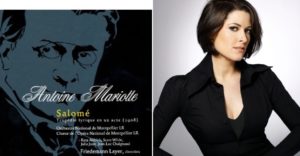

CD Review: Antoine Mariotte’s ‘Salomé’

Kate Aldrich Shines in Recording of Elusive Opera

By Bob DieschburgOn its west facade Rouen Cathedral features a bas-relief of Salome dancing on her hands for the Tetrarch and his guests. In a luring form of “danse macabre,” she thus seals the fate of the Baptist whose execution is shown in the following scene.

Flaubert is said to have derived inspiration for his recounting of the Biblical story in the Rouen sculptures – and indeed the description of Salome “like a giant beetle” can easily be transferred to the twisted movements of the Medieval artwork. More importantly, Flaubert’s “Hérodias” became the literary prototype of a whole series of adaptations ranging from Oscar Wilde to Massenet and Strauss. The latter’s “Salome” has established itself as the definitive version on the opera stage.

However, it led to the unjust neglect of a hidden gem: Antoine Mariotte’s “Salomé” which has been sporadically revived at the Prinzregententheater and the Wexford Festival in 2014. The present recording – captured at a 2005 live performance in Montpellier – is to my knowledge the only physical copy available and with Kate Aldrich in the title role deserves every attention.

The Elusive Antoine Mariotte

The life of Antoine Mariotte (1875-1944) is eclectic in every sense of the word. The uncertainty of his vocation – torn between a naval career and his debut as a composer – marked the very beginnings of his artistic output; prose and verse alternating with an occasional painting and the more substantial outline of operas including “Esmeralda,” a piece on prehistoric Brittany, and “Salomé”.

His affinity with the princess of Judea came from Wilde’s eponymous play which Mariotte read during his voyages in the China Seas. Yet “Salomé” only premiered at the Grand-Théâtre de Lyon in 1908 – that is three years after Richard Strauss’ “Salome” was produced in Dresden. The rivalry with Strauss, exacerbated by a nationalistic discourse along the lines of the 1870 victory of the “Reich,” can also be held accountable for the French “Salomé’s” neglect in the international repertoire.

Indeed, Mariotte believed to have the estate’s permission to use Wilde’s text; the rights, however, laid with the Berlin publisher Adolf Fürstner. The latter represented Strauss and imposed humiliating conditions on the performance of the new opera.

For instance, 40 percent of royalties Mariotte would have to pay to the German maestro and an extra 10 percent to Fürstner himself. At the end of the season, the stipulation read, the scores needed to be destroyed. It is through the intervention of Romain Rolland that the piece was emancipated.

The composer – a pupil of Vincent d’Indy – continued writing for the stage, although neither “Le Vieux Roi” (1911) nor “Esther, Princesse d’Israel” (1925) or the later “Gargantua” (1935) had much of a posterity. Part of the reason might have been Mariotte’s relative absence from Paris and its musical scene; apart from a three-year interlude serving as director of the Opéra-Comique his naval, teaching, and composing activities were taking place outside the capital.

The French Salomé: “Like a Giant Beetle”

It would be futile to measure the French “Salomé” against the merits of its German pendant; too big are the differences in orchestral texture, chromaticism, and general sentiment. The narrative also focuses less on the sexualized princess and the onset of madness than on a social cluster of transgression.

Thus, room is given to the recounting of the murder of the Tetrarch’s brother-in-law. Similarly, the young Syrian’s role is greatly expanded and the repeated mention of the title character adds to her mysteriousness before she appears in Scene II.

Maybe the greatest asset of the opera lies in the libretto; making only minor changes to its structural and poetic cohesion, Mariotte retains the musical flow of Wilde’s tragedy and one cannot help but reiterate the judgement of Alfred Lord Douglas: “It seems that, in reading, one in fact hears it; but what one listens to is not the author, it is not the unfolding of a plot, it is the song of various instruments.”

With its innate musicality, the play lends itself to a dramatically effective scoring and Mariotte adopts a traditional, yet simple organization into seven scenes to recreate its progression towards the supreme kiss and act of necrophilia. His musical jargon is rooted in the sophisticated harmonies of Debussy and despite its epigonal inspiration retains a great deal of melodic interest, such as in the evocation of the moon. Certainly the way is paved for harmonic experiments in the vein of Puccini’s “Turandot.”

The blend of themes is equally noteworthy and one remains baffled by the gentle transition of the lunar theme into the introduction of Salome stepping out on the balcony. While there has been speculation about the paronomasic relationship between the names Salome and Selene – goddess of the moon – it takes the intelligence of Mariotte to link them through thematic entities.

His most impressive device, however, pertains to the underscoring of the kiss with a humming choir. Taking the action not to the ecstatic heights of Strauss, but having them sink into some otherworldly eeriness makes for a spectacular conclusion that gives the mezzo soprano ample opportunity to display her acting skills.

Aldrich Taking the Lead in Montpellier

The Montpellier recording counts, among its many assets, the assured conducting of Friedemann Layer, a veteran of the fin-de-siècle repertoire and former assistant to Herbert von Karajan. One cherishes his rather symphonic take on a score that impresses through its variety of nuances rather than sheer volume.

At his disposal is a very homogeneous cast that is led by the bass of Scott Wilde and Kate Aldrich’s sumptuous mezzo-soprano. Striking the balance between vulnerability and the eruption of amorous craze, she is an ideal cast for this undeservedly forgotten opera.

On musical grounds “Salomé” can easily assert its place among its more prominent contestants and, short of the final spark of genius, it nonetheless allows for a grappling listening experience – if only for the awe-inspiring finale.