Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Aida

Anna Netrebko & Anita Rachvelishvili Remind Us That They Are On Another Level

By David SalazarVerdi’s “Aida” is the quintessential opera in so many ways. It features a larger than life story in an exotic world alongside some of the greatest music ever written. In a house like the Met Opera, this work is also featured in an impressive and immersive set tailored to bringing us to some version of Ancient Egypt. This current production by Sonja Frisell has been around for quite a few decades. It’s quite the definition of static, though the visual beauty often makes one forget that the singers are doing little else but parking and barking. However, oftentimes we get casts that only remind us all the more of this lack of dynamism onstage.

The production is reportedly on its way out, so it is fitting that one of the final casts to give it the send-off would be one of such high quality as the one on Wednesday, Sept. 26, 2018. It was one of the most anticipated performances of the entire season and it certainly didn’t let anyone down.

One of the main attractions was Anna Netrebko’s first interpretation of the lead role at the Met; she is reportedly going to take on the opera again in an upcoming season, but in a production tailored to her dramatic potential. This is great news, because a soprano as dynamic as Netrebko, capable of making anything out of nothing, often looked like she wanted more to work with onstage in this production. She didn’t often get it, but she made the most of what she could. And she did quite a bit and then some.

Rising Above the Challenge, As Per Usual

Aida is a challenging sing and the Russian diva was not at her most comfortable in early passages, her sound a bit unsteady in the opening trio where Verdi challenges her with soaring lines over the more rhythmic vocalizations of the Amneris and Radamès. But by the ensuing scene, she was warmed up and ready to charge forward, her sound piercing through the massive ensemble. “Ritorna vincitor” is a challenging aria, not only vocally, but because it demands the soprano to really give us a sense of the duality existing within Aida. She loves Radamès, but she feels a strong sense of loyalty to her home, which she misses. Just in the first two lines, we sensed the torn nature. She blasted out “Ritorna Vincitor” with full-blooded conviction before her answer, “E dal mio labbro usci l’empia parola” had a coarser quality that expressed her repudiation of the former phrase. This ruggedness, which expressed exasperation and dread, continued throughout this recitativo section before transforming into an agitated distress on the rising and falling “L’insana parola o Numi, sperdete!” High note climaxes vibrated brilliantly, each one with greater and greater sense of pain and resentment. But the key of it all was the final “Numi pieta,” the voice floating quietly, prayer-like. She extended phrases amply and the importance of this interpretation was made all the more brilliant during its callback a few scenes later after the heavy-hitting confrontation with Amneris. This scene was arguably THE best scene of a night filled with many of them, but seeing these two women operating on such a high dramatic and vocal level was simply divine in the truest sense. Netrebko went from humble and gentle to growing in frustration over the course of this dialogue and her reprisal of “Numi pieta,” left alone to wonder her fate, was hard-edged and rougher; you could feel the anger boiling up in Aida as well as her resentment toward the gods for leaving her behind. This theme of an absent God is a vital one in all of Verdi operas and it was great to see it brought to life in this manner, but at the end of the day this is what makes Netrebko so great – she provides unique dramatic insight into everything she does.

The third Act is Aida’s with the character forced to face her dueling temptations more directly. Netrebko is best when she is playing off someone just as immersed in the dramatic situation and this was best exemplified in her duet with Quinn Kelsey, where she sparred with him. Often one sees Aida submit to her father rather quickly, but Netrebko was fierce in her rejection and even bitter in her “O patria quanto mi costi!” In the ensuing duet with Radamès, we saw a new facet of the character, that of seductress, her singing taking on a more sensual quality as she demanded they leave Egypt. In the context of the preceding emotional duel with Amonasro, seeing Netrebko as feisty and aggressive really drove home the sense of connection between father and daughter; it also played to tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko’s strengths in a rather aggressive take on the Egyptian hero.

If there is one thing to note about Netrebko’s third act is that “O patria mia” was far from her shining moment, though she managed the aria well overall. However, she did seem out of breath in parts, particularly when the singer is asked to sing “O patria mia” across two measures in the upper range, crescendoing all the way to a high A. You felt that Netrebko might not make it, and while she did, you wondered how she might manage other more challenging passages to come. She did quite well the rest of the way, the High C coming through potently in the hall. The thunderous applause that resonated after she completed the aria was undeniably deserved.

True Operatic Royalty

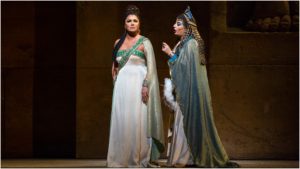

And while Netrebko had a wonderful night, one might argue that Anita Rachvelishvili stole the show from her co-star. The Georgian mezzo was simply perfect in every single moment she was onstage, looking and sounding like an Egyptian monarch all the way through. At only 34, it is astonishing that the mezzo has already accumulated not only such a collection of challenging interpretations but has managed them with the artistic maturity and insight that many dream of but never achieve even after decades and decades of performing. It makes you wonder about what is to come in the decades to come; she’s certainly on her way to be one of those singers we continue talking about for decades and perhaps centuries to come.

Her singing in this role was simply divine. When in the presence of Radamès or singing about him, as is the case at the start of Act two, the mezzo’s voice had a delicate, soothing quality. “Ah! Vieni, vieni, amor mio” lies in a tricky spot for any singer to start (the first note is a high G for a mezzo), but Rachvelishvili’s election for a gentle onset not only suited her perfectly but gave the music richness and life. Similarly, her sublime “Sì! Io pregherò che Radamès mi doni tutto il suo cor,” might have been the single most beautiful piece of singing an evening full of it. It was pure rapture with a tinge of innocence and vulnerability that we were, to that point, not allowed to see in Amneris. For the first time, we saw Amneris, not as a domineering and spoiled princess, but as a young girl with dreams.

But when she had to turn up the fire, she surely did. The duet with Aida moved from sardonic delicacy to full-on trumpeting of sound. It’s not easy to overpower Netrebko’s massive instrument, but Rachvelishvili did just that. Every phrase was filled with so much passion and anger, that it felt like she was dropping punches on her rival by the second. Her physical presence in this scene was imposing, the mezzo standing tall and firm and just letting her singing do the work. She was all the more potent in the final act where Amneris must showdown with the high Priests to save Radamès. After putting everything emotionally and vocally into the duet with Radamès, you wondered how much Rachvelishvili might have left in the tank for the final phrases, which incidentally use up all the mezzo range Verdi could muster. The answer was always inevitable, with the mezzo putting all the strength she could into those phrases, the struggle of the powerless character visceral. As she threw out her pleas, we could feel the agony, immersing us in every single word and sound that came out of her mouth. The climactic phrase “Empia raza” that closes the scene was tackled with accented voice, only added to the character’s tragic nature, her sense of anger, fury, and guilt all coming to the fore. The climactic A was both a cry of pain and rage.

Beauty & the Beast In One

Quinn Kelsey is quickly establishing himself as the Verdi baritone of our time. Last season he was imperious as the Conte di Luna at the Met, but his Amonasro was truly a beast of nature on so many levels. From the first moment he opened his mouth in Act two, you could tell we were in for a great evening of singing from the Hawaiian-born singer. His voice has a richness and purity of sound that when combined with the heft he is capable of resonating beautifully in the hall. His delivery of “Quest’assisa ch’io vesto vi dica” had nobility in the beauty of his sound, but the accented and rougher edges of his phrasing betrayed the anger and warrior who is Amonasro. His relationship to Netrebko’s Aida certainly swayed between loving and border-line abusive, his aggressive nature with the simple “Non mi trader!” instilling fear instantly. But he really highlighted this duality in the famed duet, his singing at the start of the duet “Rivedrai le foreste imbalsamate” oscillated between manipulative and caring in how his singing caressed and yet pressured Netrebko’s Aida; there was a sense of urgency and forward movement in the gentle phrasing. Of course, most wonder how any singer can manage the furious “Su, dunque! sorgete, Egizie coorti!” which demands vocal power and versatility from the baritone at the same time. Most times we get the one without the other, the text often lost in the volcanic sound that a singer might usher up in the moment. But here Kelsey kept it all intact and we could feel every word like a dagger to Netrebko’s Aida. It built and built with rage, the beauty of Kelsey’s sound replaced with a coarser quality that was frightening to behold. It all climaxed in that famed parola scenica “Non sei mia Figlia! Dei Faraoni tu sei la schiava,” which the baritone extended for all it was worth. It added even more intensity to the scene and the momentary stillness that followed left palpable tension in the air. Then we got the caring Amonasro to close the duet and this time you could feel that the baritone’s full immersion in beauty of line expressed a deeper empathy with his daughter. Verdi singing doesn’t always have to be aesthetically beautiful, because when a singer taps into a combination of aural and dramatic beauty, we get the transcendent quality the great master always dreamed of. Kelsey, alongside Netrebko and Rachvelishvili, did just that.

Not to be overlooked were basses Ryan Speedo Green and Dmitry Belosselskiy, who also made their respective presences felt throughout the evening. The latter really worked at the darker and grittier nature of Ramfis, every phrase almost a rigid decree. This was most notable in his icy attitude toward Rachvelishvili’s Amneris in Act four. Speedo Green was gentler as the Pharoah, particularly in presenting Amneris as the future wife of Radamès at the close of Act two.

But…

Unfortunately, not everyone had a night to remember. Back in 2011, I went to Carnegie Hall for a performance of “Otello” with Riccardo Muti conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko sang the lead role in one of the finest interpretations of the heroic character in recent memory.

That seems quite the distant memory at this juncture as the promising voice from seven years ago is a mere shell of itself. At 43, the Latvian tenor has volume and squillo in the upper register, but his singing had no elegance or refinement, his phrasing seemingly all about finding a way for him to pounce on a climactic note with all the strength and power he can muster. “Celeste Aida” is one of the greatest challenges in the repertoire and Antonenko made it sound like a massive chore. The opening melody, “Celeste Aida, forma divina” rises up an octave to an F natural, right in passaggio for the tenor. Antonenko didn’t carry the line consistently, throwing off a massive and weighty accent on the last note that had a shouty quality to it; it didn’t really seem to connect in the least with the five notes that preceded it. His singing throughout the aria would progress in this manner, entire phrases leading to a powerful accented note that didn’t feel part of the rest of the phrase. The high B flats that Verdi layers throughout the aria resonated throughout the theater, but they weren’t the kind of sounds one could relish, but more like hammer blows. Antonenko’s ascension to the climactic B flat at the close of the aria (“un trono vicino al sol”) lacking any resonance or vibrato to speak of. He seemed unsettled by it as he didn’t sustain the note much and just simply threw it away with all the strength he could at the end.

One tends to give a tenor the benefit of the doubt after this aria because it is so challenging and comes without the singer getting a chance to warm up. But Antonenko’s singing, and particularly his phrasing, didn’t really change much over the course of the night. One might argue that as a warrior, he wanted to show force and strength throughout his vocal interpretation, but he came off as a brute and one had to wonder what any of the two leading ladies saw in this man that was worth fighting over. There was choppy phrasing throughout the duet with Aida in Act three and while his anger toward her in the ensuing trio during his lines “Io son disonorato” were surprisingly refreshing from a character standpoint, it wasn’t enough to overlook the rest of the evening. The final scene of the opera is perhaps the most challenging for Radamès interpreters, the tenor asked to sing mostly pianissimo throughout. And it was not surprising that Antonenko, who seemed to feel most comfortable singing forte, struggled most in these sections. “Aida, dove sei tu?” is written dolcissimo with a slight rise to an E natural. Most tenors rise to that note, hold it longingly and then descend smoothly to the rest of the phrase. While it isn’t what Verdi wrote (the E natural is but a quarter note with no fermata), it’s a lovely piece of interpretational tradition. Of course, Antonenko is not beholden to it, but his decision to forgo this turn of phrase sounded more like vocal discomfort with the demands less than an interpretational decision. He sang with fil di voce throughout “O terra addio,” but his sound, bereft of its voluminous potency, sounded frail and arid; you could make the argument that the sound emulated the character’s dying breaths, but his decision to interject certain phrases with blasts of accented sound would not support this argument.

One thing worth noting in the tenor’s favor is that he didn’t show any signs of tiring the entire evening, his vocal enthusiasm and power was sustained throughout. It was the most disappointing performance of the evening by far, not to mention a blemish on an otherwise perfect evening.

Ups & Downs

Conductor Nicola Luisotti had a solid night in the pit, though consistency was not his game. The opening prelude had a sense of propulsion, but the combination of winds, brass, and strings heavily favored the brass sound, which created a sense of aural imbalance. Verdi counterpoints the brass playing the priests melody with Aida’s in the string, but the latter sounded rather muddled, the overall orchestral effect metallic. The ballet in the second Act seemed overly heavy, the dance never quite taking flight and always feeling weighed down by the orchestra. Another moment that left me wanting more was the violin ascensions at the climax of Aida’s “O patria! Quanto mi costi.” The violins crescendo can be so overwhelming as to be gloriously unbearable, but the restraint shown here made you feel as if a door was slammed shut in your face just as you were about to walk through it. But then there were moments of pure wonder and exhilaration, such as when Luisotti let the orchestra go wild during Amonasro’s famed “Su, dunque! sorgete, Egizie coorti!” If you want to feel what anger and fury really is, that was it. In other moments, he sped up the tempo, giving the music even greater sense of urgency; this was the case during the soloists’ entrance at the close of the second Act. There were also refreshing moments of breath, such as the end of the opera where a sudden pause right before the high B flat from the violins four measures from the end of the work. Those final bars were bliss and it was rather disappointing that the audience interrupted the final note with applause (though to be fair, the timing of the curtain dropping has always been the culprit that we never get to hear Verdi’s glorious final moments as he wrote them).

Where would we be without the Met’s chorus, who put in a third straight night of brilliant singing. Act two is the big scene for the ensemble and the waves of oceanic sound energized the listener.

All in the all, this could be seen by many as a historic night. The two dueling divas re-established their greatness on the Met stage in one of the iconic works of the repertory. This production gets a Live in HD performance in a week and one hopes that any of the factors that were not on the level improve so that that broadcast can be one to savor for decades to come.