Opera Australia 2022 Review: Otello

Marco Vratogna & Yonghoon Lee Shine in Verdi’s Tragic Masterpiece

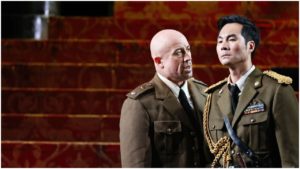

By Gordon Williams(Photo credit: Prudence Upton)

Whose version of “Othello” is better – Shakespeare’s or Verdi’s? You could have a good argument with someone over this.

In Verdi’s opera, Iago is more overtly a villain (he says so in Act two’s “Credo in Dio crudel”) and there are potentially more shades to Otello, whose long speeches in Shakespeare’s “Othello” can too easily become generalized railings.

One of the opera’s biggest plusses is that Verdi jettisoned Shakespeare’s Act one so that his “Otello” could open with the storm that begins Shakespeare’s Act two. Music does storms beautifully and Harry Kupfer’s 2003 production for Opera Australia revived here at the Sydney Opera House by Luke Joslin grabbed our attention immediately.

This was our first chance to evaluate the Kupfer/Joslin staging. The chorus rushed in from “outside” and scattered down designer Han Schavernoch’s huge staircase. Upstage shutters banged in a way that might remind Sydneysiders of the sudden onset of a Southerly Buster.

The opening needed to make us sit up and it was hair-raising from Italian conductor Andrea Battistoni’s downbeat to begin the performance to the tutti “Dio, fulgor della bufera! (God, the splendor of the tempest)” – the Opera Australia Chorus coming at us from just about every available space on the stage up to the proscenium. Battistoni’s musical conception of the opera was well-paced yet able to convey hidden depths; for example, inner turmoil at the beginning of Act three, or the rich movement of the inner parts in Act four’s “Willow Song.”

Once again, the Opera Australia Chorus was beautifully prepared by Paul Fitzsimon. Another of those wonderful tuttis extracted the maximum of poignancy at the end of Act three when the chorus sympathized (“we’ll weep with you”) with Desdemona, falsely accused of betrayal by her jealous husband, Otello.

The immense wide staircase creaked on occasion (Opera Australia’s publicity overtly states that it is “precarious”), but it was an excellent tool for graphically illustrating the upstage-downstage dynamics that define the power relationships between the characters. One example was the quartet, “Dammi la dolce e lieta parola,” Desdemona’s plea for pardon ignorant of how she’s caused offense. Up on those stairs, Iago (Italian baritone Marco Vratogna) could maintain the dominant position. And at the very end of the opera, Otello (South Korean tenor Yonghoon Lee), remorseful at having killed Desdemona (soprano Karah Son) and dying from a self-inflicted wound, couldn’t quite make it back up the stairs to kiss the wife he has so unjustly punished.

Two Handers

“Otello” is an opera of great two-handers. Iago and Roderigo (Hubert Francis) who will soon start plotting together penetrated the great mass of opening chorus, while the scene where Iago gradually gets Cassio (Virgilio Marino) drunk as a way of destroying his new authority in the eyes of Otello was an effective comedy routine that became deadly serious.

Iago effectively flailed Otello in their great Act two vengeful finale, “Sì, pel ciel marmoreo guiro” with the heavy emphasis of his aspirated consonants.

In Verdi’s conception Desdemona is kept offstage at the beginning of the opera so that she can make a fresh impression at the end of Act one for the love duet with Otello who is not yet poisoned against her by the dastardly Iago. Seoul-born soprano Karah Son portrayed the unjustly accused Desdemona with much poignancy.

Her delivery of Desdemona’s famous ‘Willow Song’ and “Ave Maria” garnered deserved applause in this account of another’s love-gone-wrong. By the way Son’s green costume (Yan Tax was the costume designer) couldn’t help but remind us of Iago’s ironic warning against the green-eyed monster, jealousy, which is exactly what he’s planted in Otello’s mind. Visuals underlined for us that Desdemona has walked innocently into Iago’s trap.

And in another of those two-handers, the closeness of Desdemona’s relationship with her maid, Emilia (mezzo-soprano Sian Sharp), who is gradually waking up to the set-up against Desdemona, was detailed down to almost seamless transfer of timbre between them in the last Act when Desdemona has a presentiment that she will be murdered.

The love duet with Desdemona is one of Otello’s opportunities to show a softer side to his soon-to-be corrupted character, and the opening paragraph of Yonghoon Lee’s ‘Già nella notte densa…” was delivered with such simplicity as to make it one of the most beautiful moments in the performance. The whole of this duet made clear sense of the lyrics, especially in Lee and Son’s remembrance of Otello’s past deeds and how his recounting of them had won her to him.

Two Opposing Forces

What of Otello himself? In Shakespeare he demonstrates his magnificence in Act one fending off a charge of witchcraft. Verdi and his librettist Boito’s omission of Shakespeare’s Act one therefore throws enormous weight on Otello’s entry, and since the opera’s premiere in 1887, comparisons have been made between various tenors’ delivery of Otello’s opening lines as he arrives announcing the destruction of the Turkish fleet: “Esultate! L’orgoglio musulmano / sepolto è in mar…” With almost an upward glissando to the first syllable and long notes, Yonghoon Lee drew out Otello’s exaltation. There was an earnestness to Lee’s entry, and “earnest” could perhaps be the best adjective to describe his overall characterization of this great general. Interestingly also, Lee delivered Otello’s later number “Ora e per sempre addio” quite quickly (it is a cabaletta, after all) while managing to convey Otello’s regret at farewelling his great achievements and past glories.

Lee’s exuberant gestures – though they admitted the audience into the contours of Otello’s music – conveyed an eagerness to communicate that could be seen as at odds with a character who might at least have started out as more monumental. That, of course, depends on your reading of the part, but surely part of the point of Otello/Othello is the depth of Otello’s fall from impressive and, even, legendary height. Some of the more effective moments were when Yonghoon Lee and Karah Son stood still in each other’s arms, as in the love duet.

Verdi originally thought of calling his opera “Iago” in order to distinguish it from Shakespeare’s original. In fact, you could say that Iago is the protagonist in the original sense of “one who takes the lead.” Italian baritone Marco Vratogna presented an Iago whose range of vocal devices could serve as an analogue for “trying every trick in the book” as he sought to corrupt his hated rival Otello’s feelings for his wife. In Iago’s great Act two monologue “Credo in Dio crudel,” Vratogna drew out in sustained notes the proclamation that he believed in a cruel God; his voice itself seemed to smile through the admission (“Son io”) that he was the villain. At the point where the nihilist proclaims that death is meaningless, Vratogna virtually spoke the key word: “nulla.”

In Act two his “Soffri e ruggi!” formed a prominence in Vratogna’s performance that spoke to an intelligent architecture in his interpretation. In fact, could his drawing out of the selfish “Credo in Dio crudel” have been designed to complement the altruistic Otello’s “Esultate?” You would have to ask Battistoni and the artists, I guess.

All in all, a production that convinced me that I currently prefer Verdi’s version of this great tragedy. It paints the story in swift and profound strokes and derives its energy more clearly from Iago. Certainly, this performance did.