Massenet’s opera “Thaïs,” set in 4th century Alexandria, focuses on two individuals with diametrically opposed outlooks and lifestyles. There is the hedonistic courtesan Thaïs, who seeks only love—although for no longer than a week at a time—and there is a cenobite monk named Athanaël, an ascetic, whose aim is to turn the courtesan to the path of righteousness. While he does ultimately succeed in this task, he is ensnared by Thaïs’ beauty, betrays his faith, and succumbs to the passions of the flesh.

Following its dismal premiere at the Paris Opéra in 1894, now remembered almost solely for the fact that the prima donna Sybil Sanderson ‘accidentally’ exposed her breast on stage, Massenet undertook a substantial revision of the piece. Out went the original ballet and act two musical interlude, replaced by a new seven-part ballet and the introduction of the Oasis scene (act three, scene one), which forms the work’s emotional and dramatic climax. Although it again flopped on the new opening night, it eventually met with success, securing almost 700 performances alone at the Palais Garnier before being withdrawn from its repertoire in 1956. However, while it still manages to maintain a foothold in the repertoire of many opera companies across the world, it is clearly situated in the shadows of Massenet’s more successful “Manon” and “Werther.”

Why this should be the case is somewhat of a mystery, for “Thaïs” is a dramatic work with an engaging and imaginative score, if occasionally a little brash, offering plenty to delight the ear and the eye. The roles of Thaïs and Athanaël are convincingly drawn, offering the soprano and baritone substantial challenges. There is dance, local color, pleasing choral episodes, and delightful musical interludes. The libretto eschews a philosophical discussion about the moral rights and wrongs of the protagonists’ behavior, and instead focuses on their emotional journeys, something perfectly suited to our modern outlook. What is even more perplexing is that even the marvelous Decca benchmark recording, luxuriously cast with Renée Fleming and Thomas Hampson, failed to lift it from its current neglected position.

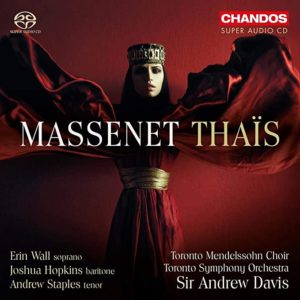

Chandos’ new recording of “Thaïs” now adds further weight to the argument that the opera deserves greater consideration. Leading the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and a cast which includes soprano Erin Wall in the title role and baritone Joshua Hopkins as Athanaël, Sir Andrew Davis produces a reading very different from the Decca set. The act two ballet has been cut to a single part, which is understandable given that this recording is based on a concert performance. From a dramatic, if not musical, perspective, this edited version seems better suited to a CD format. While the Decca recording tilts more towards the beauty of Massenet’s score, the Chandos set is more squarely focused on developing characterization and uncovering the emotional depths of the protagonists.

Two Solid Leads

Wall’s Thaïs is an earthy and seductive portrayal in which her sexuality and worldly-wise nature in the first half of the opera are clearly wrought, which successfully highlights her spiritual transformation, and propels the opera towards its conclusion. Her aria, “Qui te fait si sévère et pourquoi démnes-tu la,” on her first meeting with Athanaël is delivered with playful irony and seductive charm. Her voice flutters and dances gently, but with enough of an underlying edge to signify her worldly nature. How different she sounds in her later aria, “O massager de Dieu.” After having repented of her sinful life, she thanks Athanaël for all he has done, her voice now open, honest, and calm, without the earlier deceptive playfulness. Throughout, Wall uses the flexibility of her voice to inflect the vocal line with meaningful emphases, changing colors and dynamics to flesh out her emotions. She uses this vocal skill to good effect in the mirror aria “Ô mon miroir fidèle, rassure-moi,” in which her pleasing timbre and fine legato convey the emotional weight of the piece.

However, Wall sometimes loses her vocal beauty and she does not have the facility for nuance and delicacy that other past interpreters produced. Moreover, there is an unevenness in her delivery. Occasionally in the more extreme passages, the voice lacks the necessary support and the vocal line wavers a little. Nevertheless, it does little to detract from the overall portrayal. Rather, it presents us with a different emotional perspective, one which is equally dramatically convincing and, despite the vocal unevenness, pleasing on the ear.

Likewise, Hopkins also sacrifices a degree of beauty in order to deepen the characterization. He does not compromise in his presentation of Athanaël as a self-deluded, intolerant egoist, whose presence is always uncomfortable and humorless. There is little in his portrayal with which one can sympathize. His first words upon meeting Thaïs, “Contempt for the flesh, love of pain, austere penance,” paint a perfect picture of his character. His aria, “Voilà donc la terrible cité!” is sung with fierce emotion, as he rages against the sins he hates so much. Enveloping the vocal line with a strident uncompromising veneer, Hopkins skillfully places accents and dynamic inflections to create a well-crafted picture of a religious zealot. In the opening lines of the aria, however, Hopkins successfully highlights Athanaël’s hypocrisy as he sings almost with pride of the “terrible” city of Alexandria, the city of his birth, the city of sin. Athanaël’s one act of genuine sympathy comes as he cleans Thaïs’ bleeding feet, which precipitates the central duet, “Baigne d’eau mes mains et mes lévres.” His voice blends sympathetically with an exhausted Thaïs and, for the only time in the opera, he exhibits kindness towards another human being. Even as Thaïs lies dying, one cannot help but think that he is grieving for himself. It is an excellent performance, one that gets to the heart of the character.

The pivotal exchanges between Wall and Hopkins are successfully rendered with an intensity which enabled their changing relationship to be clearly defined, and the dramatic thrust of the narrative to be maintained. At every stage, both capture their characters’ emotional complexities. As he drives Thaïs through the desert Athanaël’s self-hatred and delusion are all too clear as he sings with uncompromising menace in his voice, forcing her onwards, and dissatisfied with her genuine repentance, he wants her to suffer. The final scene ends with the duet “Te souvient-il du luminueux voyage…,” Thaïs in a state of rapture prepares to meet her god, while Athanaël is confessing his love for her and renouncing his god. Although calm at first, Wall’s voice, coated with increasing ecstasy, rises strongly and shines brightly in an emotionally charged climax. It is not perfect, the top notes are not delivered securely, but this adds to the emotional frisson of the scene, and the emotional energy is palpable. Wall’s emotional identification with Thaïs is gripping. Meanwhile, Hopkins without shrinking into the background, wallows in his own grief, his voice supporting Wall’s ecstatic death, bringing the opera to a satisfying conclusion.

Impressive Support

Other members of the cast all produce solid performances in the supporting roles. Andrew Staples is excellent as Nicias. He has an attractive, securely seated tenor, which he used well to develop the young, but worldly-wise philosopher.

Nathan Berg is a suitably authoritative Palémon. His deliberate phrasing, underscored by his resonant bass nicely captures the character’s wisdom.

Soprano Liv Redpath and mezzo Andrea Ludwig bring the necessary humor to the roles of Corbyle and Myrtale. Along with Nicias, the flirtatious pair create an erotically-charged scene in which they recloth Athanaël, much to his annoyance. But like any hypocrite, his complaints are too strongly presented.

The mezzo Emilia Boteva made a suitable abbess Albine, although has possibly too much vibrato for some tastes.

The real star of the performance, however, must be Sir Andrew Davis and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra who have created a reading which is not only dramatically nuanced but also brings out the exquisite beauty of the score. The score’s textures are fully explored, and the interplay between the sound of the full orchestra and the almost chamber-like and solo sections are wonderfully contrasted. Davis judges the pace to almost to perfection, applying the necessary dynamic emphases with a keen eye to the dramatic effect.

Whilst this new Chandos recording does not displace the older and aforementioned Decca recording, it is certainly a worthwhile addition to the catalog.