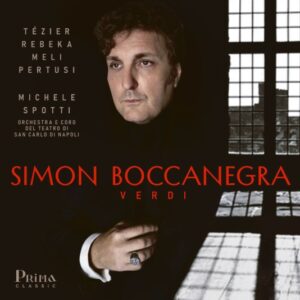

CD Review: Prima Classic’s ‘Simon Boccanegra’

By Bob DieschburgRarely has a single performance so cornered the discographic record of an opera as Claudio Abbado’s “Simon Boccanegra” from 1977. And my use of the possessive is, in this case, far from aleatory: Abbado lays claim to the score with an authority scarcely less than Verdi’s own—or would Hugo Shirley otherwise have spoken in superlatives so unsparingly when Gramophone revisited the DG classic in 2018?

What, then, is to be expected of a new release, and especially Prima Classic’s latest publication, headed—like its predecessor—by a cast of illustriously voiced superstars? In short, its merits are to be found in the sum of its parts rather than in an architectural whole.

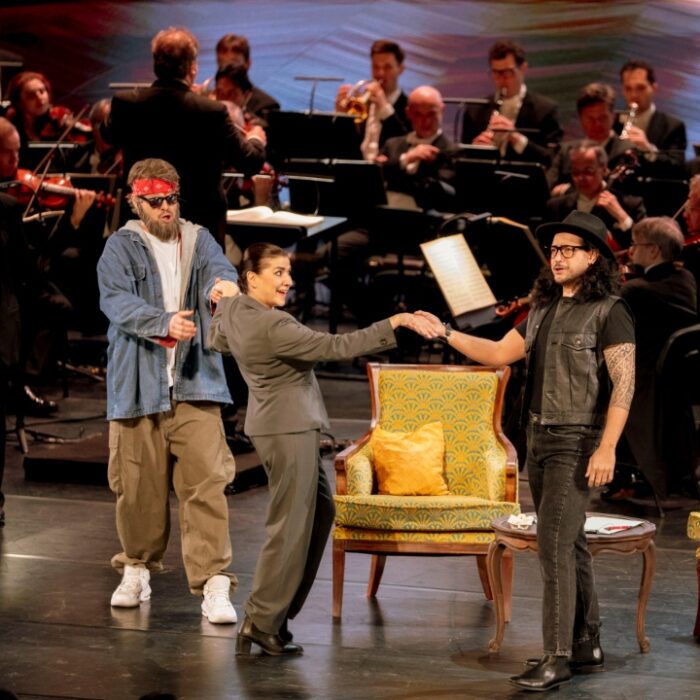

The Neapolitan orchestra, under Michele Spotti, is dramatically edged (the performance was recorded live), though its rather crisp tempi do not always work in favor of atmospheric color. For instance, the Italian maestro does not emulate Abbado’s insistence on the nocturnal (think of the Prologue), nor do his strings quiver with the kind of restrained secrecy that more generously deployed tempi might have suggested.

Instead, the orchestra sounds rather lean, almost chamber-like, in clear support of the voices, which—like Marina Rebeka’s—unfold with staggering immediacy. The Latvian soprano molds the line into a continuous ebb and flow; she excels in dynamic control (mezzo-pianos and pianos abound), while a lingering impetuousness aligns her interpretation with the dramatic verve of “Norma” (released on Prima Classic in 2024).

There are, for instance, limited traces of Mirella Freni’s sweetness in “Come in quest’ora bruna.” Yet Rebeka asserts herself with poise, projecting a theatrical presence that arguably lifts the role of Amelia out of its inwardness—toward a propulsive force within the narrative.

Francesco Meli as Gabriele Adorno is rather serviceable, though I find his interpretation a tad shallow, if not one-dimensional. And while Adorno, psychologically, is meant to be little more than an overexcited youth, one cannot help but feel that the character is underplayed. Still, as a major Verdian interpreter, Meli phrases his Act one “Sento avvampar nell’anima” with considerable routine, in the ominous middle ground between mid-century legato and proto-veristic declamation—though the acuti remain somewhat harsh.

An “acting voice” (in Walter Legge’s sense), Michele Pertusi portrays the torment of Fiesco with chiaroscural precision. It does not best the regal boom of, say, Nicolai Ghiaurov, nor does it exhibit the cavernous blackness of Boris Christoff or Martti Talvela; yet the dynamic refinement of Pertusi’s “Il lacerato spirito” conveys a tortured humanity, grounded yet devoid of pedestrianism.

But what of the title character? Ludovic Tézier gives a lesson in grandiloquence, in line with his portrayal of Rodrigo in Verdi’s “Don Carlo.” Throughout the opera, the breadth of his phrasing imparts a nearly unmatched nobility to the Doge. His dying monologue (“Gran Dio!”) rings like a dignified farewell, shaded with mezzo-pianos and an aptly scaled sense of pathos. In the recognition duet with Rebeka, he similarly evokes paternal tenderness through a relative simplicity of means. Stitching together the recitativo passages of “Figlia! A tal nome io palpito,” he conveys emotional integrity without mannerism, relying entirely on vocal technique.

Spotti’s clear, supportive approach works wonderfully in the duet’s intimacy, whereas it does not quite do justice to the agitation of the Council Chamber scene. I have always understood its superb blend of harmonic fragmentation and Boccanegra’s subsequent declamatory entrance as a psychographic representation of two states in collision.

Yet while Tézier’s “Plebe! Patrizi! Popolo!” seamlessly oscillates between declamation and legato-inflected elegance, the orchestra does not entirely follow suit. It behaves too functionally for my taste (especially when measured against the DG benchmark), and thereby illustrates the coexistence, in this “Boccanegra,” of musical brilliance and high-level execution. Prima Classic offers a 21st-century milestone—even if, in absolute terms, I would still opt for the 1977 reference.