LA Opera 2018-19 Review: La Clemenza di Tito

Russell Thomas & Elizabeth DeShong Shine In Mozart’s Humanist Opera Seria

By Gordon WilliamsEven before the curtain rose on this Los Angeles Opera production of Mozart’s “La Clemenza di Tito” which I saw on March 7th, 2019, I was excited by what I had read in the program booklet.

LA Opera Music Director James Conlon’s article, “Clemency, Forgiveness and Love” with its emphasis on Titus’s closing message that “I know everything, absolve everyone and forget everything” alerted me to the serious issues that underlie this moving portrait of leadership.

Then I got part way through the synopsis and was so impressed by its clarity that I looked to see who had written it. It was the director and scenery designer Thaddeus Strassberger himself. These discoveries augured well for a really insightful interpretation of Mozart’s next-to-last opera and I was not to be disappointed.

Lived In Splendor

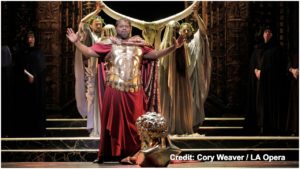

“La Clemenza di Tito” was begun when Mozart was well into composition of “Die Zauberflöte” which, however, was premiered later, at the end of September 1791 (“Tito” had its debut on Sept. 6 in Prague, “Flute” Sept. 30 in Vienna). Unlike the “rough theater” and comedic vigor of “Zauberflöte,” “La Clemenza” is an “opera seria.” The term conjures images of formality, aloofness, and some might say, stiffness. Strassberger’s scenery – evocative of ancient Rome – certainly conveyed an impressive grandeur. At times I was reminded of massive paintings by Tiepolo that can take up the entire wall of a gallery.

The costumes of Mattie Ullrich, who worked with Strassberger on LA Opera productions of “Nabucco” and “The Two Foscari,” were rich and sumptuous, conveying the sense of an elevated milieu. And yet these were clothes to wear.

The production gave off an overall air of lived-in splendor. This was “opera seria” which homed in on the human dimension. (I admit it. I really felt for Taylor Raven’s Annio when ‘he’ ‘manfully’ accepted that he would have to surrender his beloved to the emperor.)

Hooked By the Downbeat

But I was hooked musically from Conlon’s initial downbeat. There was a gripping urgency behind the opera-seria formality, even in those moments when Mozart’s choice of musical style has always struck me as more restrained than I would expect from the dramatic situation.

And partly this had to do with the number of cross-currents of emotion we could observe in play at every stage of this performance. Certainly this was noticeable in ensembles such as the Sesto-Vitellia-Publius trio “Se a volto mai ti senti” which marks Sesto’s arrest, James Creswell’s repetitive “vieni” implacably demanding that Sesto submit to custody. But the big take-away from the production for me was the incredibly detailed motivation in each characterization, even in solo numbers.

Manipulator and Manipulated

As Vitellia, Guanqun Yu was a very manipulative operator, palpably impatient at her lover Sesto’s failure to follow through on his promise to kill Titus, whom she perceives early on as an enemy. She was sarcastic, hysterical. The vocal detail of an aspirated “di” on “Addio” perfectly conveyed her contempt for this disappointing lover.

“Command me as you wish,” Sesto lamely replied, or words to that effect, and I noted down, “Poor guy; she’s got him around her little finger.” Then I remembered that Sesto was being played by mezzo-soprano, Elizabeth DeShong, Her strong mezzo – a constant delight to listen to – provided a nice irony to the haplessness of the character she was portraying.

By the way, DeShong’s was one of two very impressive fake beards in the production. The other belonged to Sesto’s friend, Annio (played by Taylor Raven, as mentioned before). To describe Sesto and Annio as “trouser roles” might these days be thought to downplay the seriousness of these parts, but I really believed I was looking at men, and the blend of DeShong’s and Raven’s mezzo voices in the duet “Deh prendi un dolce amplesso,” pledging continuing friendship, was a touching highlight of the show.

And DeShong’s Sesto kept drawing my attention. The big Sesto aria, “Parto, parto,” was exceptionally well done, with DeShong’s closing coloratura perfectly conveying Sesto’s delirious happiness at being granted Vitellia’s merest favoring glance. Actually, much of the aria was delivered to Vitellia’s back, one of many examples of Strassberger’s excellent clarifying staging.

But the moment that most convinced me of the vividness of this production was the Accompanied Recitative “Oh Dei, che smania è questa,” Sesto’s description of the train of destruction just unleashed in Rome. I could see it all and then I realized, “There’s no-one but Sesto and nothing else on stage at this point.” It was all done in the voice and orchestra. Credit to the violins and oboes for their successful creation of a breathless hocketing effect. Mind you, after interval the smoking scenery denoting ruin attracted a deserved round of audience-applause.

As Publius and Servilia James Creswell and Janai Brugger respectively brought great vividness and supportive stability to their comprimario roles. And then we come to Russell Thomas’s Titus.

The Emperor

You might expect that there would be something monumental in this lynchpin of a character, and yet Thomas showed us the emperor’s vulnerability, even down to eagerly rushing forward in the manner of a pleaser when he suggests, in his opening recitative, that tributary gold should be spent on helping the victims of Vesuvius’s eruption. I found Thomas at his most riveting in his rage but particularly loved the ringing tone of his final pronouncement of clemency. We could follow the pathways of his character’s thinking. Thomas gave us a trajectory we could follow.

They all did.

Guanqun Yu’s Vitellia was visibly rattled, for example, when she learnt that Titus had chosen her, instead of Servilia, for wife. Up close you could see the forced smile drop, but the “putting a good face on the quandary” was also in her voice.

The chorus, prepared by Jeremy Frank, made itself felt at vital moments. The hair stood up on my neck when they blared out “tradimento” at the end of Act one. I immediately thought of Verdi’s concept of “parola scenica” and also of how smart it was to emphasize this concept at the midpoint of a show which will close with Titus’s nobler concepts – “tutto so, tutti assolvo, e tutto obblio.”

In the past week, I have been lucky enough to see both of Mozart’s 1791 operas only days apart. I saw Pacific Opera Project’s “Magic Flute” last Saturday. I could easily pull out a recording of the Requiem, to cap off a week of late Mozart’s masterpieces. But I don’t really need to, to bask in the opportunity I have had to reflect on the fortunate (for us) coincidence of opportunities that allowed Mozart in his last summer to compose two of the three final works that summed up his humanistic outlook on life.