Opera Meets Film: The Realism of Francesco Rosi’s ‘Carmen’

By John VandevertFilms based on opera often feel inadequate. They are frequently an attempt to introduce reality into art, and this concept is flawed. Directors fail to realize that what it should be is the other way around: bringing art into reality, making opera about human beings and their everyday trials. Luckily, some directors do know what they’re doing, and Italian director Francesco Rosi was one of them. In 1984, the year that Steve Jobs launched the first personal computer and the Challenger Space Shuttle embarked on its’ tenth mission, Rosi gave to the world his version of Georges Bizet’s beloved opera “Carmen.”

It is interesting that 1984 was also the year in which Philip Glass premiered his now revived opera “Akhnaten” and Luciano Berio staged, for the first time, his criminally underperformed opera “Un re in ascolto.” Within the cinematic world, the internationally-acclaimed hip-hop film Beat Street premiered at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, the same year as the premier of the equally popular breakdancing film Breakin’. This is all to say that 1984 was clearly a very important year on all sides of the cultural spectrum.

Rosi had recently finished the film “Three Brothers,” based on the eponymous novel by Andrei Platonov, winning several awards for his efforts. He now had the time, energy, and means to make another huge splash in the cinematic world. Only a little earlier, stage and film director Franco Zeffirelli had planned to make his own cinematic version of “Carmen,” but thankfully he had never realized the project: Zeffirelli’s vision for opera adaptations was not always clear, and it was he who had so ruined Samuel Barber’s opera “Antony and Cleopatra” at the MET in 1966. The path was clear for Rosi. With an all-star cast, including Placido Domingo as Don Jose, Rosi’s operatic film blurred the line between reality and art, casting the bohemian femme fatale Carmen as a fiercely independent woman who is hobbled by love. Winning a multitude of awards at the time, the film has begun to collect dust on the shelves of cinematic history: but that does not mean it has lost any of its original glamour. To understand the relationship between director Rosi and composer Bizet, let us look at two key factors which unify these creators.

Mutual Inspirations for “Carmen”

Before Bizet’s “Carmen,” other composers had tried their hand at the theme. Adolphe Adam—mentor to Léo Delibes, composer of “Lakme”—and his 1849 opera “Le toréador,” is just one example. It was a popular trope, one inspired by the nature of literary publishing in France at the time. The mid-19th century saw a boom in publicly available publications for readers of all backgrounds to peruse. In these monthly—or bi-monthly—journals, know as ‘revues,’ contained articles on nearly any topic: their primary purpose being to educate readers on the world beyond France. Founded in 1829, the still-running publication Revue des Deux Mondes was geared towards the cultural, political, and economic union between the United States of America and France, and celebrated scientific, artistic, and political triumphs. Reviews of opera were also published in these magazines. A notable example was Camille Bellaigue’s review of Jules Massenet’s twelfth opera “La Navarraise,” describing the opera as “like an element of eternity.” Another revue, Le Tour du Monde, was formed as a travel journal. At a time when global travel and the importation of foreign cultures was becoming not only feasible but desirable, the publication helped its’ readers discover the world. From the mid-19th century into the early 20th, the journal documented archeological and geographical discoveries of nearly every kind. Le Tour also played a part in the story of “Carmen.”

French artist Gustave Doré, whose son M. Ernest Doré would later become a minor composer, made over 350 engravings of provincial life in Spain accompanying ‘Voyages en Espagne,‘ an illustrated serial by art collector Charles Davillier published in Le Tour in 1873. This was during the interim period between the publication of Prosper Mérimée’s novel which famously inspired “Carmen,” and before Bizet’s premiere of the opera itself. There is reason to suspect that Bizet was as inspired by Doré’s illustrations as Mérimée’s short stories, for within the Francophile fine art realm, and thanks to the popularity of the revues, bohemian themes and Spanish exoticism were all the rage. Perhaps the most well-known examples come from the painter Édouard Manet. During the 1860s, he was captivated by the allure of Spain, and his paintings ‘Lola de Valence,’ (1862) and ‘Gypsy with a Cigarette’ (1862), both show an unmistakable similarity to Bizet’s 1875 heroine. Manet was himself inspired, in turn, by Bizet’s masterpiece, as seen in his 1880 painting ‘Emilie Ambre in the Role of Carmen.’ Further overtures of “Carmen” can be seen in ‘Bohémiens Going to a Fête’ (1840) by Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña, who was known for his woodland paintings and ability to depict rugged merriment. Fine art’s connection to Bizet is not only epochal, but tangible. Only ten days after “Carmen’s” premiere, on March 3rd 1875, engraver Pierre-Auguste Lamy created four engravings of crowd scenes based on the opera’s acts and set designs by Antoine Choudens. These illustrations have helped researchers piece together what the premiere must have looked like. We also know what some of the costumes would have looked like, too, thanks to drawings made by orientalist painter and illustrator Georges Clairin who, in 1875, drew the two leads.

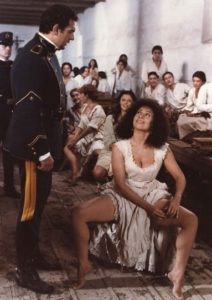

Rosi was evidently familiar with the artistic milieu that had surrounded the genesis of Bizet’s masterpiece. He sought to create Doré-like scenes, shooting the operatic film outdoors. He tried to capture as many natural effects as possible in an effort to harness the power of cinematic realism. Rosi was convinced that Bizet had been influenced by Doré and wanted to go even farther by tracing Doré and Davillier’s journey through Spain for himself. To capture the magic of what he saw as the ‘cultural truth,’ Rosi used the real locations from Doré’s sketches for his film, staging the opera in these historical, physical places. The film was shot in Andalusia, which is a region known for its flourishing cultural environment. During the late 18th and 19th century—the height of Romanticism—Andalusia was the epicenter of the burgeoning artistic style known as costumbrismo—equivalent to Italian verismo—a visual and literary style that favored unadorned depictions of real life as opposed to the flowery idealism of the previous century and the impending cosmopolitan industrialisation that would follow in the 20th century. A central pillar of costumbrismo was the honoring of local traditions and customs. It is not hard to see how Bizet’s “Carmen” was a part of this world, and why Rosi wanted to continue this legacy. To ensure true verisimilitude, Rosi hired genuine Romani, local villagers, and soldiers to populate the film’s many crowd scenes, obscuring the boundary between film and reality. Another critical aspect of his film was striking a balance between light and dark—’chiaroscuro’—allowing the innate levity of Bizet’s opera to sit adjacent to the heaviness of the central story. In discussing the choreography, Antonio Gades remarked that Rosi’s true gift was merging scripted movement with natural celebrations that one would find in the original cultural setting. “My choreography is discreet,” he remarked, “Almost unnoticeable. It is a popular fiesta more than a choreography.”

Rosi and Bizet’s Ideal Woman

Performing on the night of the premier, in March 1875, were some of France’s best singers. In the role of Carmen was the striking Célestine Galli-Marié—who was also the model for the illustration drawn by Georges Clairin. Galli-Marié was the daughter of opera singer Mécène Marié de l’Isle, who had been the original Tonio in Donizetti’s “La Fille du Régiment.” Her career began in her late teens, and by the mid-19th century she was singing at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. It is speculated, rather fascinatingly, that she not only predicted Bizet’s death, but that she personally asked him to create the role of Carmen. Whether true or not, Galli-Marié was widely known for her nimbleness onstage and impeccable singing, and after audiences heard her in Ambroise Thomas’s “Mignon,” there seemed little question who would play Carmen. Though negotiations of pay and logistics would go on for a while, and Galli-Marié’s tour dates considerably complicated matters, her participation in the role was allegedly cemented when, according to writer Henry Malherbe, Bizet and Galli-Marié entered into a relationship.

Over the course of 1874 Bizet and Galli-Marié exchanged letters and began to fall for one-another. By September the rehearsals had begun, and as they continued, and the premiere came and went—it was not well-received upon opening as it was considered a very controversial story for the time—Bizet would increasingly rely upon Galli-Marié. Because the opera was being critically challenged, Galli-Marié became the symbol of stalwart dedication to Bizet’s vision. As Mina Kirstein Curtiss writes, Célestine Galli-Marié ‘became the embodiment of [Bizet’s] creation by her own gifts, her faith in his talent, her fierce loyalty to his conception of the interpretation of her role.’ Upon Bizet’s death, praise began to roll in for a composer who had been widely scorned for his ostensible ‘distastefulness’ in regards to “Carmen.” Galli-Marié continued to sing Carmen, praise heaped high as she went. Though, upon the opera’s resurgence in the 1880s at the Opéra-Comique, its lowly nature was a vast departure from its original quality, it is thanks to Galli-Marié that we are still talking about “Carmen” today. During her time in the role she was considered scandalous and extreme, yet her novel dramaturgy has inspired many subsequent iterations of Bizet’s tragic heroine.

For Rosi, the process of finding his Carmen was very much the same. Not just anyone could portray her, but someone who could navigate between ferocious sensuality, playfulness, sincerity, calmness, scornfulness, and genuine humility. Her sentiment had to differ depending on who she was with; her demeanor had to change considerably when occupied with dancing. Carmen must be able to pierce the heart of her admirers without giving an inch of space to them, yet not be so cold as to push him away. Rosi’s Carmen was to be modeled after the traditions and way of life of the Romani people. Having come from India through the Middle East in the 3rd century, making their way into Europe by the 14th century, and establishing themselves as a fully-fledged, independent culture by the 15th century, Romani people—also known as Roma, Sinti, and Calé—have suffered ongoing persecution and discrimination throughout their history. Despite their endless battle against xenophobia, it was “gitano” culture—an exonym for the Roma people of Spain which, unlike its’ English-language equivalent, is not widely considered a pejorative—that would give rise to the phenomenon of Flamenco dance; which would inspire the painter Manet; and whom Bizet would valorize with his opera.

To fill this massive and demanding role, the American musical theater performer and operatic soprano Julia Migenes-Johnson was chosen. To prepare for the role, Migenes-Johnson had to train to lower her naturally high voice to fit the sultry depths needed for Carmen. She also had to learn how to dance Flamenco, taking classes with Gades’ ballet company. Once the film was released, reviewers were immediately struck by Migenes-Johnson’s alluring embodiment of Bizet’s femme fatale. Pauline Kael wrote, “Julia Migenes-Johnson’s freckled street urchin Carmen revitalizes the story.” Appearing alongside Migenes-Johnson were several big names of opera, including Plácido Domingo as Don Jose, Ruggero Raimondi as Escamillo, and Westminster Choir College faculty member Faith Esham in the role of Micaëla.

It is clear from all reviews that Migenes-Johnson’s performance tapped into the heart of Carmen, that she embodied the dangerous and seductive sense of manipulation which defines her, her femininity becoming a tool to command those around her, to bend their wills to her desire. When Carmen dies at the end, Migenes-Johnson’s beauty makes the moment all the worse: her tortuous allure and dogged knowledge of self makes her someone whose life would never be taken for granted, and whose death is devastating.