Metropolitan Opera 2019-20 Review: Akhnaten

Anthony Roth Costanzo, Zachary James Lead The Best Met Production of the Year

By David SalazarPhilip Glass has a solid trajectory at the Metropolitan Opera. Though few of his operas have had major representation at the hallowed house, their scant performances have tended to be major successes, often flanked by fantastically conceived productions that manage to get the utmost of his meditative masterworks. “Satyagraha” remains one of the great achievements in the Peter Gelb era, which is marked by productions often lacking in any sense of creative risk.

“Akhnaten,” which had its world premiere back in 1984, continued this trend on Friday night in an immersive if somewhat draining production by Phelim McDermott that, when the dust settles on the 2019-20 season, will likely remain one of its greatest highlights (it is already, without any doubt, the best Met performance of the 2019 calendar year).

“Akhnaten” follows the rise and fall of the legendary Egyptian Pharoah in his quest to institute a new religion for his kingdom. Of course, his mission ends in tragedy. The opera is unique among many of Glass’ operas as its narrative retains the focus on a singular narrative world instead of shifting its focus as it does between Columbus and a spacecraft in “The Voyage” or Tolstoy, Tagore, and Martin Luther King, Jr. in “Satyagraha.” Of course, like all of those, the opera tends toward more of a ceremonial nature that allows for the composer’s repetitive trance-like music to truly take its effect.

Dramatic conflict is subdued in this work as it is in the other Glass operas, but McDermott managed to created a tremendous amount of visual tension throughout by employing well-placed motifs that become an essential part of the fabric of the story world.

Juggling Act

The main set is made up of three levels – the bottom where we see the pharaohs beings buried and later brought to power; the middle section often reserved for the people, though occupied by Akhnaten and his father Amenhotep III at several junctures; finally, the top section is often occupied by symbolic figures represented by either jugglers or the “Gods.” This division is first noticeable in the opera’s first major setpiece “The Funeral of Amenhotep III.”

This section in particular brings us the first appearance of the visual motif of juggling that will weave itself throughout the work, aligning itself with the rule of Akhnaten. We see increasingly fascinating feats of juggling throughout his encounter with the priests in the temple and especially in the city where the balls being tossed about grow in size with a massive globe (representing the Sun God Aten) as the main backdrop for the set, suggesting the increased power of Akhnaten; even the ghost of Amenhotep gets in on the act at the start of “The City.” What is most impressive and symbolic about the choreography for these juggling acts is the interconnectedness between the different participants; they all form an intricate relationship with one another throughout, the complexity of their choreography growing and growing as they incorporate more and more people into the activity.

This visual motif seems to symbolize the delicate and intricate balance of Akhnaten’s power. His actions are dangerous and one false move could collapse the entire structure he is building for his kingdom. We see these effects in “Attack and Fall” when the jugglers and choral members drop the balls numerous times before picking them up and repeating the cycle. The balls themselves, spread out across the front of the stage, seem to represent “The Ruins” of the opera’s final pages with the figures crawling across the stage pushing the balls to the other side in what can be interpreted as history sweeping aside the impact and memory of Akhnaten’s rule.

This sense of tragedy of time and history’s passing is furthered by the opera’s ending, particularly in a scene featuring a professor trying to teach students about Egypt’s past. The students all line up where the “Gods” and jugglers of the opera’s opening once sat. But instead of a coordinated dance or cooperative juggling act, the students are taking balls of paper and heaving it at one another chaotically. A student throws a piece of paper at the professor as they all walk out; the professor looks on in horror and disappointment.

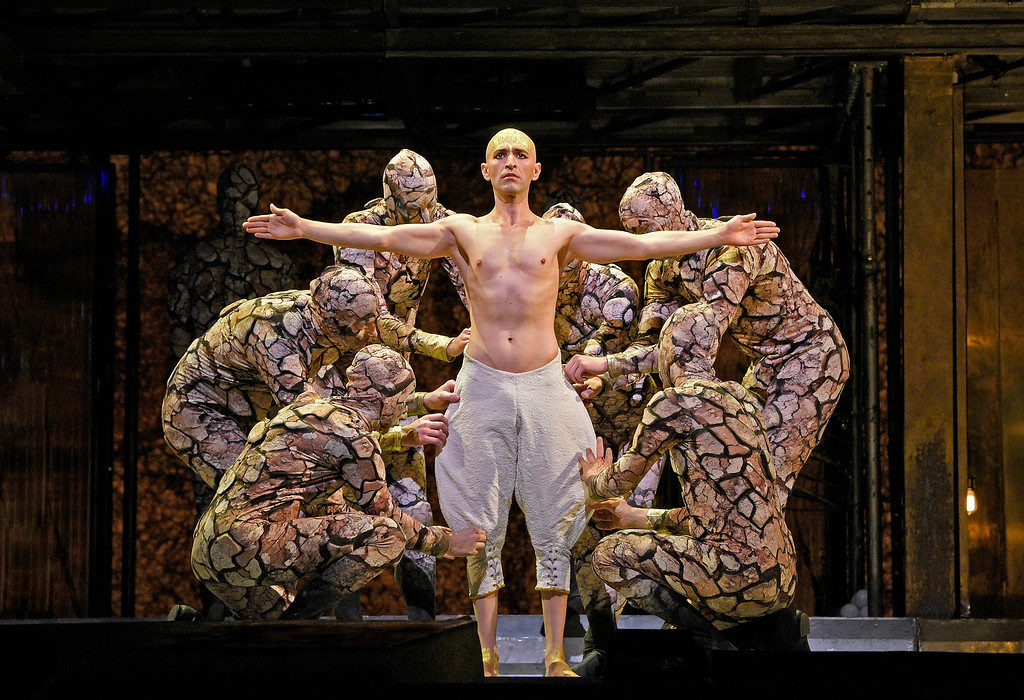

Meanwhile, at the bottom level, Akhnaten is “brought back from the dead” and dressed up in his royal garbs from Act one. Next to him is a sign that reflects his years of rule and nothing more; he has become but a museum piece for no one to watch. This scene resonates potently as it operates in complete contrast to one of the most impressive moments of the opera’s opening. After the death of Amenhotep III, Akhnaten emerges completely naked from what looks like a robed cocoon; he descends slowly to the lower level, gets lifted up in Christ-like fashion before being dressed in the very golden robes that reappear at the close. Where the opening “Coronation of Akhnaten” is ceremonious spectacle to behold, the epilogue’s bookend is tragic in its emptiness.

The opera thus ends on a note of somber melancholy; Glass’ arpeggiated music does not deviate from its perpetual rhythmic emphasis, but the emotions, as contextualized by the staging, allow for deep reflection on how society often lets the past die and even kills it if we need to.

(Credit: Karen Almond / Metropolitan Opera)

Ladders, Red Threads, Uniformity

Other moments of visual splendor and immersion include the use of ladders and frames as expressions of Akhnaten’s rule and fall. Akhnaten descends to be coronated but thereafter, he climbs up a ladder to take his place at the very center of the stage to praise the sun god Aten. He climbs that very same ladder at the close of his hymn, also to his God. A large white frame repeatedly appears throughout the work, often as a portal for the ghost of Amenhotep III to communicate through. At the close of the opera, it becomes the portal through which the priests of old arrive to kill Akhnaten.

The opera employs slow motion action as well with the actors moving very deliberately from moment to moment, allowing for the audience to be able to scan the larger tableau without missing a beat. The use of this technique was particularly effective during “Attack and Fall” where Akhnaten’s daughters are captured by the fierce crowd. Akhnaten runs after them, his mouth agape with fear, but the slow motion suspends the moment and makes him all the more powerless; dramatically it might have been the most effective moment of the night.

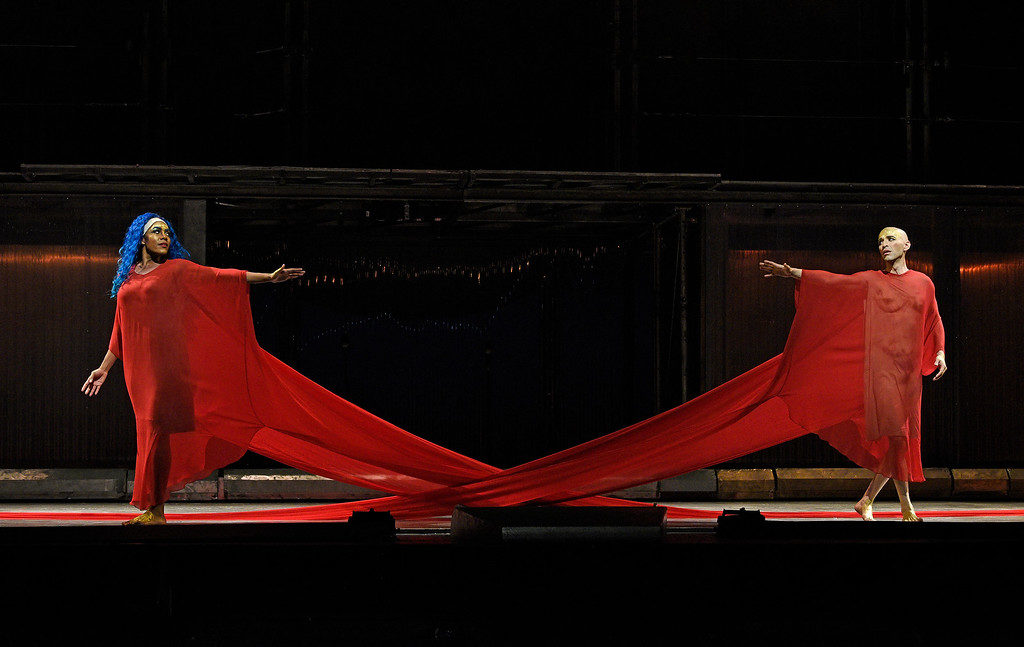

An act earlier, McDermott provides the audience with a hypnotic love scene between Akhnaten and Nefertiti in which the two slowly walk across the stage toward one another. They both drag a long red train behind them with their union at the center of the stage connecting the two into what looks like a limitless red thread, an eternal symbol of destiny and love.

Akhnaten’s religion is marked by a uniformity of dress with the characters often sporting the same outfits; this contrasted with how the priests of the old religion were dressed in differing attire. This was most prominent in “The Temple” where Akhnaten and his followers enter in turquoise and white suits, while the High priest of Amon and his acolytes are all dressed in different attires that range from Gold, Black, and a darker green. This seemed aimed at exploring the concept of monotheistic for polytheistic religion where the former unifies (visually) while the other divides.

This is an opera that merits repeat viewings simply because of the intricate detail (especially on the glorious costumes) that has been placed throughout; nothing seems wasted and there are undoubtedly several instances where one feels that the music and production were meant for one another.

(Credit: Karen Almond / Met Opera)

A Pharoah And His People

While the opera boasts a great number of soloists, very few get their traditional opera solos. But they all play vital roles in ensembles that while musically repetitive in many instances require the most incredible concentration. So it is only right that they get their well-deserved shoutouts. Among these were several debutants such as J’Nai Bridges, Lindsay Ohse, Chrystal E. Williams, Annie Rosen, and Suzanne Hendrix. Other essential ensemble soloists included Richard Bernstein, Will Liverman, Karen Chia-Ling Ho, and Olivia Vote.

The Met Opera Chorus was also in top form, particularly during the opening “Funeral of Amenhotep III,” which they set ablaze with militaristic energy; the same could be said for the equally excitable “Attack and Fall” where their intensity brought about the emotional conflict of the scene.

Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo took on the title role and was particularly effective in the physical aspects of the role. There is no doubt that even if there are no major physical pyrotechnics on display, the precision of his walks and deliberateness of that execution is truly challenging to pull off; the simplest loss of concentration not only registers for the audience, but also drags them out of the hypnotism that the production strives for. That he managed to retain this immersion throughout the night speaks to his incredible stage presence.

He proved a fantastic stage partner in ensembles, particularly during the duet with mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges, in her Met debut, in Act two, their voices matching one another perfectly. Bridges and Costanzo were similarly united in the final trio, this one alongside soprano Dísella Lárusdóttir, who took on the role of Queen Tye.

Perhaps the only disappointing moment in Costanzo’s performance was the one that was expected to be his finest hour – the hymn. While the countertenor managed a smooth legato overall, much of his phrasing consisted of straight tone on longer notes with a sudden wide vibrato on the end to push out a crescendo; the repeated straight tone to vibrato on the same note approach took away from the connectedness of the phrases even if the crescendos created a sense of striving and opening up. His lower range, especially on such phrases as “Thy rays encompass the land to the very end,” was noticeably soft and the orchestra often covered the countertenor’s lower reaches throughout this section.

As the high Priest of Amon, Aaron Blake displayed his own gentle tenor during the opening of “The Temple.” This opening passage posits a higher line for the tenor, which Blake managed beautifully and delicately. He was often joined by Richard Bernstein, as Aye, and Will Liverman, as General Horemhab.

(Credit: Karen Almond / Met Opera)

Amenhotep III’s Ghost

Perhaps the most powerful performance of the night came from Zachary James in his Met Opera debut. He didn’t get to “sing,” but he appeared throughout to provide the opera’s many transitional narrations as the Scribe. But instead of a random narrator, this production kept James in his outfit as Amenhotep III throughout, emphasizing the dead rulers continued presence throughout his son’s rule and the political tension that can mount between one generation and the next. At the core of this story is Akhnaten replacing the religion of his father with his own, a conflict that was cemented in James’ interpretations of the intermittent text; James thus became the source of the opera’s greatest conflict both internally and symbolically.

There was consistent conflict within him, the readings built with hushed frustration that seemed to grow. There was a rising tension as he read the four letters before the “Attack and Fall,” the conclusion of his speech making way for the high Priests to attack his son. But when Akhnaten died, James picked him up in his arms and delivered a pained reading of “The sun of him who knew thee not has set, O Amon.”

He then returned as an excited professor, his lecture about the ruins coming off as an incomprehensible ramble that tied into the concept of history being dismantled by ensuing generations; it seems that the students were not the only issue here, but also the teacher’s own incomprehensibility.

But James’ role was not at an end as his imposing figure would return one final time at the opera’s close with the final trio. Standing over his son, wife, and daughter-in-law, Amenhotep III, the ghost that haunts the opera and his son’s rule, would return once more in the same manner. Akhnaten could never escape his father’s shadow. James’ performance, coupled with how the production incorporated him, was arguably the greatest masterstroke of the entire evening.

Master in the Pit

Not to be overlooked was the work of conductor Karen Kamensek and the Metropolitan Opera. The opera’s prelude seemed a bit restrained, the orchestra seemingly stuck on one dynamic throughout with the downbeats having a subtle but noticeable accent from the strings that made it all feel overly metronomic; there was barely any sense of emotional shift even when the woodwinds or brass entered and you often felt like you were listening to a recording with the emotional range of a midi file created by a computer program. One might argue that the most important duty of a conductor taking on the music of Glass is to be a perfect time keeper, but the music, as repetitive as it might often feel, has its own symbiosis and the best conductors can really give it a life of its own.

Kamensek did just that from the “Funeral of Amenhotep III” onwards, deservedly earning the biggest applause of the night during the final curtain. The brash percussion that dominates the second set piece creating a sense of uniformity and tension in its pervasiveness. Brass interventions throughout the evening often added to this sense of foreboding, particularly with their syncopation during Akhnaten’s famed hymn. The prelude withstanding, the string section’s arpeggiations sounded like one fluid stream, providing the musical bedrock for the audience’s immersion.

Opera is arguably the greatest art form because it encompasses so many. Unfortunately, this very power is not always on ample display, especially with many of the new productions to grace the Met stages over the past decade. But “Akhnaten” is a reminder of the greatness of opera and its ability to appeal to so many different kinds of audiences at once. Those looking for spectacle will find it in spades with the luxurious costumes and the juggling. Those who want a musical experience will no doubt find much to appreciate from the orchestra, chorus, and overall ensemble’s cohesion. Those looking for great theater in a more traditional sense only need marvel at Zachary James’ immersive performances. Those seeking a dialogue will undeniably find themselves probing and conversing internally with what McDermott has placed very intricately with his collaborators.

The 2019-20 season is still young, but “Akhnaten” undeniably rules at the Met and it may be some time before its audiences see anything of this divine quality.