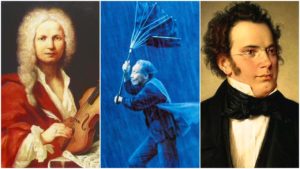

Opera Meets Film: How Akira Kurosawa’s ‘Rhapsody in August’ Expresses its Themes Through Music by Vivaldi & Schubert

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will hone in on a selection or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perceptions of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features opera in Akira Kurosawa’s “Rhapsody in August.”

“Rhapsody in August” is Akira Kurosawa’s penultimate film and it relates the emotional aftermath of those who experienced the atomic bombings of Hiroshima, and specifically, Nagasaki.

The film follows a group of youngsters as they try to convince their elderly grandmother to head to Hawaii to meet a long-lost sibling. But their grandmother seems reticent to do so and throughout the film, her grandchildren come to understand, on some level, the pain that their grandmother had to endure during the second World War.

The depth of understanding commences early in the film when three of the grandchildren head to Nagasaki to purchase some food. They stop by an old school where their grandfather had been when the bomb was dropped and check out a memorial in the school yard. As they approach the charred remains from that day, Vivaldi’s “Stabat Mater” begins to play.

From there, the film launches into perhaps its most fascinating visual sequence in which the three walk around the city to many of the locations that had been affected by the bombing. First we see a montage of several charred statue heads, a stark reminder of the destruction caused. From there it progresses to several memorials and gifts presented to Japan in the aftermath of the bombing, before eventually the closeups of these tokens transform into closeups of tourists.

It ends with the children on the bus, ponder what they have experienced, as if the ghosts of the past linger in the air.

This of course is the result of the “Stabat Mater’s” own haunting nature. And while you definitely feel this marriage of image and sound, Kurosawa is up to something else as well.

The master of using musical counterpoint in his films his choice to showcase the transition from tragic statues to gifts to tourists also emphasizes the fact that for most people, this dark chapter in history is nothing more than that – a chapter.

“For most people, the atomic bomb is something that happened once upon a time,” says one of the children.

The final images of the montage drive this home, showcasing young children, and eventually the closeup of a toddler, all surrounded by pigeons that fly away. The youngest generation will have as much understanding and attachment to this place as the birds do – none at all.

A return later to the same sight, this time with the American relative Clark, sparks the return of Vivaldi’s music for a brief moment, emphasizing the ghosts of the past once again. The fact that Kurosawa returns to this piece in the credits emphasizes his desire to link the audience’s final thoughts of the film with that particular development in the story – he’s almost urging the audience to REMEMBER the tragedy of the past so as to avoid repeating it.

And while the “Stabat Mater” is undeniably the most haunting piece of music used in the film, there is yet another that becomes, perhaps, more crucial structurally and even thematically – Schubert’s “Heidenröselein.”

The piece pops up throughout the film as a leitmotif of youthful vigor. The text of the piece relates a lone rose in a field and the fascination it provided for an onlooking boy. The piece is initially connected with the children as it props up as they are enjoying some fun and games and is later performed by them as a group. It immediately seems to suggest the blooming of youth and its hope for the future.

During a memorial scene for those that passed during the bombing on August 9, we hear its unique rhythm echoed in the chant of those involved in the ceremony; it isn’t an exact match, but it’s hauntingly similar. It is no coincidence that in this very scene, Kurosawa follows a group of ants on an extreme telephoto lens up the stems of a flower, eventually revealing it to be the lone rose in the meadow.

The piece then returns in the film’s grand finale, a sequence of images that matches the potency of the “Stabat Mater” montage. This time, Kane, the grandmother, is seemingly reliving the horrors of the night the bomb was dropped. As she walks through the storm toward Nagasaki, her family running after her, her umbrella pops open and then we hear the Schubert song return in a chorus of children, suggesting that it is Kane, not them, who is the lone rose in the meadow. Her memory, her ability to connect to that horrific yet crucial moment in time, makes her important. And what’s more, like that rose, she can only survive if her lessons are learned by the coming generations, in this case, her grandchildren, who are identified with this very song.

But whether or not they will ever truly learn those lessons is left ambiguous by the final montage of images. As Kane continues walking through the storm with the umbrella unfolded like a rose, slow-motion shots of her pursuing family members see them trip and fall in trying to catch her. And as the film ends, there is no indication that they may ever catch up to her.

This is the latest and final entry in a series that focuses on how the films of Akira Kurosawa uses opera. Check out our entries on “Stray Dog” and “One Wonderful Sunday.”

Categories

Opera Meets Film