Metropolitan Opera 2022-23 Review: Peter Grimes

Nicole Car & Allan Clayton Deliver Incredible Turns in Ever-Timely Britten Masterwork

By David Salazar(Credit: Richard Termine / Met Opera)

(This review is for the performance on Oct. 26, 2022)

The last time the Met Opera presented “Peter Grimes” was in 2008. The world has certainly changed quite a bit in that time and somehow, that timeless work’s themes seem all the more relevant than ever before.

The opera opens on the trial of the titular character for the death of his apprentice. He’s acquitted of any wrongdoing, but it isn’t long before the townspeople ostracize him. And then the cycle repeats. Was Grimes always a monster? Or did his (possibly) unjust cancelation (to stick to the modern milieu) become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The opera’s ambiguity is such that one might even go so far as to see Grimes as a victim of circumstance who never wronged anyone.

And all of these colliding possibilities made this particular performance (on Oct. 26) particularly striking and fresh.

Dark & Unyielding

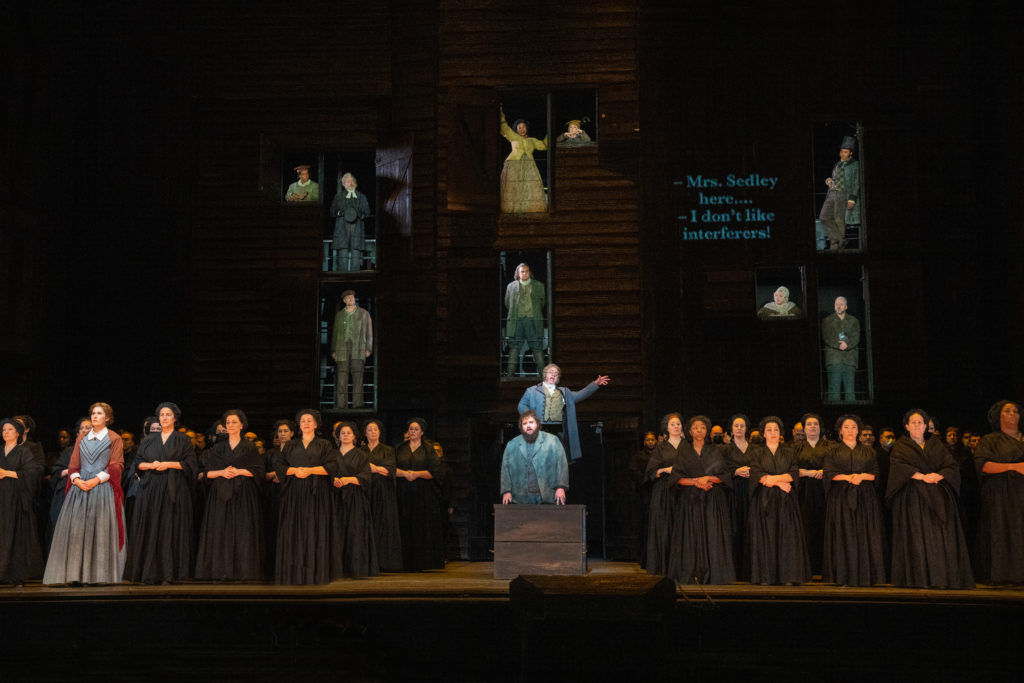

The production by John Doyle certainly adds to this tension. With its monochromatic look and constantly shifting panels, one gets the sense of uncertainty, coupled with instability, and a general lack of warmth (which underscores the opera’s general lack of empathy from almost all the characters save for Ellen, who incidentally opens the opera wearing a red shawl over her gray dress that pops against the sea of black attire elsewhere). Every time the titular (anti)hero shows up, the walls close in on him, the light darkening each time; by the time Grimes appears in the opera’s final scene, the walls merge into a narrow corridor through which the protagonist appears, the lights dimmed to a cold blue.

During several of the famed interludes, the panels come together to create a screen through which we see black and white projections of the sea. Back in 2008 it MIGHT have seemed like a good idea, but it wasn’t and time has only emphasized that point; they are not as disappointing as the projections on the famed $15 million Ring Cycle Machine because they aren’t expected to carry the opera like that production does, but placed alongside such evocative passages as the sea interludes, the imagery simply pales by comparison. Instead of letting the music guide our imaginations, we are subjected to monotonous and repetitive images that lack development or momentum. They end up undercutting the music. This is definitely a place where less would be more and the production would have done well to ditch them altogether.

That aside, the production’s other major fault lies with the acoustics. When the panels shorten the stage, they allow for a greater deal of clarity. But when they push all the way back for the big choral scenes, the effects can undesirable. For one, the staging clearly aims to put all the soloists as close to the front of the stage as possible, because when they aren’t and the stage is at its most open, the sound lacks clarity (mind you, I was sitting in the center of Orchestra section). But even then, ensemble sections can get all sorts of messy (and they did with “Old Joe has gone fishing” the saddest example) with the sound scattering.

The Borough Folk

Which brings us to the chorus, representing the people of The Borough, which is essential to the opera’s construction.The Met Opera Chorus is one of the finest ensembles of its kind and most nights (almost every single one) they are at the top of their game. The ensemble was undeniably in top form on this evening, able to conjure up unforgettable moments throughout the many climactic scenes; the third Act’s “Who holds himself apart” was a perfect example of this. There was precision throughout the march-like passage, all of the lines combining and crossing perfectly throughout, building and building to the climactic cries of “Peter Grimes;” it has been a long time since I have felt such electricity, tension, and anticipation during lengthy fermata rests, but it was all there. Every. Single. One. The final fff “Grimes” was terrifying in not only its emotional content, but in the magnitude of the chorus’ power. Even remembering that moment as I write about it gives me goosebumps. Another major moment came early on as the chorus uttered the line “because the Borough is afraid you who help will share the blame,” the mounting crescendo creating a veritable tension when paired with Nicole Car’s solo replies. Ditto for the ensuing passage as the chorus trembles over the incoming storm, the voices rising and falling like ocean waves with each dynamic and rhythmic shift.

But then there were moments like “Old Joe has gone fishing,” which admittedly, with its 7/4 time signature, is a hell of a challenging round; as more and more pieces were added to the piece, things sounded increasingly mushy. That might have been an issue with the ensemble on this evening, but as stated earlier, I don’t think the production helped much either.

“Peter Grimes” is a major ensemble opera which, aside from featuring the chorus, also includes several supporting roles that are essential to the inner workings of the opera. In her Met debut as Auntie, Margaret Gawrysiak made a fine impression with a round mezzo and a playful demeanor throughout. But there was no doubt that her finest moment came during the glorious Act two quartet “From the Gutter.” Together with Brandie Sutton, Maureen McKay, and Nicole Car (more on her later), Gawrysiak’s earthy tone provided a tremendous counterbalance to that of her colleagues, grounding this ethereal piece of music.

Sutton and McKay, as Auntie’s mischievous nieces also made their presences felt in this passage, the two providing a glorious high A / D flat harmony at the apex of the passage. Both Sutton and McKay are inseparable throughout the opera, often combining lines, playing off one another, or harmonizing; the two were a dynamic duo that was a joy to watch throughout the evening.

As Ned Keene, baritone Justin Austin was a standout. His character appears sympathetic to Grimes early on, but as the work develops, he shifts in his position. Austin reflected this shift through his more delicate and lighter vocal texture early on in the opera, delivering the opening “Old Joe’s has gone fishing” with suavity. But by the end of the opera, his interjections had a roughness to them as he joined in on the lust of vengeance against Grimes.

Contrast this with tenor Tony Stevenson, who took on the character of Rev. Horace Adams. Several of Grimes’ characters take on religious complexion and he himself claimed to be a dedicated Christian, but there’s no doubt that the Reverend, constantly quoting the Bible is not necessarily the most righteous of characters. In fact, he’s an irritant, something that stings all the more in the modern milieu. Stevenson did his utmost to bring this out, his tenor pointed throughout the evening, always rising over the general ensemble texture, something you’d expect from an antagonizing pastor.

The other major ensemble players, including Harold Wilson as Hobson, Chad Shelton as Bob Boles, and Leo Rempe-Hiam as John, were solid in their roles.

As Balstrode, Adam Plachetka added the much-needed contrast. His imposing “Look the storm cone,” gives off the idea this would be yet another unyielding character, and this was borne out in his confrontational approach throughout “And do you prefer the storm to Auntie’s parlour,” his pointed and accented vocal line almost admonishing Grimes. But then, his “Then the crowner sits to hint” took on a softer complexion, a warmer one even, that expressed concern for Grimes. In a later scene alongside Car’s Ellen, he was similarly supportive, his body language always open to her, his voice gentle, tranquil. Even in the opera’s final moments, when Ellen and him enter to find Grimes unraveling, everyone’s belief in his seemingly at an end, he looked on, a concerned expression at the man who he once seemingly considered a friend. You never got a sense the entire evening that Plachetka’s Balstrode had an ounce of doubt toward Grimes.

From Left: The Met presents Benjamin Britten’s PETER GRIMES

John Doyle, Production/Director; Nicholas Carter, Conductor

Met Orchestra and Chorus

Dress Rehearsals photographed: Tuesday, October 11, 2022; 10:30 AM at The Metropolitan Opera; New York, NY. Photograph: © 2021 Richard Termine

PHOTO CREDIT – RICHARD TERMINE

Two Geniuses

Soprano Nicole Car might have been the vocal standout of the night, delivering a complex portrayal of Ellen Orford. From the start of the opera, she’s there for Grimes; you immediately sense that she loves him and will stop at nothing to help him. To this effect, she delivered the dotted quarter + eighth note repeated rhythm of “The carter goes from pub to pub” with precision and firm sound, emphasizing Ellen’s unyielding resolve and fearlessness. After the chorus fired back its fears of her “sharing the blame,” she answered with an impassioned and similarly potent “Whatever you say, Let her among you without fault cast the first stone;” the passage constantly descends from high to low range, Car’s voice finding fullness and evenness throughout the passage. She was the embodiment of strength and consistency in this moment.

But things start to shift in Act two when she comes across the bruise on the boy’s neck; the moment Car found the bruise, you could immediately see the heartbreak in her eyes; you knew that her Ellen was already wondering the worst. And as Grimes rebuffed her aggressively, you saw her gradually lose hope, her undying devotion dying in those moments. That leads to the glorious Act three aria “Embroidery in Childhood,” which Car delivered almost as a lament, her delicate vocal line almost weeping for what she knew to be the dead child. The G on “Now my broidery affords the clue” is written ppp “senza espressione;” Car didn’t quite follow that diminuendo, but instead opted for the opposite; in this case, that choice fit well with her character’s sense of loss. As she descended the line, she diminuendoed to the thinnest thread of sound. For the remainder of the aria, her singing remained at its softest, drawing you into her pain, a double loss of the young boy John, but also any hope that she had for Grimes. The climactic high A and then B flat (against also written ppp “senza espressione”) were delivered as cries of longing. Once again, she diminuendoed the remainder of the aria, fading into nothingness on “whose meaning we avoid.”

In the title role, I don’t think you could do better than Allan Clayton, a surefire singing actor. He dominated in the title role of “Hamlet” at the end of last season and was just as spell-binding as Grimes. I didn’t mention it earlier, but the production’s monochromatic color palette (save for Ellen’s shawl) misses an opportunity to truly other Grimes visually; his grey attire might be somewhat different from everyone else’s but it doesn’t really feel as such in the larger context. He looks and feels much the same as everyone else. That puts the onus on the tenor interpreting the role to bridge that gap and really make the character feel like an outsider. And this is why Clayton is such a potent stage presence. From the get-go, his Grimes was a tortured soul, his “I swear by Almighty God” weighty and mournful; you could sense the weight of the guilt he was carrying. His body language throughout, hunched over and weary, only added to this sense of a man completely out of sorts with his life. Furthermore, his treatment of the child, brutal in the early scenes added to the complexity; on one hand you felt empathy for his loneliness and at others, you could relate to the Borough folk’s fear of him. By the end of the opera, crawling to the front of the stage and eventually collapsing, you truly feel that this man is so wracked with guilt and shame that he can’t bear it any longer.

His vocal interpretation of the role only added to his mesmerizing physical embodiment.

“Picture what that day was like” was full of anguish, every whole note high note almost an increasing cry until he ended the passage with a bitter and hardened delivery of “with a childish death.” He delivered the frantic “They listen to money” (which starts in the lower range”) with a whispery tone that added a sense of desperation. That emotion grew and boiled over as the passage developed with the high As on the repeated “I’ll marry Ellen” emphatic, adding to this sense of a man on the verge of a breakdown. The passage turns into a full-on duet with Balstrode, the two voices at odds; as Plachetka’s Balstrode looked on with concern, Clayton rushed about the stage, adding to the sense of frenzy. He capped the passage with the interpolated high A on “shall stay.” The ensuing “What harbour shelters peace” features a rich legato line from Clayton, expressing his character’s sense of longing, each phrase building all the way up to the high A on “Her breast is harbour too” and providing a magical vocal transition into the Interlude II.

When confronted by Ellen over the bruises on the child, he responded with a brutal, accented lines, his singing frayed and violent; his lunging at the child, grabbing him, and leading him away only added to the tension of the scene.

But then there was a tremendous vulnerability in the hut scene at the end of Act two. The opening of the hut scene starts with a cadenza that rises to a high B flat, followed by coloratura. Clayton delivered this passage as an impassioned cry. It’s an order in the score, and as written perhaps even a violent one, but Clayton’s singing was full of pain and ensuing passages didn’t come off as violent so much as desperate. There was a sweetness to his voice that softened the hard edges of the passage. The desperation returned as he implored the boy to join him at see, recounting his vows to Balstrode in Act one and climaxing in an impassioned cry on “We’re going to sea.” “In dreams I’ve built myself” was sung with a docile legato, his voice almost caressing each line of the memory. This was the most elegant and gentle singing of the entire evening, his voice rising to the high notes with glorious pianissimi. But as he neared the end of the passage, his voice took on its more violent force, crescendoing throughout “Calling there is no stone…” From here, the rougher texture of his voice slowly returned as Grimes grows more frantic about the oncoming crowd.

The final scene, which is essentially an extended recitative, saw Clayton use his entire vocal arsenal. His voice swayed from full-voiced to speaking sound, shifted from forte to piano, from pronounced vibrato to straight tone – there were several pronounced and extended portamenti – creating the effect of Grimes on the edge. The curt phrases, delivered with rhythmic precision (but without the feeling of it) only added to the effect of this “mad scene.” The final cadenza was delivered in one extended breath that felt like a long portamento up and down the vocal register, creating a disorienting and chilling effect. Topping it off was the final enunciation of “Peter Grimes,” delivered with cold, disembodied sound.

Mastery in the Pit

In the pit was Nicholas Carter, delivering a balanced and solid reading of, arguably, Britten’s greatest score. Save for the aforementioned sloppiness of the Act two round and some of the ensemble work at the start of Act three, he maintained a solid balance between the pit and the stage and was always connected with his soloists, especially Clayton.

One of the major features of this score are the six glorious interludes, all with contrasting characters and orchestral challenges. Carter managed each one exceedingly well with two providing the major standouts. Interlude II was one of his finest moments on the evening, the tempestuous passage full of forward drive, each orchestral line clear and balanced. The brass fanfare early on in the piece, a challenging passage that can be a victim of sloppiness, was crystal clear in its delivery; the transition into the shimmering string line (answered by an agitated woodwind figure) was breathtaking and smooth.

The same goes for the fourth Interlude, one of the great Passaglias in classical music. There were seamless transitions between variations, each one building with momentum and pace, the pizzicato bass theme ever present, unyielding in its precise articulation, and foreboding.

“Peter Grimes” is one of the great operas of the 20th century and it is rather shocking that it only has 75 performances at the Met to date. After seeing this cast take on the opera, there’s no doubt in my mind that it deserves a lot more and hopefully the Met won’t make it’s audiences wait another 14 years to hear all that this genuine masterwork has to offer. Last month, the Met Opera kicked off its 2022-23 season in top form and this “Peter Grimes” has kept that streak going.