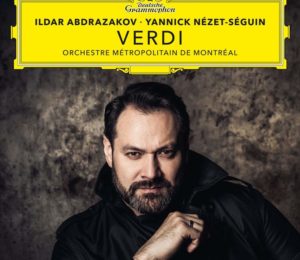

CD Review: Ildar Abdrazakov’s ‘Verdi’

Ildar Abdrazakov Manages Some Vocal Spectacle Despite Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s Overemphatic Interpretation

By Bob DieschburgSince his breakthrough as Rodolfo in Bellini’s “La Sonnambula,” 42-year-old Ildar Abdrazakov has cemented his reputation as one of the world’s leading bass singers at both European and American opera houses.

With his repertoire spanning the early and mid-19th century, he has gradually moved from the Belcanto tradition to Verdi and the development of modern music drama per se; it is not surprising then that he uses his powerful voice to pay tribute to the great composer by incarnating some of his most fascinating creations. “Verdi” marks the bass’ solo debut with the Deutsche Grammophon and it turns out to be a solid and sometimes monolithic compendium of warriors, prophets, and intriguers.

No Chronology

A first glance at the track list reveals that the arias do not follow any chronology. The recital starts with the showpieces from “Attila (1846)” which Abdrazakov has performed at last year’s opening of La Scala in Milan. They are followed by the great monologue from “Don Carlo (1867/84)” and Zaccaria’s solemn admonitions from “Nabucco (1842).”

The same holds true for the rest of the album which pursues its anachronistic zigzag only to conclude with “Ernani (1842).” The track arrangement hardly reveals an underlying scheme and as much as it points to an overly hasty execution, the missed chance of providing a chronology and tracing the composer’s development is a bit of a letdown.

It should after all be reminded that Abdrazakov knows about the philological intricacies and stylistic progress of Verdi’s operas through his work with chief conductor Riccardo Chailly at La Scala. The latter is mounting a large-scale Verdi cycle that the Russian-born singer has been involved with and the idea of establishing a dramatic teleology cannot have escaped him.

For instance, the juxtaposition of “Attila” and “Macbeth” would have been an easy example to illustrate this; the so-called tinta in the score of “Attila” is a foreshadowing of “Macbeth” and a comparison between the arias “Mentre gonfiarsi l’anima” and “Come dal ciel precipita” would have been a revealing experiment.

Vocal Emphasis

Instead, the focus lies entirely on Abdrazakov’s voice which defies the traditional categories of basso cantante and basso profondo. His vocal character can indeed be described as eclectic – and this polyvalence marks both his strengths and weaknesses.

A good example is provided by Attila’s cabaletta “Oltre quel limite.” While the voice is lacking the agility of Samuel Ramey and betraying uneasiness on the melisma of “spe-etro,” Abdrazakov nonetheless manages to endow his interpretation with a degree of gravitas that a lyric bass could not achieve.

Compared to previous recordings the voice has gained in texture, displaying a tonal maturity that particularly suits the interpretations of Jacopo Fiesco and Philip II. Drama is expressed at its finest in the Spanish ruler’s monologue. In “Ella giammai m’amo,” the legato gains an intensely descriptive quality that contributes to the sharpening of Philip’s psychological profile.

Equally remarkable is the intelligent use of the mezza voce which – in Procida’s arioso (“O patria”) – is reminiscent of the Golden Age of operatic singing.

The same holds true for his rendering of “Come dal ciel precipita.” By covering his vowels through the so-called emissione coperta, Abdrazakov is conjuring an iconography of terror that fittingly echoes Banquo’s state of mind. Even his characteristic and sometimes oversized vibrato is less an indication of technical deficiencies than the pretext for increased expressiveness. The result is a convincing series of portrayals that benefit from the bass’ on-stage experience.

With the exception of “Nabucco,” Abdrazakov has sung the roles of Verdi in stage productions all over the world.

The only significant flaw, however, is his inclination to sing high notes on a climactic forte; by opening the vowels he is losing focus. Most strikingly, this happens in the arias of “Oberto,” “Macbeth,” and “I Vespri Siciliani.” While there is no stylistic legitimation for such an emissione aperta, it remains a rather curious trait that is not unlike Pavarotti’s late mannerisms and his attempts to achieve expressiveness by widening the sound of top notes.

Lacking In Verdian Vision

Lastly, it is worth addressing the Canadian Orchestre Métropolitain. Under the baton of Yannick Nézet-Séguin, it adopts an almost symphonic approach that misreads the early scores by blatantly overemphasizing the weight of the orchestra. Instead of supporting the vocal line, it presents the listener with a cinematic sound panorama that luckily doesn’t submerge Abdrazakov’s voice. Only in the elegiac passages from Don Carlo do the strings unfold their dramatic qualities as indicated in the score.

While it is safe to assume that the orchestra isn’t familiar with the early to mid-19th century repertoire, the same can be said about Nézet-Séguin. The artistic director of the New York Metropolitan Opera has demonstrated his universalist ambitions by tackling very heterogeneous pieces – both on-stage and in the recording studio. However, his interpretation of what is essentially the emancipation from the Belcanto-tradition is generally overdramatic and, in some cases, erratic.

This holds especially true for the opening tracks of the album. Thus, the da capo is slowing down after the rushed beginning of Attila’s “Oltre quel limite.” This imbalance between the first and the second half of an otherwise exciting cabaletta doesn’t make sense at all. The so-called stretta would indeed suggest the exact opposite – that, for the sake of dramatic tension, the speed increases. Here, the tension is unfortunately lost.

What remains is the overall strong performance of Ildar Abdrazakov whose multifaceted voice is conjuring terror, awe, and solemnity at will. “Verdi” thus remains a vocal spectacle more than a quest for stylistic authenticity.