CD Review: Rosśa Crean & Aiden K. Feltkamp’s ‘The Priestess of Morphine’

An Fascinating Opera on Erotica and Morphine in the Third Reich

By Ona JarmalavičiūtėThe joined forces by librettist Aiden K. Feltkamp and composer Rosśa Crean brings the incredible story of Gertrud Günther (also known as Marie Madeleine) on a stage for the first time in the monodrama, called the “The Priestess of Morphine: The Lost Writings of Marie-Madeleine.”

Premiered on June 28, 2019, in the International Museum of Surgical Science, opera was soon recorded and presented as an album with the same title. Both creators of “The Priestess of Morphine” Feltkamp and Crean champion new classical music and opera, attempting in this form to communicate and be understood across the whole humanity. A beautiful portrait here brought into light is used as a vessel to openly see and discuss various topics, as much urgent now as back in the time of World War II – identity, drug abuse, and sexuality.

Meticulous Biography

The meticulous biography was based on the heroine, Marie-Madeleine’s collections of poems and prose narratives, telling the story of the young Jewish lesbian Gertrud Günther. Her erotic writings describe and remember a girl caught between her two selves during the Third Reich, who bravely sought her inner truth and passions while forced to live in the shadows. Born in 1881, in a middle-class Jewish family, Gertrud Günther aka Marie-Madeleine aka Baronness Von Puttkamer grew up to be a poet and novelist. Starting to write at the age of fifteen, she wrote over forty-six books, thus establishing a name for herself as a writer of lyrical, sensual, erotic, and passionate poetry and prose.

No wonder her bestselling books of the early twentieth-century were deemed as shocking and sensational, as they openly dealt with the author’s eroticism and love for morphine. Even “Auf Kypros” – her first book of poetry under the pen-name Marie-Madeleine, which was published at the age of nineteen (1900), was a collection of lesbian-themed erotic verses. At the time her work was seen as pornographic – contra to societal standards of morality.

Although her poetry reveals her as a lesbian, Marie-Madeleine had married a man from the Pomeranian nobility who was thirty-five years her senior – Baron Heinrich Georg Ludwig von Puttkamer – and moved into a villa in Grunewald, Germany, where she became a socialite and began using morphine recreationally. By 1910, her writings were not only centered on lesbian erotic love but also on the use of morphine. It comes as no surprise that her husband’s death in 1914 led to her morphine addiction. “No more seeing, no hearing, no feeling! — I want to tumble into the night, into the dark night,” writes Marie-Madeleine at that time, lamenting her husband’s death and praising morphine as her reprieve from agony.

She enjoyed immense popularity throughout her life and her books were published in the thousands (“Auf Kypros” sold over one million copies during her lifetime). That is until the year 1932 when Nazis condemned her work as degenerate and most of her books were destroyed. Despite the obvious threat to her personal safety, Gertrud Günther continued writing in defiance of the Nazi mores. In 1943, she entered a sanatorium for morphine addiction where she died a mysterious death while under the care of Nazi doctors only a year later.

Brimming with Emotion

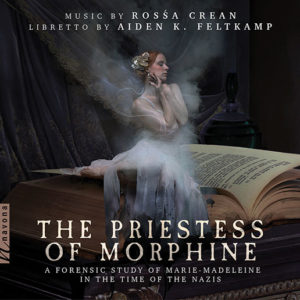

The poems and prose presented in ‘Priestess of Morphine’ brim with eroticism, intoxication, desire, pain, jealousy, loneliness, and passion. Many of them were translated for the first time into English by the librettist Aiden K. Feltkamp. The cover illustration (Eugène Grasset’s The Morphine Addict (1896) depicts a young woman injecting herself with a needle of morphine.

The monodrama’s unusual story is parted into three main sections that reflect the time period before, during, and beyond Marie-Madeleine’s addiction to morphine. The first period “Opus with Erotica” includes poems from “Auf Kypros;” the second one “Opus with Morphium,” includes novellas and poems from the collection “Taumel” and “Requiem for a Modern Poet,” commemorate both her own poems and a number of poems and images by others.

Together with the intriguing structure of the monodrama, the ensemble is the most unique. Silence filled with tension and anticipation is pretty much the main creative tool for this piece. On stage, sopranos Jessie Lyons and Katherine Bruton represent each side of Gertrud’s life—one mature and narrative, the other youthful and poetic. Unusual instruments, such as the vibraphone and the waterphone, weave unexpected textures and moods with violin and cello floating between traditional and percussive styles, lulling the audience into a sensual, dreamlike state.

This powerful and perceptive opera is the most comfortable way to explore the young woman’s suffocating trauma, by situating Marie-Madeleine’s work in the historical and artistic consciousness of the time with an eye towards healing. The new opera and recording make Marie-Madeleine a rediscovered heroine of lesbian and drug literature.