Gran Teatro del Liceu 2017-18 Review(s) – La Favorite

Clémentine Margaine Makes A Strong Case for Donizetti’s Oft-Neglected Courtesan To Return to Favor

By Jonathan SutherlandApart from the onslaught of syphilis, 1840 was a good year for Gaetano Donizetti.

He become the first composer to have three operas (“La Fille du Régiment”, “Lucrezia Borgia,” and “La Favorite”) debut in three different theaters in Paris within a period of less than 12 months. The last of the trifecta was written specifically for Rosine Stolz (née Victoire Noël) who apart from being a celebrated mezzo, was also the mistress and literally “favorite” of the Director of the Académie Royale de Musique, better known as the Paris Opéra.

“La Favorite” was an immediate success but its popularity never really passed into the 20th century after a later, much more schmaltzy Italian version (“La Favorita”) gained greater acclaim. That said, “La Favorite” has all the usual 19th century ingredients – brooding monks, indolent ladies of the court, contemptible courtiers, a loveable courtesan, philandering monarch, potent prelate and an unhappy but religiously uplifting ending.

An Unfavored Work

Librettists Aphonse Royer, Gustave Vaëz and later Eugène Scribe played fast and loose with 14th century Castilian history and instead of King Alphonse XI’s consort being the daughter of the King of Portugal, Donizetti’s unseen Queen Maria becomes the unlikely offspring of the Supérieur du Couvent de Saint Jacques de Compostelle, aka Balthazar. The real ill-fated maîtress d’honneur didn’t enjoy an operatic demise in the arms of her beloved but was actually murdered on the orders of Queen Maria after Alphonse died.

Musically the score is variable but has a lot of instrumental depth and several strong dramatic scenes. According to musicologist Julian Budden, Donizetti’s legendary speed in composition was in overdrive in “La Favorite” with most of the last act written in an implausible four hours. Although generally faithful to the original French text, director Derek Gimpel opted for the revised verismatic Italian dénouement. Instead of the monks leering over Léonor’s body and Fernand making the ominous prophecy “Et vous priez pour moi demain,” the tenor gets a crack at another top C and Pagliaccio-like, wails the seemingly obvious “elle est morte.”

Gimpel’s direction was competent without being particularly inspiring although Jean-Pierre Vergier’s al fresco stage designs were visually memorable in a minimalist “The Name of the Rose” meets “El Cid” fashion. The monastery of Saint-Jacques resembled a massive granite rock closer to the Shinto Meoto Iwa, but the island scene was interesting due to a small single-sail cog ferrying the smitten ex-novice, which glided beside the crowded jetty without having to tack or maneuver at all. The Jardins de l’Alcázar were bereft of blossoms or blooms and looked more like the bear caves at the Madrid Zoo. The nuptial chapel was another hole in a rock.

Dramatic characterizations were never more than superficial with the dastardly Don Gaspar having the menace of the Dalai Lama. Vergier’s costuming was more successful with some colourful robes for the young ladies of the Court although a few towering conical wigs suggested the grandes dames of Castile went to the same hair-stylist as Marge Simpson. The Benedictine habits were more taupe than traditional black and as a novice, Fernand should not have had a cuculla. His oversized wooden cross was closer to a redneck rood and Balthazar’s OSB’s pectoral crucifix similarly more costume Catholic than Cluniac correct.

In fact Fernand spends a lot of time taking on and off various chains. On first leaving the Order, he tears off the rustic cross which Léonor replaces with a much more sumptuous gold chain holding a porcelain cameo of her good self. On being elevated to Marquis de Montréal, Alfonse XI gives Fernand a gaudy livery collar closer to a local Lord Mayor’s carcanet, but on finding out that Léonor is in fact the King’s mistress, this precious decoration gets ripped off and cast to the floor as well. The toast of Tarifa would have been even more miffed had Scribe included the fact that Alphonse had ten children with Eleanor de Guzman.

More Favorable Musical Aspects

There was much more to enjoy on the musical side with Houston-based conductor Patrick Summers making welcome restorations of the usual cuts, in particular the extended ballet music which although not in correct order, was spared the distractions of cavorting Castilians or leaping Leonéses. Admittedly this music is not the finest Donizetti ever penned, but the instrumental interludes provided the opportunity for some impressive solos, especially in the winds. Overall Summers was able to elicit some very fine playing from the Orquesta Sinfónica del Gran Teatre del Liceu and from the first warm cello passages, it was clear that the Indiana-born maestro had a very firm grip on both partitura and players. There was real marcato bite at the allegretto mosso tempo change in the overture and the frequent dynamic shifts between fortissimo and piano were scrupulously observed. The tricky contrapuntal concertante sections such as the finale to Act Two and peppy “Grâce, ô roi!” section in Act three were rhythmically tight, although the vivace “Déjà dans la chapelle” ensemble came close to losing synch between pit and stage. Tempi were generally uncontroversial with some well-measured rubati, but Summers was also prepared to let the motivated musicians off the leash when required. First flute was plaintively persuasive in “Léonor, viens” and the solo trumpet opening Act two and cor anglais and cello introduction to Act four were particularly solid. Brass were especially effective during “Ô mon Fernand” and “Ange si pur” and the electric organ used in the last Act had a surprisingly convincing churchy resonance.

Mixed Messages

As usual at the Liceu, there were two casts for most of the principal roles. In the non-alternating parts, Roger Padullés didn’t provide a unique perspective of the diabolical Don Gaspar in either vocalization or characterization. Donizetti was anticipating a Barnaba or Iago but Padullés villain was more like Gounod’s valium Valentin. Miren Urbieta-Vega was an adequate Inès and handled the lilting “Rayons dorés, tied zéphre” with confidence if not always purity of timbre. The cadenza to top Bb was slightly heavy but the crescendo-diminuendo on the concluding F natural “l’amour” pristine. The zippy “Doux zéphyr, sois lui fidèle” had the requisite delicatezza and the final sustained A natural was potent. Gimpel’s direction of her violent abduction by Gaspar was little more than popping into a rock cupboard.

Croatian bass Ante Jerkunica was a permanently scowling Balthazar. In the opera libretto he is also both King Alphonse’s father-in-law and Papal legate with a vested interest in keeping the unfaithful monarch’s marriage in tact. Jerkunica sang some sepulchral low F naturals such as “ne te maudisse pas!” and “Toi, mon fils, ma seule espérance” had portentous solemnity. Top E flats were solidly supported but there was minimal impact at “Arrêtez les effets, chrétiens!” Jerkunica would have benefitted from more legato and less hoot.

The role of the bigamous “el Justiciero” Alphonse was shared by Mattia Olivieri and Markus Werba with the former easily taking the laurels. Olivieri’s good looks were not exactly a liability, but his ability to shape a Donizettian phrase with a warm, honey timbre was even more impressive. The Italian baritone’s top register was particularly strong with some wonderful high F naturals and immaculate trills at the end of the “Jardins de l’Alcázar” scena. “Léonor, viens, j’abandonne” was masterfully delivered with mellifluous legato. Werba was not entirely without merit and his fury in “Redoutez la fureur d’un Dieu terrible” was incendiary but the Austrian singer’s intonation tended to spread and his French diction was generally poor.

Not American Favorites As Fernand

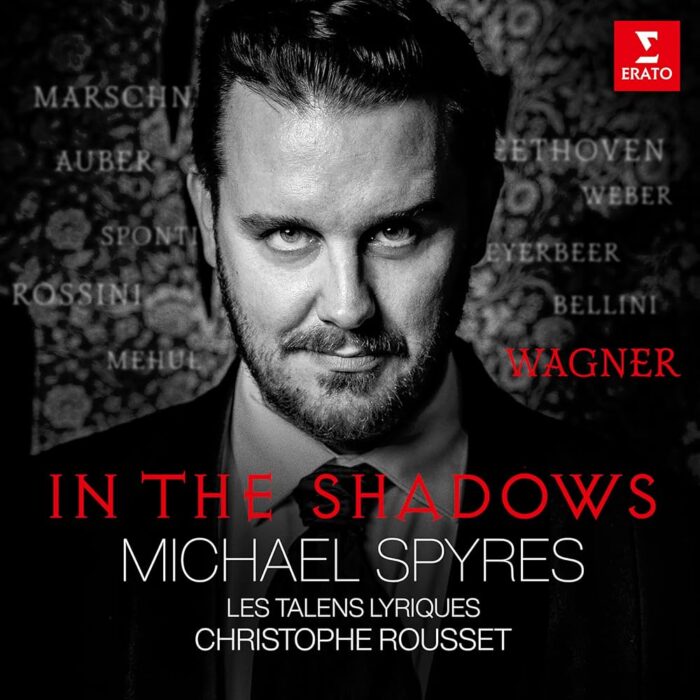

Neither American tenors Stephen Costello nor Michael Spyres were really satisfactory in the part of the besotted novice Fernand. Both paid limited attention to the dynamic markings, with the piano change on “je priais” in the opening recitative for example being ignored, although Spyres made a lovely piano fermata on “un autre destin!” On the other hand, he seemed to lose projection above top A-flat and there was a tendency to push, which caused a displeasing bleat. Costello was more ingénue in characterization but it was difficult to imagine either singer as capable of arousing the interest let alone lust of the wordly Léonor. “Un ange, une femme inconnue” creeps up to a top C-sharp on “elle” which both tenors took with more gritty determination than vocal dexterity. An interpolated G sharp trill leading to the resolution tonic was technically better executed by Spyres, but the martial “Oui, la voix m’inspire” cabaletta was sung at a gutsy gallop by Costello. The man from Missouri was more confident in the extreme upper range but an original cadenza on “Où puis-je être heureux?” rising to another top C was more strained than symphonious, as was another interpolated high C at the end of the duet on “heureux.” By the “Ange si pur” cavatina, Spyres’ upper range was markedly labored and the climatic top C on “envolez vous” and following cadenza was far from stellar. The A natural on “Grand Dieu!” was barely intoned, as were the series of following A flats.

The True Favorite

Léonor was actually cast for three different mezzos including the appropriately named Daniela Barcellona at the end of the run. Eve-Maud Hubeaux made a decent enough effort although the lower tessitura tended to be more individual note plucking rather than seamless phrasing. If there was a Premios Princesa d’Asturies for best performance as a cast-off courtesan in a Donizetti opera, it would have gone to acclaimed French mezzo Clémentine Margaine as the ill-fated courtly concubine. This is a singer who has the caramel vocal color of Elīna Garanča with the punch of Fiorenza Cossotto. There was moving word coloring in the semi-quaver runs on “C’est Dieu qui se venge” and the low A on “ne le demande pas” was so resonant it could have come from Davy Jones’s locker. Purred low B’s on “A moi la honte” had plaintive potency and the same tone on “ce serait infame!” had tuba like tenacity. The “Quand j’ai quitte le château de mon père” passage was particularly moving. Léonor’s most important scena “O mon Fernand” in Act three was a tour de force for Margaine with long, admirably controlled phrasing in the largo section before a puissant “Mon arrêt descend du ciel” cabaletta full of dazzling leaps, runs and embellishments with a Simionato-esque top A fermata to close. The French mezzo’s formidable acting skills were evident as the shorn “novice” in the last scene and her sustained octave drop on “Grâce” and later “sous tes pieds écrase-moi!” would have made even the bible-bashing Balthazar more benevolent.

After such an inspired performance by Clémentine Margaine, Donizetti’s 50th-something opera definitely deserves to became “La Favorite” once again.