Metropolitan Opera 2021-22 Review: Le Nozze di Figaro

Christian Van Horn, Ying Fang, Federica Lombardi, Gerald Finley Create Wholeness From Divergent Stylistic Approaches

By David Salazar(Credit: Ken Howard)

In the opera world, it’s a common cliché to think that Mozart, because of the simplicity of his music, is “easy to perform.” That’s often why we see opera conservatories and universities often take on his masterpieces for performances. But in my view, nothing is more challenging than Mozart.

Not only is the music itself complex in how Mozart articulates character, but the dramas themselves are arguably more involved than anything on offer anywhere else. That’s why “Le Nozze di Figaro” is arguably the greatest work ever committed to the opera stage. A tragedy and political drama portrayed as a comedy. Especially in today’s world, “Le nozze di Figaro” feels arguably more relevant than ever and the best productions of this work manage to balance these two lines – buoyancy of the comedy without forgetting about the class warfare, infidelity, and sexual abuse taking place.

That’s why I’ve always taken to Richard Eyre’s brilliant Met Opera production, it’s gilded cage set that overwhelms its characters with its size, while also symbolically trapping them in the social structures around them. The rotating set that goes in circles, literally accentuating the never-ending cycle of abuse (next to “Il Trovatore,” the only two rotating sets on the Met stage that actually make sense). The way Cherubino, who starts off very much as an individual in his pale, beige suit (which suggests his innocence), eventually finds himself dressed like and mirroring the Count (in a black tux) -emphasizing that the next generation of privileged men will be no different from the current one. Little details all over the place that highlight the different dramatic elements at play in this masterwork. And Eyre does this while allowing singers sufficient freedom to play up the comedic elements, which they always do.

And that’s probably the big takeaway for me. Every time I come back to this production of Mozart’s masterpiece, I find myself fully immersed. I don’t miss a beat. And after last night’s April 6, 2022 performance (the company’s 516th performance of the Mozart masterpiece in its history), I found myself toggling through past experiences of this very Met production and asking myself why this always seemed to happen? And the answer was right there on stage – the singers, no matter who they are, always seem to be having a blast with it. And this performance was far from the exception.

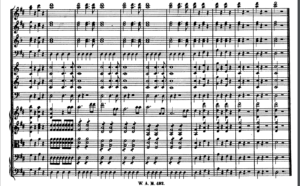

It all started in the pit where James Gaffigan led a sturdy performance. From the opening notes to the final ones, the opera sustained a solid pacing with seamless transitions during the longer finales; particularly impressive was the Act two finale with its ever-evolving structure and complexity, each shift in scene flowing naturally from what came before. There was no sense of stop-and-go to the music and the result was that despite running close to three hours in length, it flew by. There was restraint in the playing with orchestra chords never over-emphasized (this was particularly noticeable during the overture with the coda section where conductors have a tendency to overdo the final notes).

Gaffigan was finely attuned to the singers onstage throughout, flowing with them and always finding the appropriate orchestral balance to suit them. In Figaro’s Act four aria “Aprite un po’quegli occhi” there’s a section where Figaro alternates between a phrase sung on A, B, and C at the top of the stave and another full of low Bs. A lot of conductors overlook that the bass-baritone might need some help to project the lower notes and the result is that we don’t hear them with any discernible clarity. In the case of Wednesday’s performance, not only did the Met have a bass-baritone able to project down there, but Gaffigan’s ability to contain the orchestra during that section furthered the singer’s cause. “Sì, Vendetta” might not be the most popular aria in the piece, but it is a complex one, full of ebbs and flows, all while the second violins are flying around the instrument. Then you have to factor in the bass who has barely gotten a chance to sing anything up to this point and immediately has to pour himself into the aria. It can become a mess balance-wise both in the pit and onstage (I’ve heard it); Gaffigan managed that one particularly well, showing tremendous support for Mario Muraro who took some time to warm up but came away with a solid rendition of the section. The end result was that every singer on that stage came through clearly and every line of dialogue in the libretto was crisp and comprehensible. And in terms of overall approach, there was a restrained elegance that allowed for the music and drama to find a comfortable balance without the need to resort to vocal mannerisms that strayed from the style.

That isn’t to say that everything was pitch-perfect throughout. There were a few ensembles where the singers didn’t quite feel together (the septet that ends Act two felt a bit disjointed) and there was a duet where two artists seemed to want a faster tempo than Gaffigan was willing to give. But unlike other performance, where you can feel the tension and it’s impossible not to wonder if this might implode at any moment, you always felt secure with Gaffigan because every time there was even the subtlest of miscues, he adjusted quickly and decisively. And from there on, the music would proceed fluidly as if nothing happened.

Opposites Attract

Taking on the title role was Christian Van Horn. Using his imposing stature and robust bass-baritone, Van Horn created a much more grounded portrayal of Figaro. Whereas other interpretations in this production have emphasized the characters’ buffoonery (Figaro’s entire scheme in Act one is “not a good plan” and rightfully fails), Van Horn restrained that aspect, make Figaro more of a noble hero. One particularly section in this production that stood out was the moment of confrontation with the Count in Act three. Figaro’s plan has been exposed and the Count confronts him over it. In other performances of this production, most Figaro interpreters get to the point of responding to the Count by shouting right back on “Perché no? Io non impugno mai quel che non so.” Van Horn stood his ground on the line and then, using his massive frame, turned toward the Count and stood over him, eye to eye – it made the moment far more intense and emphasized Figaro’s strength.

This more grounded approach allowed some of his more soulful moments, like the Act four aria “Aprite un po’quegli occhi” to come off as introspective soul-searching rather than prickly and cynical. In this section, Van Horn, while emphatic and biting on the consonants throughout, managed some strong legato singing throughout. On the aforementioned section that alternated from higher lines to the low Bs, Van Horn not only projected the low piano notes prominently, but each alternating phrase was given a different feel and emotion, each building on the previous one like one emotional crescendo; it reflected Figaro’s bitterness, alternating with a sense of increased desperation. It was a masterful moment of dramatic insight through top-flight musicianship.

“Tutto è tranquilo e placido,” a moment at the end of the opera during which Figaro believes he has been cheated on, was given added gravitas thanks to Van Horn’s gentle legato line. And a similar suaveness materialized in the final moments with Susanna, the voice growing more potent as the flirtation with Susanna correspondingly increased.

That isn’t to say that Van Horn didn’t engage with the more comic aspects of the character. For one, everyone slaps him throughout the opera and the fact that those who do (mainly Susanna and the Count) were much shorter than Van Horn, added to the comedy of the performance. This cognitive dissonance made those slaps a lot more present than in any other previous performance, making them land with greater humor.

But Van Horn was agile and athletic, diving into the fun of his first aria “Si vuol ballare” with some subtle moves or overemphasizing the jump at the end of Act two when he declares that it was he who fell from the window. He proved a suave dancer during the wedding, twirling Ying Fang around. At the end of Act two, he literally picked Fang up and carried her away from the chaos of the scene.

He was particularly effective in expressing emotional transitions as well, none more engaging than the revelation of his parents (a moment that everyone involved contributed to brilliantly, I might add). You could see the truth dawn on him slowly – the disbelief, the stupefaction, and then, the most subtle of acceptances and joy. When a few moments later, Fang played up and expanded on her moment of the same realization, the scene only grew in its raucous comedy.

Vocally this was everything you would want from a Figaro interpreter. Robust and potent with crystal-clear diction (I am going to say this a lot), a voice that never wavered from the firmness of its core yet able to navigate the musical nuance with ease. This was particularly noticeable during the opening arias. Throughout “Si puo ballare” Van Horn managed a balance between his imposing sound and the music’s lightness, offering up prickly consonants and very precise and short phrasing; it allowed him to retain the elegance in his singing while emphasizing Figaro’s bitterness. He capped the aria on thunderous high F’s on “Si,” each one stronger than the last; later on when he recaps this section one last time, that last high F was even more brilliant than the two that preceded it. “Non piu andrai” was similarly nimble in its vocal approach, though here we hear Van Horn’s powerful voice resonate firmly and authoritatively, particularly at the end with the repetitions of “Cherubino alla vittoria, alla gloria militar,” each stronger than the last.

Ying Fang was his dramatic opposite in almost every way, but in the best possible of ways. She was nimble, animated, playful, full of energy at every moment. Whenever she was onstage it was impossible not to be completely focused on her. The fact that she was a lot smaller than Van Horn accentuated their different stage presences and yet you always felt that they were in balance with one another; from the opening duet wherein the two seduce one another there was a great level of comfort, the sensuality palpable. The tease at the beginning allowed for the sexual tension to build throughout, making their more intimate moments later in the opera (the wedding, the garden rendez-vous) all the more engaging and intense. Here were two artists who were completely committed to one another onstage even if their voices were oceans apart in terms of color and texture.

Fang had delightful comic timing throughout, none more present than the moment when she realizes that Marcellina is Figaro’s mother. Her first repetitions of “Sua madre” were given with disgust, almost as if she couldn’t believe that she was being gaslit like that. But then as others repeated and confirmed the notion, you could see the transformation, one character at a time. By the time she asks Figaro, “Tua madre,” there was a visible shock in her visage as it finally dawned on her what was happening. In this production, previous interpretations have Susanna jump up and down a few moments later out of joy, but sometimes that action has often felt perfunctory and indicative instead of organic to the scene; it feels like it’s played for laughs. Here, that jump truly earned its laughter because it came at the moment when Fang’s Susanna was finally able to embrace the truth; the fact that Marcellina jumped with her added to the joy of the moment. Vocally, her singing also flourished throughout, a noticeable crescendo in each enunciation of “Sua madre,” which furthered the potency of the scene.

This one section epitomized the level of craft that Fang put into her interpretation throughout. While Figaro gets the opera named after him, Susanna is the true protagonist of the piece. She’s the one with the most to lose and the one (along with the Countess) who makes the vital choices that ultimately change the outcome of the drama. Plus, she shares duets with all the major characters, something no one else gets the honor of. And Fang capitalized on each one of these opportunities, molding her vocal interpretation to explore the differing dynamics. There was a pointedness in style as she took on Elizabeth Bishop’s Marcellina; Fang added a bit of ping to her sound to contrast sharply with the more opaque colors in Bishop’s sound.

In her scenes with the Contessa, and especially in the iconic letter duet, Fang matched Federica Lombardi phrase for phrase. This duet, which has become somewhat of a cliché in the music world, is one of arresting beauty. Its simplicity is easy to overlook, but when given the proper care and love by the artists performing it, the moment can be a transformative one (after all, this is the pivotal scene in the opera, the moment where a plan that will actually bear fruit is hatched); this performance was one such case with both Fang and Lombardi matching their vocal colors and phrasing so well that they were almost indiscernible from one another. It was as if they were one mind. And then there were the scenes with the Count, perhaps Susanna’s most complex as she has to navigate treacherous waters, requiring her to play the game without giving in. Fang, in her singing and acting, toyed with Gerald Finley’s Count throughout, matching his intensity in their duet and the Act one trio, all while expressing Susanna’s guilt and disgust. This was particularly noticeable during the Act three duet where her “Si” and “No’s” were delivered emphatically to convince the Count of her enjoyment while her face expressed something completely different. It made Susanna’s mistaken “No’s” and “Si’s” all the more believable.

What was perhaps the most exciting aspect of Fang’s performance is how her voice seemed to blossom and open up as the night advanced. Mozart’s writing leaves her with lots of lyrical singing throughout, but there’s also a lot of rhythmic and jagged phrasing during the early portions as well. In the latter part, the lyricism takes over and we get her soaring lines in the sextet, the duet with the Countess, and of course, the glorious aria “Deh vieni, non tardar,” which was undeniably the cherry on top of a wondrous night of singing from Fang. Every phrase melted into the other with sweet legato lines. The tenderness of her vocalization gave the moment a tremendous intimacy. She capped that aria with the most sublime of crescendos on a F6 followed by a subtle cadenza to end the phrase delicately. This mirrored her interpolated high note a few scenes earlier when Susanna repeats the phrase “chi al par di me contenta?

Fang has sung in a slew of Met Opera productions (include “Le Nozze di Figaro” back in 2014 as Barbarina), but this is just her second leading role following a 2020 run of “Die Zauberflöte.” Next season sees her take on two Mozart operas, “Idomeneo” and “Don Giovanni;” there’s no doubt she is bound to be one of the standouts of those productions.

Contrasting Couple

Another artist that is bound to continue making waves at the Met for years to come is Federica Lombardi. I admittedly wasn’t so taken with her in my first experience of her singing, which was incidentally in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” as Donna Elvira (next year she returns to that opera as Donna Anna), but subsequent experiences of her artistry (earlier this season in “La Bohème” or on recording) have made that initial encounter a distant memory. Wednesday night’s performance made that review completely invalid – Federica Lombardi was fantastic.

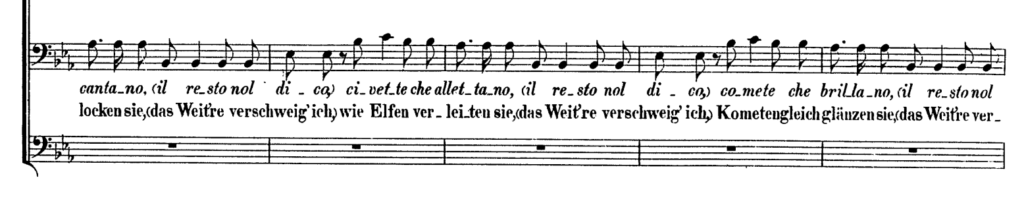

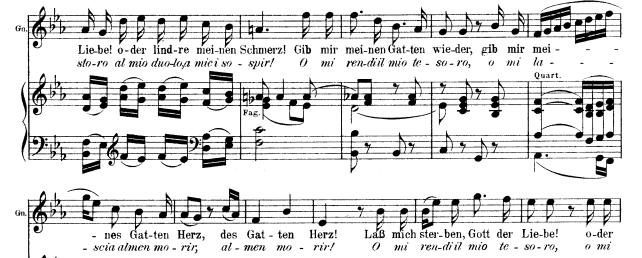

From her opening aria, “Porgi, amor” she displayed an authoritative vocal technique that was simply unmatched. Her opening phrases were glorious piannisimo threads of sound that soared into the house clearly and brilliantly. Every single phrase from there on out blended beautifully into the next, the color consistent, the singing irresistibly precious one note to the other; you could really feel the lament, the pain, the anguish, the need for hope. After a first Act full of fun and games, this was tragedy at its most potent. No moment emphasized the Countess’ pain more than the sixteen note scale at the tail-end of the aria on “o mi lascia almeno morir,” which Lombardi delivered with a potent crescendo, her first forte singing of the night. But you know what made this aria all the more arresting in its beauty? The fact that Lombardi was connecting phrases across a single breath; whereas most singers would take quick breaths during the rests or at the end of certain dotted quarter notes, Lombardi connected the phrases, adding musical tension to the moment and a release and catharsis when she managed to pull off the virtuosic display without a scratch.

She employed a similar approach, perhaps with even more bravura, during the second aria “Dove sono i bei momenti.” That opening line is delivered across four measures with an eighth rest after the second measure. Given how slow the phrase is, most singers take a breath there. Not Lombardi, who by the way, took a rather slow tempo in this aria and somehow expanded the tempo during the repetition, which included ornamentations. Throughout the aria it felt like she was taking a breath every four or six measures (or when there were extended rests), always sounding fresh and in top vocal form. Before the second repetition of “Dove sono I bei momenti,” she added a simple three note bridging cadenza sung with a sublime pianissimo ritenuto that allowed breathing room for the ensuing phrase to feel more expansive and introspective; again, there was a tragic quality to it, almost as if the Countess, in her search for those lost moments of joy, was coming to the realization that they were truly gone and this was her only way to hold on to the little that was left. During the second section of the aria, which shifts into Allegro as the Countess vows to stand up for herself, her singing gained tremendous potency, building and building to a brilliant extended A5 on “di cangiar l’ingrato cor;” on the ensuing A5, she reverted to a threadlike piano sound, crescendoing it into the end of the phrase. Similar beauty was found in her final solo lines at the close of the opera – “Piu docile io sono.” Her singing took on a silky color that floated into the Met auditorium.

Another shining moment of a different variety came during the Act two trio with the Count and Susanna, which features a series of treacherous ascensions to two high C’s; I’ve heard numerous great sopranos falter here or barely pull it off by the skin of their teeth. Lombardi pulled those coloratura runs off without seemingly breaking a sweat.

Lombardi, like Van Horn, is a tall and imposing presence and she made the most of it, standing her ground stoically throughout. It interesting matched Van Horn’s temperament, but also perfectly contrasted Gerald Finley’s Count who was a world of engaging contradictions.

Where Lombardi was still and poised, Finley’s Count, at least in terms of physicality, was quite larger-than-life in moments. He was frantic and emphatic throughout the entire “closet” episode in Act two, delivering a comic gem when the door opened and Susanna exited to find him standing over with an ax seemingly dozens of feet over his head, Finley’s Count frozen in place like a shocked statue. A few moments later, despite seemingly coming to terms with the fact that he made a mistake, he suddenly jumped into action, and rushed over to the dresser and started pouring through it. His gestures were quite big overall, bordering on cartoony in some instances (the opening Act’s trio when he discovers Cherubino under the covers; the realization that Marcellina is Figaro’s mother).

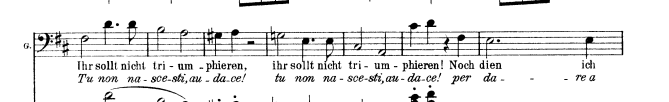

And this choice might not have played so well if not for Finley’s contrasting choice – his vocal approach. Instead of making his singing match his animated characterization, he presented a more restrained vocalization that focused more on subtle nuance in phrasing. There was elegance in every phrase he sang, even when the Count is put into situations where he is made to be ridiculous. His accents, while present, were never exaggerated. His contrast between piano and forte singing was not as potent as that of other artists, but he still gave you enough for them to be clear and present. In a word, it was elegant in its composure. For me, this all came together most affectively in the Act three aria “Vedrò ment’io sospiro,” where the Count is in a rage over feeling duped by Susanna and Figaro. The orchestra thunders at the start of the aria and subsequent phrases build to similar eruptions. You can’t blame baritones who go for broke here and just let their sounds erupt. But Finley, while managing a strong crescendo from the opening A all the way up to the top D never felt like he was trying to “express” the anger. Instead, there was more introspective depth to the aria, a push and pull between the orchestra’s agitation expressing his inner turmoil, and the Count’s need for composure so he can think up a plan to get his vengeance. Here was the Count as a calculator, as a thinking man. He also intelligently saved up his vocal aggression for the Allegro assai section, the staccato phrasing quite pointed; the repetition of this phrase, “tu non nascesti, audace” featured a few more deliberate and emphatic accents on the final quarters of each phrase (to match the bite of the orchestral punctuations), which emphasized the Count giving into his emotions over the reason that dominated the opening lines of the aria.

By the end of the aria, with its triplet coloratura runs and constant leaps into the higher range, Finley allowed his voice to truly boom into the theater; he dispatched the climactic high F sharp with aplomb.

By the end of the aria, with its triplet coloratura runs and constant leaps into the higher range, Finley allowed his voice to truly boom into the theater; he dispatched the climactic high F sharp with aplomb.

Up to that point, one could argue that his vocalism was quite restrained and subtle. But thereafter, you got a greater sense of the monster hiding behind the façade. This was most evident in the garden scene wherein he attempts to win over “Susanna.” Mozart and Da Ponte give the baritone the following lines – “Mi pizzica, mi stuzzica,” which translates to something along the lines of “I’m tingling, I’m feverish,” which of course references his unquenchable lust. Finley made the most of these lines, throwing cautioning to the wind and overemphasizing each consonant; it added a certain lasciviousness to the gesture that suited the characterization of the Count perfectly at this stage in the game. Later on, he bellowed violently as he repudiated the “Countess” and Figaro for their supposed affair. This all allowed for a beautiful contrast at the close of the opera when the Count, completely defeated implores that the “Contessa, perdona.” Here Finley delivered a moment of rich vocal beauty that he hadn’t offered to that point; it was as if we were discovering a completely new facet of the character at that moment, a softness, a vulnerability, a tenderness that had otherwise been lost. In some ways, it matched up perfectly with the vocal approached imbued by Lombardi throughout and provided a bridge between these two characters which were so at odds stylistically throughout the evening.

Populating

As Cherubino, Sasha Cooke had a solid evening. She portrayed him as an awkward teen who lumbered across the stage in the early going, never seeming to know what to do with himself. This was most evident in “Voi che sapete,” where erratic movements (much like Finley’s Count) gave way to poise (much like Lombardi’s Countess) by the second verse. The scenes where Cherubino is dressed up as a girl featured more of the physical discomfort from the character, which contrasted with the uncontrollable gestures throughout the final portion of the final Act. As I noted before, this production makes subtle nods toward the Count and Cherubino as mirrors of one another; Cooke bridged that gap even further with how she had Cherubino accost Susanna in much the same way the Count does.

Vocally she displayed a solid middle range with precision diction and smooth phrasing. It was when she reached into her higher tessitura, especially during “Non so più cosa son, cosa faccio” where there was some noticeable unevenness. This was particularly noticeable with the ascensions to G5, which seemed to be delivered with some caution. There was similar imbalance in “Voi che sapete,” particularly on “Donne, vedete” which starts on an F5 and hangs around that area. That isn’t to say that Cooke didn’t have some truly splendid vocal moments, particularly at the close of both arias. She capped “Non so più’s” final phrases with tender piano sound on “con me.” “Voi che sapete” ended on a delicate diminuendo phrase.

As Barbarina, Meigui Zhang emitted a sweet soprano sound with fluid legato lines throughout her “L’ho perduta,” ending the aria with a beautiful piannisimo high note. She was also quite noticeable in the confrontation with the Count a few scenes earlier, a bright smile on her face and vibrant tone as she essentially blackmailed him into forgiving Cherubino.

As Dr. Bartolo, Maurizio Muraro took some time to warm up (his voice sounded somewhat opaque throughout his opening aria and you felt that he was struggling in the upper reaches of the tessitura throughout), but then found his footing and managed a solid comic contribution to the proceedings. You could tell he was having a blast with Elizabeth Bishop’s Marcellina because, despite being a veteran of this production, he was finding a lot of new moments for the character. Moments after realizing that he’s Figaro’s father, there was one point where Van Horn was presenting his mother to Susanna during the Sextet. Not to be left out, Muraro rushed over to Figaro and reminded him of his presence so he too could get included in the presentation. It was a delightful moment that I’d never seen Muraro add to his interpretation of this production.

Bishop’s transition from overbearing suitor to overloving mother was hilarious to behold; again, you could sense the joy and comfort she had with the other artists throughout their scenes, especially during the sextet where she simply couldn’t stop smiling, jumping about, hugging everyone in sight. It was infectious.

Paul Corona delivered an impressive bass as Antonio while Tony Stevenson’s light tenor added a nice contrast as Don Curzio. In the role of Don Basilio, tenor Giuseppe Filianoti (who sang one of the most memorable Hoffmann’s in recent memory at the Met) added a breath of freshness to Basilio. Often played as a buffoon, Filianoti’s was suave. His tenor, which retains brightness and strength, also gave the character stronger presence than you would get from interpreters that sing this role with a nasal-like mannerism.

As you might have noticed, I quite enjoyed the artistry on display in this performance. Perhaps one final shoutout should go to the casting of this production in particular. On paper these artists could not be more different in approach and yet in execution, it’s this stylistic variety that gave this performance a sense of wholeness that you would never get with strict uniformity.

Categories

Reviews