MasterVoices 2022 Review: Carmen

Ginger Costa-Jackson & Terrence Chin-Loy Headline Incredible Performance of Bizet’s Original Vision

By Chris RuelPhotos: Erin Baiano

If you were to walk down a street, stop a stranger, and ask if they’ve heard of the opera “Carmen,” more than likely, many would say yes. Ask the follow-up question: What’s it about? There may be some head scratching and faces scrunched in concentration as they try to recall … “Bullfighter.” Whether it was in an opera house or on television as a comedic vehicle for Bugs Bunny, “Carmen” is a known quantity far outside of the lofty circles of opera cognoscenti, and that’s fantastic. It’s a work that leaps over the barricades of stuffiness.

And, if you take in the original Opéra-Comique version, you will not hear recitatives, but dialogue, and a healthy dash of comedy, making it lighter fare geared toward a broad audience very much in the vein of popular musical theater.

Bizet and his co-librettists Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy adapted Prosper Mérimée’s novel of the same name. The composer left the exoticism of oriental settings for Spain, where Gypsies lived wild and free, smoked many cigarettes, engaged in smuggling, and threw fists readily. However, with female sexuality on full display, violence and the murder of the hero were bridges too far for the directors of Opéra-Comique Du Locle and De Leuven, particularly the latter. “Carmen,” in De Leuven’s view, was inappropriate for a family opera venue. Eventually, he resigned, fed up with Bizet’s vulgar project. Du Locle didn’t like the realism.

The opera opened to less-than-stellar reviews, which got under the composer’s skin. On an early June night, the curtain went up for “Carmen” for the 33rd time. Bizet died the same day. Opéra-Comique presented “Carmen” 48 times. Bizet’s composer contemporaries heard and saw something they thought was a masterpiece.

The Most Popular Opera in the World

On October 25, 2022, New York’s prestigious MasterVoices presented the work admired by Massenet, Wagner (!), and Brahms. According to the program notes, Tchaikovsky was an unabashed fan of the opera, stating, “‘Carmen’ is a masterpiece in every sense of the word; that is one of those rare creations which expresses the efforts of a whole epoch. … I am convinced that in 10 years, ‘Carmen’ will be the most popular opera in the whole world.” How prescient; at the Metropolitan Opera alone, “Carmen” has been staged over 1,000 times.

What is it about this work that so enthralls? The music certainly carries a lot of water. When leaving the theater, how many of us have hummed, whistled, or vocalized the famous Habanera or “Votre toast,” a.k.a. the “Toreador Song”? In that regard, it’s akin to “La Bohème,” with its catchy takeaway numbers, but you can also understand why Wagner was pleased; Bizet used motifs—three highly recognizable motifs—that a casual listener can readily associate with characters and actions. The Prelude to Act one hands these themes to the audience, starting with the corrida from Act four before the music segues into the “Toreador Song,” and finally, the ominous “fate” theme.

Then, there’s the story itself which gives performers and directors a wide berth to try fresh approaches. “Carmen” is a mezzo’s dream, and rarely do performers mimic those who have sung the roles prior. A singer can play Carmen as a libertine sex pot, an object lesson of a morality tale, a strong, liberated woman unbound by cultural and sexual mores, or a good-time girl who gets involved with the wrong guy. And there are so many other possibilities. That, in itself, makes the opera interesting no matter the times one might see the show. Likewise, Don José can be a bumbling country dolt; a tempestuous man-child; an obsessed, jealous guy with a nasty temper; or an utterly pathological and dangerous individual.

The shock factor (at least in the 19th century) cannot be downplayed, though we may no longer find aspects subversive. Remember, Du Locle and De Leuven at Opéra-Comique were adamant Bizet should dial things back, even suggesting that Carmen should not be murdered at the end. We can also view the story as proto-verismo, whose primary composer, Puccini, had no issue writing dark, tragic operas that can rip a heart in half. There are no kings, queens, princesses, or wealthy landowners. “Carmen’s” characters are nobodies, except for the famous bullfighter Escamillo. Don José is a lowly corporal; Carmen, a gypsy; Micaëla, a country girl, and a not-so-dynamic duo of smugglers.

Simply put, what’s not to like?

Nothing Short of…

MasterVoices’ semi-staged presentation of the original Opéra-Comique version was nothing short of spectacular. Everything came together. Tony Award-winning conductor, and MasterVoices Artistic Director Ted Sperling, who has paced Broadway shows, operas, and symphonic music, led 100 or so chorus members, 30-plus members of the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, and 17 singer-actors performing behind him in a knock-your-socks-off rendering of the score. The principals, Ginger Costa-Jackson (Carmen), Terrence Chin-Loy (Don José), John Brancy (Escamillo), Mikaela Bennet (Micaëla), and Leo Radosavljevic (Zuniga), crushed their vocal and spoken lines. Gustavo Zajac’s entrancing choreography blended modern and traditional dance, with flamenco taking center stage, and Brian Tovar’s lighting dramatic light design and Ann Beyersdorfer’s scenic design showed the power of simplicity.

Sammi Cannold directed a mostly family-friendly show that captured the potency of Carmen’s desire and the violence of her death without going overboard. The more unseemly aspects of the opera coalesced late in Acts three and ran through all of Act four when Don José’s jealousy turns him into a monster, and Carmen faces her demise. Acts one, two, and part of three have comedic moments; the scenes are lighthearted and jocular before things turn dark.

Sheldon Harnick’s English translation of the spoken dialogue was clever and charming. Harnick has translated works by Stravinsky, Mozart, and Verdi into English. But more so, Harnick, along with his late partner composer Jerry Bock, was the team behind wildly successful Broadway shows, such as “Fiddler on the Roof.” His translation brought the opera’s humor to a non-French-speaking audience and, by doing so, flung the door open to the mysterious world of opera and one of its most enthralling stories.

The Cult of the Bull

Haze filled the Rose Theater auditorium, creating a soft, dream-like space. At center stage, a spotlight illuminated a dancer dressed in black and sporting horns. She lay curled up on a round platform. The horns didn’t look like those of a bull, but of a mythical creature.

In ancient mythology, Hothar was the cow goddess, horns and all. A cow is not a bull, but connecting Hothar to the dancer isn’t far-fetched. Several cultures established Bull cults. In Egypt, the bull deities were Apis and Mnevis, the Canaanites had Moloch, Aaron cast the Golden Calf of Biblical lore, and King Solomon had twelve brazen bulls.

Fast forward a few millennia, and we encounter Ernest Hemingway’s book, “Death in the Afternoon,” which remains one of the most highly regarded guides to bullfighting, informing readers of the players, the meaning, and the symbolism behind the ceremonies. Hemingway explains a quasi-religious experience as the matador and bull engage in a dance of death full of graceful veronicas and molinetes.

Hemingway writes, “… the bullfight is very normal to me because I feel very fine while it is going on and have a feeling of life and death and mortality and immortality, and after it is over, I feel very sad but also very fine.”

With this as context, the “bull” centered and prone on the platform could be a sleeping god or a noble, dead beast.

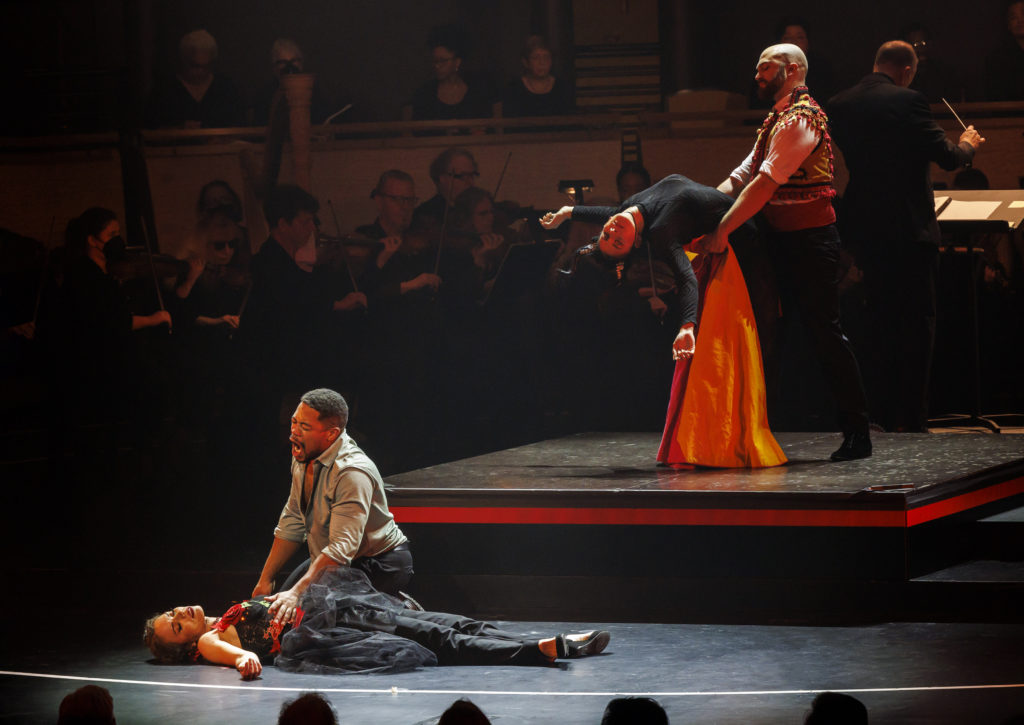

The MasterVoices presentation brought forward the connection between Carmen and the doomed bull. On stage, as Escamillo fights his bull, Don José fights Carmen. A blade kills both. Gustavo Zajac choreographed the dual action in a way that made the parallels pop.

Allegro Giocoso

Ted Sperling burnt rubber with the Prelude. It’s a tune we all know and have heard countless times in various settings—cartoons, commercials, parodies—but nowhere near the speed for which the score calls. So, when we hear it played at speed, it feels too fast. It’s not. Bizet marks the tempo allegro giocoso with ♩= 119. To put that in perspective, the tempo rule of thumb for popular dance music is ♩= 120.

Sperling had a lot going on. In front of the podium, there were 100 singers to conduct in three tiers of stalls and a large orchestra on the ground. The principals and ensembles had to be tight because Sperling never turned around to give a cue. The singers had to feel it, instinctually. It didn’t always go accordingly. Twice, the onstage singers and orchestra were a smidge off, but this was readily fixed.

The conductor brought verve and sharpness to the score while keeping things organic and not robotic. Bizet’s score, like Carmen, is a wilful bird that needs the freedom to fly, which makes fun work for a maestro. Of course, it wasn’t always that way. Musicologist Hugh Macdonald relates that in 1875 the Opéra-Comique orchestra struggled to grasp Bizet’s style, and Du Locle made known his bewilderment at the music. Yet, a century and a half later, the world hums its melodies.

Orchestras performing “Carmen” get their share of the limelight and instruments, too. The first violin and cello get their moment in Act one, and in Act two, the winds take the solos with the English horn setting up Don José’s “Flower Song,” while the flute also has fine moments.

The entr’actes between Acts one, two, and three provide another opportunity for the pit to shine. The entr’actes—often played as preludes—director Sammi Cannold and choreographer Gustavo Zajac turned into micro ballets, and that’s where we’ll go next.

Stomping to the Beat

Dance drives “Carmen.” There’s the “Habanera,” the “Seguidilla,” the “Castanet dance,” and the “Gypsy Song,” all of which are integral to the story. Zajac used three dancers, Isaac Tovar, Camila Cardona, and Laura Peralta. Cardona was the bull mentioned earlier, while Tovar and Peralta presented the audience with thrilling flamenco. The dramatic zapateado (foot stomping) was so well-timed with the orchestra it became an integral part of the band’s percussion. The two dancers are ninja-level castanet players whose artistry leaves you speechless. In Act two at Lillas Pastia’s, Tovar and Peralta entertained the bar’s patrons and the Rose Theater audience, as well.

As the bull, Cardona’s moment came during the finale. As Don José attacks Carmen, a similar scene occurs in the dance’s movements. The dancers stylistically slaughter the bull the moment Don José knifes Carmen. In Sammi Cannold’s show, empathy for Carmen is equally distributed to the bull. The bull, while not omnipresent, was a constant reminder of the tragedy to come.

Dancers Laura Peralta and Isaac Tovar. MasterVoices presents Carmen, Ted Sperling, conducting Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Sammi Cannold, director, Gustavo Xajac, choreographer, Ann Beyersdorfer, scenic designer, Nicole Slaven, costume designer, Brian Tovar, lighting designer. Credit Photo: Erin Baiano

Carmencita

As stated earlier, there is no true Carmen. One mezzo plays the vamp, while another highlights Carmen’s firm sense of self. Ginger Costa-Jackson’s performance in the title role stole hearts as the beautiful gypsy. Her Carmen was an amalgam: she was strong and independent; she was a sex magnet; she was snarky and sarcastic; and possessed a quick wit.

With dialogue, the performers had to act in the manner of stage-play or Broadway musicals. Some did this better than others. Costa-Jackson did it the best. She was the genuine star of the show. She radiated energy, both comic and tragic. There is plenty of room for many great Carmens, and Costa-Jackson should be added to the list … And we have yet to talk about her voice.

Carmen needs more than a great voice, she must have personality. Costa-Jackson imbued her plush, velveteen voice with the same spirit that drove her acting. Her voice was mature, secure, and strong. It easily filled the auditorium with a gorgeous sound. Her lower range bordered on contralto with its deep sound, while her top notes, such as in the habanera, were rock solid.

Carmen’s entrance—while the cigarette factory girls puff away—was full of swagger, her mannerisms sultry, and her overall demeanor exuded confidence. She sang “Habanera: L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” with playfulness, enjoying the game she starts with the dumbstruck, lascivious soldiers, and Costa-Jackson’s performance of “Seguidilla: Près des ramparts de Séville” was full of joy and verve.

The two hit numbers gave ample room for the Chorus to strut its stuff. Volunteer singers comprise the massive gathering of 100 voices who pushed out a glorious wall of voices with each chorus. Just to hear such a thing was well worth the price of admission.

Carmen’s death scene was convincing, not only from the strident, obstinate tone but for the manner in which she dramatized Carmen’s final breaths. There was nothing stylized about it. Her head lolled back, her eyes stared blankly as her body went slack, and her mouth was open like a fish gasping for air.

While the closing moments of the opera are serious, high drama, and full of unrestrained emotion on both the part of Carmen and Don José, most of the show was breezier and light in no small part to Costa-Jackson’s comedic sense while acting and singing.

Ginger Costa-Jackson as Carmen. MasterVoices presents Carmen, Ted Sperling, conducting Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Sammi Cannold, director, Gustavo Xajac, choreographer, Ann Beyersdorfer, scenic designer, Nicole Slaven, costume designer, Brian Tovar, lighting designer. Credit Photo: Erin Baiano

Don José

The second powerhouse principal was tenor Terrence Chin-Loy. The tenor had the range required, as well as the vocal stamina. Switching from singing to speaking is tiring. Don José doesn’t start singing until halfway through Act one, almost 25 minutes into the show.

Chin-Loy is a spinto tenor, very lyrical, but showed he could go dramatic when needed. Pairing Costa-Jackson’s darker, spinto voice with Chin-Loy’s brighter sound was a solid choice. Like pairs mesh best, but there are always exceptions to rules.

Acting-wise, Chin-Loy’s Don José was a bumbling soldier who wanted to be good, but his lust led him astray. He’s a puppy Carmen plays with. But as we know, Don José grows homicidal in his jealousy. Chin-Loy spun Don José from an aw-shucks country guy to a homicidal maniac slowly, building the character’s instability scene by scene until things go tragically sideways in Acts three and four, rather than revealing his darker side earlier on.

The takeaway number for Don José is “La fleur que tu m’avais jetée,” commonly known as the Flower Song, and it’s a tenor favorite. Chin-Loy sang it with heartrending sweetness, quiet passion, and beautiful phrasing.

Interestingly, while Don José rages and threatens Carmen during the Finale, Chin-Loy made it seem as if the murder, while not an accident, wasn’t entirely intended. The question has been raised at various times: Did Don José intend to kill Carmen, or did he ultimately want to win her back? If the latter, he needed to reconsider his approach.

Ginger Costa-Jackson as Carmen and Terrence Chin-Loy as Don Jose, foreground, dancer Camila Cardona and John Brancy as Escamillo on platform. MasterVoices presents Carmen, Ted Sperling, conducting Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Sammi Cannold, director, Gustavo Xajac, choreographer, Ann Beyersdorfer, scenic designer, Nicole Slaven, costume designer, Brian Tovar, lighting designer. Credit Photo: Erin Baiano

Escamillo & Micaëla

Grammy Award-winning baritone John Brancy’s Escamillo was a hoot as he played up the toreador’s vanity and rock star status. Returning to Hemingway, in his roman-à-clef novel “The Sun Also Rises,” Jake Barnes is an aficionado who takes his ex-pat pals to a bullfight to see one of the bravest matadors in all of Spain and had this to say: “Nobody ever lives their life all the way up except bullfighters.” Escamillo proves Barne’s notion.

The “Toreador Song” is forever a crowd pleaser, and Brancy played the brash hero of the corrida to a T. The bullfighter basks in the glow of himself; he’s the coolest kid in school, and everyone wants to be his friend or girlfriend—including Carmen, though not at first.

Brancy’s tangling with Chin-Loy in the fight scene between Escamillo and Don José was tense. Brancy is a powerhouse baritone—deep and full of thunder, and his voice meshed nicely with Chin-Loy’s smooth brassiness.

Bizet’s bullfighter punches above his weight; his limited stage time and his vain antics have an outsized effect on the audience, and Brancy seemed to love every minute. The audience certainly loved him.

Here’s a question to pull out at your next opera trivia night: According to the program notes, In order to soften the opera for Opéra Comique audiences, Bizet made some changes, one of which was changing Lucas the picador into Escamillo the toreador. He also introduced a new character, Micaëla.

Virtuous, kind, and unsullied by the world, Micaëla is the anti-Carmen. However, juxtaposition isn’t the only thing at play. The story gives little information about Don José’s home life. Through Micaëla, we learn he has a sick mother. He doesn’t return to his mother despite pleas from those around him because he is madly in love with Carmen. There’s a pattern here. Judging by his behavior, Don José has no sense of responsibility. For Carmen’s love, he deserts the army; he deserts his mother, and he deserts Micaëla, crushing her heart.

Mikaela Bennett played an endearing Micaëla. Bennett crushed the audience’s hearts with her sweet, songbird-like voice that was as gentle as her character. Her devastated reaction after having her heart stomped on showed every ounce of pain her character experienced. There couldn’t possibly be a more sympathetic figure than Bennett’s Micaëla.

Leo Radosavljevic’s Zuniga was not a hardcore lieutenant, though he wasn’t amused by Don José’s behavior. Radosavljevic presented a half-serious character. He might not be the sharpest guy in the army, but that doesn’t make him less dangerous. Yet, his commitment to capturing and jailing Don José and Carmen was half-hearted. He knew where they were, but he, too, was enjoying the women and drink at Lillas Pastia’s. Of course, when does attempt to arrest the two, they foil him. Radosavljevic has a robust and pleasant baritone, not as heavy as Brancy’s, but carrying enough authority for the role.

MasterVoices presentation hit on all cylinders–great singing and acting from all, breathtaking dancing, a gargantuan chorus, a top-notch orchestra led by a masterful conductor, and fascinating lighting design and atmosphere. And, though the props were simple, and the sets equally so, MasterVoice’s “Carmen” was passionate, charming, funny, and crushingly tragic.

MasterVoices presents Carmen, Ted Sperling, conducting Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Sammi Cannold, director, Gustavo Xajac, choreographer, Ann Beyersdorfer, scenic designer, Nicole Slaven, costume designer, Brian Tovar, lighting designer. Credit Photo: Erin Baiano