Opera Meets Film: Fiction Meets Fairytale In Henry Cass’ ‘The Glass Mountain’

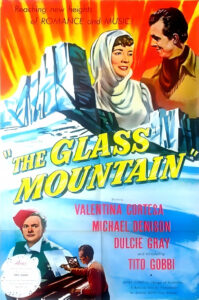

By John VandevertThe idea of putting a movie inside of movie isn’t new, just look at films like “Matinee” (1993) and “The Stunt Man” (1980). But what about an opera inside an opera-based film? This is also not new. For example, the 1947 British film, “Take My Life.” For British director Henry Cass, however, the idea was realized in his 1949 film, “The Glass Mountain.” Starring operatic royalty like Tito Gobbi and Elena Rizzieri, the film described the fated story of a composer, his wife, and his affair with another woman.

Considered to be “solidly directed” with “beautiful mountain scenery,” the film showed how real-life film locations and opera can be inserted into and used as the foundation of a film without feeling forced or excessive in style. In this post, we’ll look at the film’s usage of the “glass mountain” fairytale and the film’s real-life opera connections.

Without giving too much away, the fairytale takes us from Norway to Germany and to places like Ancient Egypt!

What’s The Plot?

The plot may be just as important towards understanding the film as knowing the folklore behind it. Here’s my attempt at summarizing what is a relatively linear but all-together complex film.

A couple see a charming cottage but they know they cannot afford it. This vignette is quickly broken by the reality that WW2 has begun. Richard Wilder, a composer without luck nor prospects for success, is drafted into the RAF. However, he’s found unconscious in the Italian Dolomite mountains by Alida. After he’s revived, she shares with him the story of two doomed lovers and their demise on the glass mountain.

Upon WW2’s end, now married Richard has begun to write an opera on the subject entitled, “La Montagna di Cristallo (The Glass Mountain).” He finds out that Alida has left for the UK to receive an award and, because he can’t get in contact with her, realizes he loves her and not his wife. Richard returns to Italy and gets his opera accepted to be performed at La Fenice. Alita has become loved by another man and although Richard and him fight, nothing is resolved. He eventually leaves Alida, although not wanting to. Ann, Richard’s wife, asks a friend to fly her to the premiere of Richard’s opera but they crash when the fly over the real “glass mountain.”

The real opera tells the story of two fated lovers, Antonio and Maria, who both end up dead at the hands of the prophecy which the folk story entails. Essentially, the story the fictional opera tells is about a couple who break up with each other after promising to climb the mountain together. When Antonio is to be married to another woman, he hears Maria’s voice and climbs the mountain. However, he falls to his death.

After the premiere, Richard receives an ovation but his infidelity with Alida is discovered and he must choose. Richard chooses Anne and goes to find her on the mountain, much like Antonio had wanted. Seeing as she got injured, he realizes that life is worthless without his wife and dedicates his life to her from then on.

The Many Tales of “The Glass Mountain”

The story of the “glass mountain” is quite old and with some of the first ethnic tellings of the story stemming from the 15th to the 19th centuries. However, the most typical of the tellings come from the Polish fairytale, “Szklanna Góra,” translated into German as “Der Glasberg.” In this story, originally published by 19th century German poet Hermann Kletke, a lonely princess is trapped within the confines of a glass mountain on top of a mountain, with apple trees under the window. Time after time, knights would attempt to come and save her from her plight by picking an apple and bringing it to her. Yet, each time they would eventually perish at the hands of a protective eagle which would attack those who came near.

One day, as these stories so often go, a school-aged teen boy ventured to pick an apple and marry the princess. However, after battling the eagle and cutting off his feet, the boy fell into the tree and successfully picked an apple. Thus, he came to marry the Princess, and the blood of the eagle restored the taken lives of those who attempted to reach the apple. But why was the girl put into the castle in the first place you may ask? Here, one must go to another fairy tale, this time the fairytale entitled, “Old Rinkrank,” first collected by German philologists Jacob and Wilhem Grimms in the mid-19th century in the collection “Children’s and Household Tales.”

In this version, a stubborn and unhappy King has his daughter kept in a castle made of glass on a mountain in order to prevent and frustrate potential suitors from marrying her. To try and escape this reality, the Princess aids a potential suitor. But, she ultimately falls into a dark hole, only to be very nearly freed by Old Rinkrank who all but forces her to become his servant. The story eventually unfolds that she’s saved, marries her Prince, and Rinkrank gets put to death.

Yet, there are two more parts to the story of the “glass mountain.” One comes from Norway, while the other comes from the world of Ancient Egypt. The former pertains to the Nordic fairytale, “The Princess on the Glass Hill,” collected by Norway’s own version of the Grimms Brothers, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe. The tale was first published in their 1870s collection of fairy tales, “Norwegian Folktales” (Norske Folkeeventyr). It documents the trials of the suitors of a King for the hand of his beautiful daughter. Three brothers were given trials but ultimately the smaller of the three prevailed and was given half the kingdom and the Princess’ hand in marriage. While upbeat and overall congenial, the root of all these different versions is far more existential in nature.

Entitled, “Tale of the Doomed Prince,” this story comes from the 18th Dynasty (1550-1292) of Ancient Egypt. The story can be found part of the document known as the “Papyrus Harris 500.” Contained as well are some songs and further poetic verses and were part of the burial possessions of Pharaoh Intef VII (in Egyptian, Sekhemre-Heruhirmaat Intef). While the title gives a sense of dread, the story follows that of the three-trial format, with the Prince being tasked with three seemingly challenging tasks but ultimately succeeding in all of them.

In the process, he marries the daughter of the King. However, the second portion of the story sees the Prince get into contact with dangerous animals, with the fragment cutting off after that. Whether he rises to the occasion or ultimately dies is unknown. The emphasis in the story is placed on heroism, self-sacrifice, and bravery in the face of the unknown adventures that life normally holds for us.

The Real Operatic Connection

The film’s opera connection extends well past simply using opera as the central theme of the story.

Instead, the film has real-life connections to the operatic world through the place where the film was premiered to the actors and actresses who acted in the film itself. For background, opera singers acting and singing in many cases, within opera-related films is definitively not an oddity. Instead, it is actually quite frequent. In previous posts, I’ve talked about singers who’ve been in opera-related films.

For example, in Francesco Rosi’s “Carmen” the mezzo-soprano Faith Eshem sang in the role of Micaëla, while Julia Migenes-Johnson sang in the title role. Other notable examples include Gino Sinimberghi’s appearance in Robert Leonard’s “The World’s Most Beautiful Woman“ and Kitty Carlisle’s participation in Sam Wood’s “A Night at the Opera.” But what about this film you may ask? Well, two new names to Opera Meets Film are featured.

I’m talking about the world-renown 20th century Italian baritone Tito Gobbi. He is not a stranger to Operawire nor the stage, and Italian soprano Elena Rizzieri. Take a listen to her “Si, mi Chiamano Mimi.” In the film, they play themselves, but it is Gobbi’s singing of the film’s main theme song, “The Legend of the Glass Mountain,” written by Italian composer Nino Rota which cemented his fame as connected to the film.

The song had been recorded by numerous groups during the mid-20th century, one such recording being the 1951 recording by the group known as “The Three Suns” with pianist Larry Green. In terms of film participation, Gobbi had participated in other films as well. In 1937, Gobbi participated in the opera-based film “Condottieri,” directed by Italian director Giuseppe Becce. The film follows the life of Giovanni de’ Medici and doesn’t pertain to opera, per se. However, later in films like “Soho Conspiracy” (1950), shot by Cecil H. Williamson, demonstrated just how dedicated Gobbi was to the art of film.

Elena Rizzieri was also equally as influential in film, although participating in less than 10 films during her career. According to some, her beauty was the reason why earlier in her career she was being invited to perform in films much like the screen giants and operatic sopranos of the time, Silvana Pampanini. Her second film, “On Such a Night,” shot by Anthony Asquith in 1956, featured Rizzieri as Susanna, the maid to the Countess. The opera element in the film is noticeably taken from W. A. Mozart’s “Le Nozze di Figaro.” Although, the entire film is based around events which occur at the Glyndebourne opera house in Sydney, Australia. After this film, it’s unclear if she continued with film as there isn’t much information to go by. She continued singing in performances around the world until the early 1960s.

Two other elements that are worth mentioning is the usage of the Venice Opera orchestra in the filming and music of the film. Venice being the subject of an earlier Opera Meets Film. But more importantly, the usage of the La Fenice opera house in Venice as a location for the film. The site has been featured in many other films including “Death in Venice” (1971), “Senso” (1954), “The Anonymous Venetian” (1970), and opera-based film “Die Tote Stadt“ (2011) just to name a few.

Perhaps one of the more famous usages of the site is the 2004 video recording of Verdi’s “La Traviata” featuring Russian baritone Dmitry Hvorostovsky and Italian soprano Patrizia Ciofi.