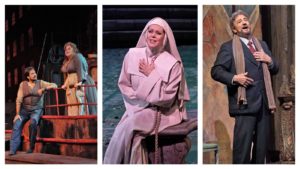

Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Il Trittico

Kristine Opolais Stars On Plácido Domingo’s Big Night

By David SalazarEven before you stepped into the Metropolitan Opera on Friday, Nov. 23, 2018, you knew who the star of the night was destined to be.

The entire marketing campaign run by the Metropolitan Opera in anticipation of “Il Trittico” had seemingly focused on one person and one person only. The company had announced a special ceremony would take place at some point during the performance. A leaflet inside the programs confirmed it later.

Friday night was a statement and reminder that for 50 years, Plácido Domingo has transformed and still reigns as King of the Opera World. Lots of singers sustain careers of 50 years, but few do so the way Domingo has.

On Friday, he reminded the entire Metropolitan opera audience of why he remains the King.

While he didn’t sing until close to 11:30 p.m. (the performance of the triptych started at a bit after 7:30 p.m.), he loomed over the proceedings. After the performance of “Il Tabarro,” the red curtain came up to reveal a video screen. Suddenly a clip from Domingo’s “Esultate” in “Otello” from the late 1970s flashed onscreen. It was followed by a few other clips (out of chronological order, mind you) of other performances before images of his roles over the years flashed on the screen. For a celebratory video, it seemed rather muted with no testimonials or remembrances of what 50 years from the legendary figure were actually like.

Then the man himself stepped onstage to rousing ovation; I don’t think there were many people that didn’t stand. Met Opera general manager Peter Gelb came into the spotlight and presented Domingo with a piece of the stage and a jacket that Domingo wore in a production of “Otello,” now awash in gold. Then Domingo took the microphone, thanked the audience, the Met, and his wife and family for the support over the half-century. It was gripping moment and undeniably felt like witnessing a major piece of history. I am sure that people would have paid just for that, even if the video left a bit to be desired. Gelb also made mention of and spotlighted other major stars and colleagues in the audience (Martina Arroyo, Teresa Stratas, Sherrill Milnes, and James Morris) and it would have been nice to see them onstage with other colleagues performing that evening sharing the moment with Domingo. Of course, one understands that the stage was being prepared for the second opera of the evening and compromises undeniably had to be made.

Of course, there were also some performances, including Domingo himself at the end of the night in “Gianni Schicchi.” But all in due time. Let’s go back an hour or so.

Part One – Verismo in Hell

“Il Trittico” is often interpreted as an ascension from dark to light and with the clear Dante reference in “Schicchi,” it is often seen as a Divine Comedy of sorts. Given that it was written in the midst of World War I and premiered at the end of the great conflict, who knows how much Puccini might have been impacted by seeing the world torn apart and then “brought back together.”

“Il Tabarro,” a work set among lower class folks about a broken marriage and a murder, is undeniably the darkest of the three works; hell so to speak. Jack O’Brien’s picturesque production, with its steamy red colors definitely explores the passion and intensity of the work, but also its gritty and dirty nature.

It looks beautiful when the curtain rises and the audience’s approval was undeniably expected as conductor Bertrand de Billy actually let the applause die down before commencing with the opera’s subtle opening notes.

Unfortunately, the beauty of the production was little more than superficial because the staging could not be any more disjointed. I think all I have to do is go to the end. Michele, the owner of the barge discovers his employee Luigi coming aboard to have an affair with his wife Giorgetta. When Luigi confesses to the affair, Michele strangles him to death and hides him under his titular cloak.

George Gagnidze, playing Michele, and Marcelo Alvarez, Luigi, looked rather awkward during the murder scene, the former wrapping the rope around the latter but looking to be rather careful as to not hurt him. It happened with such little intensity that you might have missed the action altogether. When Alvarez’s Luigi actually died, he didn’t collapse but knelt down and seemingly stayed in place without falling forward or to the side; gravity was thus defied. For something that was attempting to be realistic in its approach, this bit of acting simply took you out of the story at the most crucial moment.

But this was but one moment. The intimacy between Luigi and Giorgetta registered about as passionately as that of Michele; the point is that Michele and Giorgetta’s marriage is on the wane while the relationship between Luigi and Giorgetta is on the rise. That we couldn’t differentiate between the two is rather telling.

Acting styles also didn’t quite match up. Where Alvarez used a ton of hand gestures to emphasize his emotions, Gagnidze and soprano Amber Wagner were more still and naturalistic in their styles. Of course, every artist has his or her own way of doing things, but differing performance styles make the story itself lack in a sense of consistency or general point of view.

Vocally, the performance was solid, though far from riveting.

Alvarez was appearing in his 20th anniversary performance with the Met after making his debut on Nov. 23, 1998 in a performance of “La Traviata.” He had struggled with vocal troubles in the last year and had canceled performances of “Tosca” last spring as a result. He appeared on stage on Friday, but vocally he also seemed to lose some of the brightness and beauty. He actually got off to a solid start with “Hai ben ragione; meglio non pensare,” with a vicious and intense interpretation. Since taking on heavier repertoire, the Argentine tenor has had a tendency to push a ton at the top and accent notes and phrases to give an impression of power and intensity and compensate for some of the lighter qualities in his lyric tenor. With this particular passage, those choices worked quite well and gave Luigi a sense of desperation and powerlessness.

However, he retained this same style throughout the entire night. Luigi, of course, is no suave romantic, but even in his duet with Giorgetta, their two voices coming together for glorious lyricism, the tenor continued pushing at the top. By the time he got to the visceral “Folle di gelosia!” with the tenor tessitura rising and rising in intensity as Luigi grows in violence, you could sense that Alvarez was pushing his voice to the brink. And since we had already heard similar phrasing throughout the evening, it made this intense moment somewhat fall flat.

Gagnidze’s harsher vocal colors definitely worked well for Michele as a beaten-up blue-collar worker. He was best in his long scene “Nulla!… Silenzio!” even though his voice seemed underpowered in the climactic moments of the passage; the orchestra, despite seeming a bit restrained on the whole, covered his singing at its most potent. And despite the darker, grainier sound, there was a limited range of emotional palette in his singing; harshness in the murder sequence was similar in color to his plaintive lyrical lines with Giorgetta during their scene together. The extensive solo scene allows the soloist ample time to explore his own psychology from insecurity, to anger, to a deep pain over rejection. Gagnidze never quite moved beyond the sense of anger, ultimately taking away from the story’s potential impact for truly immersive and complex beings.

Amber Wagner sang beautifully, and her vocal performance was undeniably the highlight of “Il Tabarro.” Everything just sounded very much in her vocal wheelhouse and she pumped out one gorgeous sound after another; top notes were assured, and it was just pleasant to hear her. Even though Alvarez and Wagner matched one another well note for note in their duet, it was her sound that dominated and her silky legato that really came through in that moment. She made it sound easy.

But her characterization also seemed lost at sea. We didn’t get a sense of her desperation or her need for Luigi over Michele. That her life was boring or uninteresting really never came to light in any emotional way. Her scene with Frugola, where we witness two women dreaming of something better, didn’t really register as much more than one woman exchanging jewelry with another.

One might sum this up to the fact that all of the principal artists in this production were making role debuts. Everything in this opera happens at lightning speed so details in direction become all the more paramount; this is likely where the ultimate challenge was with this opera and the fact that it came off as dramatically inert.

In the pit, Bertrand de Billy seemed to be playing it safe with tempi. It’s a tempestuous piece, but the ebb and flow of its emotions never quite surfaced from the pit, even if the playing was always exact and quite precise. But there was a clear sense of restraint and a feeling that the conductor was trying to be supportive of his singers rather than pushing them on and working in tandem to create an emotionally potent drama.

Part Two – A Shining Light in Purgatory

Puccini loved “Suor Angelica” more than any of his other operas in this trilogy. Ironically, this is the one that has not had quite the critical lovefest of the two works that flank it. Part of the challenge really is that this opera is one big emotional crescendo that places all of its dramatic and emotional weight on the central figure in a rather short period of time. If the soprano does not rise and build the opera’s intense emotions in a manner that rivets the audience, the opera flounders. No one else can save “Suor Angelica,” literally and figuratively.

On Friday night, you could see why Puccini loved this opera so much and the emotional intricacy that he worked so hard to build. And Kristine Opolais was the reason why.

The Latvian soprano was singing in her 50th Met Opera performance and sixth role (fifth by Puccini) and this might have been one of her finest nights in that hall. The great challenge of this opera is how much information is hidden from the audience in the opening minutes of the opera. Angelica remains but a fringe character until halfway through when the Princess shows up. When she does, we are given a plethora of information on who this nun is and her painful tragedy.

Going from just another nun to a tragic figure in just minutes is a challenge for any actress. Often, sopranos go from being anonymous in the story suddenly blasting one big sound after another in the second half’s intense emotional moments; but there is no build and hence the opera remains in purgatory.

But Opolais managed it quite well. The staging helped a bit as well, keeping her central throughout the exchange with the Princess. While Stephanie Blythe’s princess was a stone-cold and immovable object, Opolais’ Angelica was more vulnerable, her body collapsing ever slowly throughout the exchange. While her voice retained a muted quality in the early parts of the exchanged, the shift toward conversing about her son betrayed increased emotional intensity. What you saw and felt was the conflicting natures of a mother while all the while seeing the nun trying to pay her respects to the venue of the conversation. This inner conflict, combined with the emotional intensity of revealing Angelica’s great tragedy, added nuance to the situation. You might often find sopranos start to really throw caution to the winds in this section emotionally, but with Opolais you sensed the inner turmoil more acutely. And because of this, you felt drawn deeper into her performance, wanting more and wondering whether we would get it.

And she did give us more, though it came about gradually, the tension sustaining throughout. The portamento “grido lamentoso” right after this scene came about as rather charged emotionally, the first real moment where Opolais started to expose the pained inner life of Angelica.

“Senza mamma,” the opera’s famed aria would seem the appropriate moment to just let the soprano push her voice to the brink emotionally; Puccini’s arching lines ebb and flow throughout the aria, though he does ask for “voce desolata.” Opolais took an introspective approach to the aria, giving it an intimacy and privacy; you couldn’t help but feel pulled more and more into her orbit.

It also kept you guessing about where Angelica might go next emotionally; you sensed her deep pain, but we couldn’t yet predict a sense of desperation. It was a believable choice, given that she’d been a nun for years and on some level, one might understand Angelica having discovered coping devices for her difficulties. The preparation of the poison thus felt like a discovery of character and her own shock at the realization that she was damned also came off as a genuinely potent.

It was here that Opolais took off her “veil” and succumbed to intense desperation. Her voice soared and even if you might have gripes with some coarser sounds in her upper vocal reaches, you simply couldn’t argue against the complete emotional immersion. The climactic high C was a piercing cry of the despair and the two final downward portamento G naturals were gut-wrenching.

This was undeniably one of the best performances that Opolais has given on the Met stage and it would have been rather fascinating to see the soprano’s immersive interpretation on camera, where many of her subtler gestures would have revealed more about her approach to this character.

The performance was elevated further by the austere Blythe whose long phrases at the start of the conversation between the Principessa and Angelica had a cold lifelessness to them. However, as she walked out and turned slightly toward Angelica, there was a sadness in her face. It was a confusingly potent moment. Was she sad to see Angelica’s pain over her son’s death or was the sadness disappointment in Angelica? These are the questions that engage you further with the drama and elevate it.

There’s no doubt that the acting in this particular production was likely left to the devices of its central artists, and it was all the better for that. The production itself is markedly basic in its design, taking place in the garden of a convent. However, there were some major issues with the production’s greatest special effect – the light transforming day to night throughout the performance. At some points, the shifts were faulty and abrupt, taking the viewer out of the experience. One imagines that such technical miscues will be cleaned up across the run.

De Billy and the Met Opera Orchestra seemed far more engaged and in synch with Opolais throughout this opera, sculpting this hour-long emotional crescendo perfectly. He might have lacked brutality and a sense of raw human pain in “Il Tabarro,” but the cleaner orchestral colors added a greater sense of reverence and overall immersion to the world of “Suor Angelica.”

Part Three – Not Quite Heaven

The opening bars of “Gianni Schicchi” were vibrant and propulsive; you might even suggest that the tempi were rather quick, providing a jolt from the slower-moving “Suor Angelica.” The energy was certainly there in the orchestra throughout the final opera in Puccini’s “Trittico,” though onstage, it was more of a mixed bag.

This opera can be one of the most enjoyable experiences anyone can have on an opera stage. It cuts to the point with fun character dynamics and riveting melodies. But with a rather large ensemble cast, staging is all the more tantamount. “Tabarro” revolves around three central figures and “Suor Angelica,” despite its large group of nuns, really comes down to letting one person run the show.

But that’s not the case with “Gianni Schicchi.” Every character, from the eponymous anti-hero to the doctor Spinelloccio or even the young child, are crucial to creating the world of Puccini’s comic gem.

O’Brien’s production plays up the theme of stage-within-a-stage with the Buoso’s room taking place within another stage that will later be brought to our attention when Schicchi himself breaks the fourth wall. The room is rife with furniture and despite its sense of order, we also intuit the potential for chaos.

But we never quite get there. For despite moments where people run around the stage either attacking each other or pulling the room apart, it never quite built to a sense of abandon. For example, as the characters seek out Buoso’s final testament, they “pull apart” the room, except they kind of don’t. Actors picked up props and then set them nicely on the ground and perhaps picked up another. The sense of desperation in finding this essential document never felt quite as urgent as one imagines it should be.

Ditto when Schicchi throws everyone out of the room. They admonish him, but never truly engage with him or attempt to chide him in any manner. They just got cheated out of their own fortune and yet they didn’t quite feel that angry; the result was also that Schicchi’s own indignity with them was rather tame as he threw them out. All of this intensity provides for incredible comedy that bubbled but never quite boiled.

Domingo was in strong vocal form throughout and you couldn’t help but marvel at the fact that at 77, his voice still produces the sounds it does. There are undeniably moments where lower notes in the score simply weren’t audible in his voice (particularly low E flats and D’s where he seemed to revert to a more parlando style). But in the center of his voice and even in some of the higher reaches of the tessitura for the opera, he retained a solid core, the vibrato taut and poised. Where most singers might understandably have to deal with a wobble at that age, Domingo’s voice doesn’t seem to know what a wobble is. The sound rang beautifully and his legato line, particularly in “Addio, Firenze, addio, cielo divino” was fantastic.

Domingo isn’t much of a comedian as his career has been devoted almost exclusively to tragedy, so he didn’t really draw as many laughs from the vocal quirks or text layered throughout the opera. In vocal terms, his interpretation of Buoso wasn’t quite differentiated from his Schicchi. Puccini’s score asks for “voce nasale e accento Bolognese.” One can’t fault Domingo for not producing a perfect “accento Bolognese,” but he didn’t really try the voce nasale at all. The sudden shift is a hilarious effect, and it would have been even more so with an iconic voice like Domingo’s. But the choice to not engage with Puccini’s markings left an interpretational void in the impact of these scenes. More of Domingo’s comedy gold came from his physicality, such as his response to “O Mio Babbino Caro,” where he looked to the audience and gave a shrug that said, “What can I do after hearing that?”

It wasn’t Domingo’s most compelling or complete interpretation, and yet you couldn’t help but feel riveted just from continuing to hear him sound as good as he does. That’s what transcendent artists do.

The rest of the cast also put in solid shifts. Soprano Kristina Mkhitaryan had a solid debut as Lauretta (it is worth noting that aside from Domingo’s big night, there were a plethora of other debutants on this evening, including Brian Michael Moore, Sharon Azrieli, Leah Hawkins, and Jessica Faselt). Her sound isn’t particularly large in its projection, though it did the job in this role with an elegant “O Mio Babbino Caro.” That said, she didn’t do all that much in building any interaction with Domingo onstage. Lauretta doesn’t really get much stage-time, but the famed aria, where she is begging her father to help the family and, by extension, help her, is a moment that can definitely allow a window into the father-daughter dynamic. After all, moments after her aria, this head-strong man gives in and does what she wants despite his own indignation. Domingo managed the moment well, though the payoff would have been all the better with a stronger setup from the soprano.

Tenor Atalla Ayan pulled off his aria “Firenze è come un albero fiorito” handsomely, though some of the higher notes on closed vowels at the climax of the aria sounded a bit pushed and underpowered.

Of the remaining family members, Gabriella Reyes and Stephanie Blythe were the undeniable standouts vocally, their singing always capturing the attention at different intervals. Blythe just knows how to take her space when she can and her interactions with Domingo were among the more comic ones on the night. Reyes’ flirtations with Schicchi were also quite engaging, the soprano taking a seductive approach to the character of Nella. That said, you couldn’t overlook the remainder of the ensemble at all with Maurizio Muraro, Lindsay Ammann, Patrick Carfizzi, Jeff Mattsey, Tony Stevenson, Betto di Signa, Kevin Burdette, Philip Cokorinos, Scott Conner, and Christian Zaremba, all working as perfect team players toward bringing the comedy to life.

The hope is that with each coming performance, they will light up the stage to truly hilarious effect.

In all, Puccini’s “Trittico,” in its 100th year, is something you simply can’t miss. The music is just that good and Opolais’ “Suor Angelica” and Domingo’s voice are worth the price of admission alone.