Dutch National Opera 2019-20 Review: I Pagliacci & Cavalleria Rusticana

Anita Rachvelishvili & Ailyn Pérez Are Forces of Nature In Robert Carsen’s Genius Production

By Mauricio Villa(Credit: © BAUS)

Canadian director Robert Carsen is one of the most solicited directors in every major opera house nowadays and he proved why in his new production of the famous double bill of “I Paglliacci” and “Cavalleria Rusticana,” which opened the opera season at the Dutch National Opera.

It is a production where he plays with theatre-within-theatre concept, making the audience part of his staging and interacting with the public as it has probably never done before in Opera. This idea has been present throughout Carsen’s career often in such works as “Les Contes d’Hofmann” for Paris Opera or “Tosca” for Teatre del Liceu, but in the Netherlands the theme has been taken to the extreme.

Full Audience Engagement

The production opens with “Pagliacci” and as the opera begins, you hear the trumpets and the chorus coming from the back. Using the doors of the auditorium for off-stage chorus or small orchestration has been done a lot. But then a few people from the first two rows stand up, and you realize they are singing; and little by little the entirety of those two rows stand up to sing, interacting with themselves and with members of the audience as they are joined by the rest of the chorus, which is now entering from two back doors and walking down the aisles. It was like a flash mob as they were dressed in regular clothes and they obviously entered the theatre as public with the rest of the audience. It was so surprisingly shocking and magical.

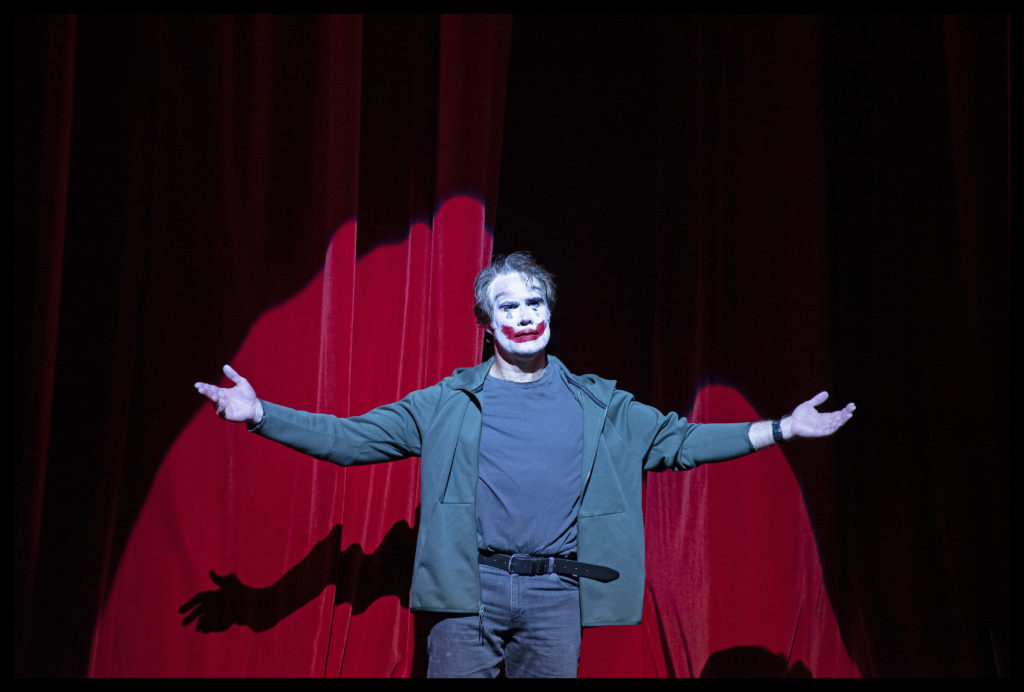

Then the chorus got onto the stage while the company of clowns arrived. On the stage, there is another stage with a red curtain and the leading singers, all wearing clown masks, brought theater elements like mobile hangers with costumes and black square boxes which turned into a dressing room mirror with bulbs.

Surprisingly enough, with the chorus spread around the theatre at the beginning and sometimes even facing the stage, the sound and the acoustics were amazingly good. At some point the theatre on the stage turns around, making you feel that you are backstage. This emphasized the continued immersion of the audience. This opera ends with Canio killing Nedda and her lover Silvio on the stage as the chorus surrounds him. The curtain comes down leaving this photogenic image.

© BAUS

The curtain rises up during the prelude of “Cavalleria” with final frame of “Pagliacci” still there. The whole cast stays still for some bars, but they start to salute and congratulate each other as Nedda and Silvio stand up and embrace Canio. The performers leave the stage after a good performance and the game continues.

After Turiddu’s off stage romanza, the chorus brought on dozens of the black square boxes which turn into dressing rooms, chairs and dozens of hangers with costumes. They begin dressing up for the new performance and putting on makeup. Mamma Lucia is a stage manager that at some point brings scores and librettos as the church chorus is sung in a rehearsal room with the director of the chorus making an appearance.

During the choir after the famous “intermezzo,” the members of the ensemble members take off their costumes and get back into their street clothes and take off the make up, indicating that they done with this day of work – Turiddu’s wine song is thus frame as a party after the performance. The tenor begins his final aria “Mamma, mamma! Quel vino è generoso” looking for his mother within the chorus, who is standing still, facing the back of the audience. Once he finds her, the chorus very slowly starts leaving the stage, with Turidduo following. Mamma Lucia and Santuzza remain, a large mirror facing them upstage. After the news of Turridu’s death and the agonizing high C, the two run off and the whole stage and theatre is illuminated, leaving the audience to face themselves in the large mirror. The effect was extraordinary and dramatic. The way Carsen links the two operas and takes the metaphor of theatre as a reflection of life to the maximum is impeccable.

The production is clearly created for this space as the amphitheatre shape of the auditorium facilitates the ability for performers to enter and exit through the aisles. The acoustics are splendid, permitting the chorus spread around the auditorium and the protagonists to sing with masks without noticeable interference.

© BAUS

A True Star

The row of Nedda is mostly written in the middle register of the voice with some high notes, there is not a constancy in the higher register, and it requires a voice that sound light. The soprano also needs to confront dramatic moments, like her duo with Tonio which is quite low and demands a strong low register. She also needs big resonant high notes that can express her desperation at the end of the opera when she is trying to remain in character. Soprano Ailyn Pérez, taking on the role for the first time, was a fantastic match for the role.

The American soprano has a truly lyrical voice, with a strong center and low register, but flawless and secure high notes with strong potency. She managed the most lyric moments with exquisite mezza voce and clean thrills, especially in her aria “Qual fiamma avea nel guardo!” In this famed passaged she delivered a perfect pianissimo A natural on the phrase “O che bel sole” and sustained fluid legato phrases that require several ascensions to high B flat during her duet with Silvio.

Pérez demonstrated desperation with a ringing high B natural at the conclusion of the work, as well as a solidly sustained line on “Ah! no, per mia madre” or in “al costo de la morte.” Pérez demonstrated that she could easily handle the challenges of this role by transforming from an idealistic youth full of love into a desperate person fighting for her life.

She also managed the physical demands of Carsen’s review splendidly while showing tremendous chemistry with her colleagues.

© BAUS

A Strange Fit

Brandon Jovanovich, played the role of Canio with determination and passion, but his timbre sounded strange as there is a big change between his middle and his high registers.

His voice sounds dark and round up until the high G, but when he goes higher the timbre becomes white and pale. Although he manages to keep great volume and projection, his high notes sounded artificial and sometimes insecure. He reached the high B natural “A ventitre ore” with no problems, but during latter parts of the work, when the tessitura rises to consistent high Gs and As, Jovanovich struggled.

“Recitar… Vesti la giubba” sounded labored with the high A sounding hoarse and unstable; he was out of fiatto and broke the legato line of the famous passage “Ridi, Pagliaccio, sul tuo amore in franto,” compensating with melodramatic effects which were acceptable at the Verismo school 70 years ago but feel a bit outdated today.

Fortunately, he rested up during the ensuing scene and sounded more secure and fresh when he returned. This final passage demands more high tessitura, reaching a high B flat with the line constantly forte. One might note that his vocal challenges were furthered by the physical demands of the production, including jumping off the stage and running through the aisles.

Tonio, the treacherous clown, was interpreted by Roman Burdenko. He did not sing the prologue in this production (as it is usually done) so the role wound up less demanding, especially since the challenges of this role are more dramatic than vocal. He has no arias, so he is always singing in duos or ensembles. The tessitura is quite central, except at the end of the opera when he has to sing a high G in a cadenza and several high Fs. Burdenko was very convincing as a singer and as an actor, with a very strong dark voice and an impressive charisma on stage.

Mattia Olivieri took the short role of Silvio, the lover of Nedda, which basically has a long duet and then a few short phrases. But this role requires a lyrical baritone able to portray a young lover, with long legato lyrical phrases and a high tessitura, keeping the voice above the staff with several high G flats and G naturals. With his sweet timbre, Oliveri demonstrated that neither the tessitura or legato phrases were a problem to him. He also convincingly portrayed the young lover, with him and Pérez igniting the stage during their sexually explicit duet.

Marco Ciaponi was impeccable in the even shorter role of Beppe, which has a short off-stage aria with a high G and A natural. He has a lyrical-leggero voice who could handle the tessitura of the aria easily.

© BAUS

Another Star Rises

Anita Rachvelishvili was the absolute protagonist of “Cavalleria Rusticana.”

There are good and bad singers, there are excellent singers, and then there are a just a few miracles of nature whose voice and stage presence is astonishing. Rachvelishvili is one of them and if she guides her career wisely, she will become a major part of opera’s history.

The mezzo’s round strong dark voice rings in your ears, and her presence hypnotize you, making it difficult to watch anyone else while she’s onstage. Her voice is potent in the middle and lower register. She keeps the timbre equal without needing to switch to chest resonance to make the low notes big. She’s just as impressive up top, maintaining the same timbre and volume. In essence, her voice is completely balanced from low to high.

Santuzza was written for a dramatic soprano, so the tessitura is quite high for a mezzo like Rachvelishvili. It is written constantly above the staff going to high A flat and high A natural constantly, which are notes that mezzo-sopranos must have; however, keeping the voice all the time around those notes is quite demanding. Moreover, Santuzza has several high B flats and an optional high B natural too.

Rachvelishvili had no problems with the soprano tessitura or with the high notes. The mezzo began controlling the torrent of her voice, singing in mezza voce during her dialogue with Mamma Lucia, and sustained it during the church scene all the way up to the last high B natural where you could hear her voice over the chorus and orchestra at their loudest. And this must have something to do with the staging too, as she began tormented but introverted and restrained.

It is in “Voi lo sappete, o mamma” where the character bursts out with passion and it was here that Rachvelishvili unleashed her sonorous voice with a powerful center and several thunderous high A naturals. But the tension kept growing during her duet with Turiddu, with the singing full of passion, regret and fury. After her duet with Alfio, with her intensity growing even greater, Rachvelishvili came back to the introverted remorseful girl, her voice lightening. Toward the end of the work she returned with a potent high B flat on “Oh! Madre mia” and before capping the night with a tremendous high C. It was the epitome of a spell-binding performance.

© BAUS

Powerful Figures

Brian Jagde performed the role of Turiddu. Having started his vocal training as a baritone, he posses a dark, round, beautiful voice, with potent high notes, ideal for the role. Overall, he was solid.

You could hear his glottis hitting the throat on some high notes and there was some patchy diction in some passages, especially with the pronunciation of the “T” and “R.”

Turiddu is a short role but the tessitura is quite high, which is uncomfortable for a dramatic tenor. Jagde’s off-stage opening aria “Oh Lola” featured a fluid vocal line, something not easy while going to high A flats constantly. He became really aggressive and assertive in his long duet with Santuzza, matching Rachvelshvili’s passion and making the passage among the most memorable of the evening. He had some trouble with the “wine aria” as the score demands a lighter tone and the conductor was likely taking a fast tempo, but he coronated the end with perfect high B natural. His last aria “Mamma, mamma, quel vino” was dramatic and moving with the tenor ending with on perfect high B flat. His incarnation of Turiddu was believable and powerful.

Gevorg Hakobyan had the chance to sing the prologue in I Paglliacci and then the role of Alfio which is even shorter than that of the tenor. The problem with “Pagliacci’s” prologue is the two high notes imposed by tradition: a high A flat on “di voi spiriamo l’aere” and the high G at the end of “Incominciate.” Otherwise the tessitura is affordable and the real task is coloring the phrases and communicating straight to the audience. Of course, singing this long aria, when you haven’t had the chance to warm the voice on stage is quite risky, but Hakobyan performance was impeccable. You could really see his communication with the audience as he colored every phrase. His high notes were flawless and robust.

Then he had a 90-minute break before interpreting the character of Alfio which is not quite as demanding as it does not go higher than G flat and is rather brief. Hakoyan proved himself a soldi actor and singer and gave an excellent performance.

Elena Zilio and Rihab Chaieb were irreproachable in their respective supporting roles of Mamma Lucia and Lola.

Also remarkable was the work of the chorus of the Dutch National Opera which sounded impeccable and then had to face a hard-physical work to fit the demands of the staging.

The orchestra of the theatre sounded irreproachable under the baton of Lorenzo Viotti, who made his house debut replacing the previously announced Sir Mark Elder. Viotti managed to retain tension and suspense during the dramatic moments, as well as lyricism during the intermezzos, reinforcing the beauty of the score. He chose faster tempi than usual for the section “Bada, Santuzza, Schiavo non sono” and Turiddu’s “wine aria,” but this suited the momentum quite well.

It was truly a splendid opening to the opera season for the Dutch National Opera, which sets the standard high for the rest of the year.