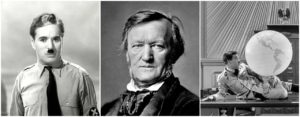

Opera Meets Film: Charlie Chaplin’s Contrasting Use of ‘Lohengrin’s Prelude in ‘The Great Dictator’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator.”

To hear the music of Richard Wagner in “The Great Dictator” immediately brings forth a number of associations that are a part of the film’s text.

The Charlie Chaplin film is an iconic comedy in which the director portrays a farcical version of Adolf Hitler known as Adenoid Hynkel. Hitler, of course, was a massive fan of Wagner’s music and the famed composer’s music became associated with Nazi Germany for some time thereafter.

So there is no doubt that in bringing forth “Lohengrin,” Chaplin, whose film is pretty overt about its meaning, is blasting us right in the face with this real-life association as an identifier of Nazi Germany at the time the film was created (1940).

This is no throwaway fact. Chaplin’s choice to make this film was not embraced in the U.S. Hollywood, hoping to keep itself afoot in the German film market, was not particularly open about taking sides in the escalating conflict in Europe. Meanwhile, United Artists, which Chaplin had co-founded, was afraid that the controversial picture might not even be allowed in the English market.

As Chaplin moved into production, there were suggestions that he might run into censorship issues from the Hays Office. The pressure increasingly mounted from there on out with calls for him to not make the film.

Chaplin himself had a personal bone to pick with the Nazis. He had been run out of Berlin in 1931 by pro-Nazi propaganda that claimed he was an “American film-jew” and “a disgusting Jewish acrobat.” His films were banned as well.

So Chaplin was all in on ridiculing Hitler and the Nazis and he was going to use every weapon he could. That included ridiculing what Hitler loved most, Wagner, before using it against him.

That brings us to the iconic Globe scene where Hynkel, after hearing from his trusted man Garbitch (sounds like “garbage”) about how he can rule the world and be seen as a god, asks for some alone time. He walks over toward a globe in the middle of the room, removes it from its holder and reveals it to be a beach ball. He starts to bounce it around gracefully in a scene that brings the viewer back into Chaplin’s era of silent filmmaking (“The Great Dictator” was his first complete sound film).

To the strains of the opening overture of “Lohengrin,” the scene takes on some serious cognitive dissonance. The gentle, ethereal music that opens Wagner’s famed opera is sublime. It is undeniably some of the most breathtakingly beautiful music EVER written.

And while Hynkel’s little playtime session features Chaplin’s graceful movement, it is a childish display. It undercuts the music in a subtle way.

But again, the choice is overt because Chaplin wants to link the film’s associations to the real-life relationship between Hitler and Wagner. And in doing so, he almost makes the audience wonder – how could such a ridiculous monster like Hitler have any kind of appreciation for this glorious music (Wagner’s own antisemitism might complicate the reading, but then again, they might bring back that very question with regards to the composer himself – how could such a bully of a man have created such sublime art?).

As the prelude moves toward a climax, the balloon/beach ball pops in Hynkel’s face; the music abruptly concludes.

Finding the Sublime in the Ending

Contrast this with the ending of the film when the “Lohengrin” prelude returns right after the barber’s final speech, delivered with Chaplin looking right into the camera (many saw it at the time as a call for the U.S. to take a stand against fascism).

“Let us fight to free the world – to do away with national barriers – to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. Let us fight for a world of reason, a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness. Soldiers! in the name of democracy, let us all unite,” Chaplin says in the speech’s final words.

The barber / Chaplin then shifts his thoughts to Hannah and delivers the remainder of his speech directly to her, telling her, from afar, of “coming into a new world, a kindlier world, where men will rise above their hate… The soul of man has been given wings and a last he is beginning to fly.” He speaks of a “glorious future that belongs to you. To me,” all underscored by Wagner’s prelude.

This declaration of hope embraces the music in a way that opposes its ridicule in the earlier scene. In using the piece of music at this moment, Chaplin immediately associates the two scenes within the film, driving home his social and political message in a rather earnest but effective means. The earlier scene of a childish man trying to conquer and hold the world in his hands pales in comparison to that of a valiant man standing up to fascism.

Opera lovers who know the story of “Lohengrin” also recall Elsa von Brabant’s ordeal in the opening Act. She’s being unjustly blamed for the death of her brother and is being threatened to death, a parallel to the plight of the Jewish people under Nazi rule who were scapegoated for the country’s own misfortunes. But as in the opera, where the titular character arrives amidst this very music to save her from the worst fate, Chaplin’s speech provides a saving grace for Hannah and the other Jews suffering.

The music’s original meaning and context thus become part of the subtext of this film’s scene, again providing an internal opposition to the buffoonery of the balloon scene and its contradiction of the glorious music. It is at the end, where Chaplin not only allows us but asks us to truly appreciate the music’s ethereal beauty. The beauty that the reawakened “soul of man” is capable of.

Categories

Opera Meets Film