories

Opera Meets Film