Opéra de Paris 2022-23 Review: Nixon in China

Technical and conceptual adjustments could smooth out the show

By João Marcos CopertinoPerforming “Nixon in China” nowadays is a particularly hard task: in Paris, mountains of burning trash compete with the buildings; In the United States, a series of attacks on the arts and on intellectual freedom headlines newspapers; And most importantly, war is happening not so far away from France.

John Adams and Alice Goodman’s “Nixon in China” addresses today’s realities as much as those of the end of the Cold War. We are, again, divided by extremes. Paris Opera’s first-ever staging of “Nixon in China,” directed by Valentina Carrasco, virulently condemns the abuses of authoritarianism, but more than once— scenically and musically—seems to miss the mark.

Carrasco’s Staging Original

It is hard to detach “Nixon in China” from the staging—and the persona—of Peter Sellars. He is, somehow, the mentor of the opera, and his original staging—and all the subsequent ones—are still impregnated by his presence for anyone who even vaguely knows the opera.

Carrasco managed to propose something original. “Nixon in China” may be an increasingly popular opera, but it is still in the process of becoming cemented as a part of the standard repertoire in Paris. To my knowledge, there have only been two different productions of the opera in the city since its premiere in 1992.

Carrasco wittingly plays with grandiloquence and symbolism. Carles Berga and Peter Van Praet’s scenarios allude to an amicable ping-pong game in 1971 and the famous “ping-pong diplomacy” between USA and China in the following years.

Ping Pong is a particularly elegant sport: its competitive rallies can give rise to apparent cooperation, as the rapid swinging of rackets and flying of little balls gives the impression, all the greater for its compact field, of a dance. The rackets need to hit the balls with precision and modulated strength; otherwise, the game does not flow. Carrasco uses this graciousness of the sport wisely. The ping pong balls can be symbols of China’s violence but also snowballs during Pat Nixon’s alienated and alienating wanderings through Beijing.

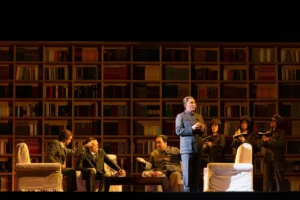

Other symbols are used on the stage with some complexity. A charming Dragon dummy with a soul of a frisky retriever represents China. America (and Nixon’s airplane) is an ominous silver eagle with luminous eyes. Carrasco, however, leaves little space for ambiguity about China’s undemocratic regime. The second scene of the first Act depicts, in the basement of Mao’s library, on-stage torture and the burning of forbidden books.

The explicit depiction of the regime’s brutality gives the lie to the seeming cordiality of a Mao who welcomes “right-wingers.” A special homage, on video, to the persecuted western music artists humiliated by the regime fills the gap between the second and third Acts.

The main issue with Carrasco’s staging is that it is sometimes hard to tell whether her criticism was directed toward Maoist China’s authoritarianism or, on the contrary, toward the Chinese people. Her decision to de-sexualize and emasculate Mao—a maneuver not super evident in the score—could be seen as a revival of such classical forms of criticism as Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator.”

However, some things were, to say the least, pathetic and flirted with many stereotypes of East Asian racist representation. The construction of a caricature of Chiang-Ch’ing followed the emasculation of Mao. She is overly controlling, teaching her helpless husband how to play ping pong—even though she is bad at it. Madame Mao (also, only for Carrasco) does not know how to operate a portable radio, needing Henry Kissinger’s help to make it work (she did not know it had an antenna…)

In the third Act, Chiang-Ch’ing is carnalized. Carrasco transforms Peter Sellars’ representation of sexual abuse committed by Mao into a scene of quasi-intimacy between a sexually charged couple that, somehow, shares affection.

More than the same misuses of tropes unrelated to racist practices of representation, Carrasco’s staging fails to elevate “Nixon in China” to a more truly relevant political debate. “Nixon’s” original premise is almost hard to believe.

Once upon a time, two of the most problematic figures of the last century—an autocrat who commanded a sanguinolent revolution and an [almost] impeached and humiliated right-wing president—started a diplomatic relationship that changed how politics could function in the middle of a not-so-Cold War.

Goodman’s libretto is not, by any means, forgiving of these political figures, but it manages to invite us to approach them as humans. To make caricatures of these human beings denies opera its power to bring together politics and individual tragedy. In “Nixon in China,” we are invited to understand the perspective of even those who wronged us, and, at least during the first two Acts, I could not see that in Carrasco’s staging.

In her strong take against Mao and Maoist China, Carrasco reveals a political shallowness foreign to Adams’ score. While Mao’s violence is made pornographically evident, Nixon’s wrongdoing, when it appears, is punctual, projected, and spectral. Quite likely, the deepest—and most politically compelling—moment of the staging was completely detached from Adams’ score.

As an entr’acte between the second and the third Act, Carrasco showed a fragment of Isaac Stern’s 1981 documentary “From Mao to Mozart,” with a powerful account of the torture and public humiliation of Western music teachers by Mao’s regime. It is a very strong denunciation of the violence of the Cultural Revolution and conveys facts that are important to be known. But it is neither in Adams’ score nor in Goodman’s libretto. It seemed redundant after the unambiguously critical take on Maoism in Chiang-Ch’ing’s second Act, ‘I am the wife of Mao Tse-Tung.’

Nevertheless, Valentina Carrasco’s staging is a very strong visual experience, and most of its representational problems would not be hard to fix with a few changes in the stage directions. The public seemed to enjoy the spectacle. Still, it offered little insight into this political moment, in which Paris—and the Western world—is perhaps as badly in need of a political bridge as they were when Nixon went to China.

Problematic Microphones

A small note on microphones is necessary when talking about Adams’ music. Although they always produce controversy when used in an opera production, Adams insists on using microphones, and Carrasco stuck to the composer’s requirement. The amplification, directed by Mark Grey—a specialist in Adams’ music—does not necessarily enhance their voices to levels that make them audible.

In Carrasco’s Paris production, as in the 2011 production at the Met Opera, the amplification leads the audience to continually question where the sound is coming from. This uncertainty is not new to an operagoer, but in “Nixon in China,” the ambiguity and sense of suspicion are heightened by the microphones, which, given the opera’s political context, is perhaps unwelcome.

It is tough to assess this performance musically because it was almost impossible to hear most of the singers during the first Act. Although the singers were microphoned and I was just a few yards from the stage, the voices were almost inaudible. I do not know if this was due to the many merits of Opera Bastille’s failed acoustics or to Dudamel’s massively loud orchestra, but it was very disappointing.

Individual Performances

Thomas Hampson’s ‘News, News, News’ seemed to be well performed scenically—but only vocally, no more than fragments of a voice sometimes crossed the orchestral barrier. This is not, by any means, a comment on the singers’ vocal capacities—everyone who has ever heard Renée Fleming or Hampson is well aware of their musical and vocal powers. If anything, this might be the most stellar cast ever to sing “Nixon in China,” which would be more than evident if some of the technical problems were fixed. But in a production with microphones, even in a fairly big opera house (2,700 seats, approximately), hearing the singers should not be a problem. It is another problem that is easy to fix.

In the second Act, however, the singing was more audible—but not entirely. Renée Fleming’s Pat Nixon was great. In her debut singing the role, it seems that the soprano’s extensive experience singing Mozart was well-suited to the construction of a character who is both sublime and a bit naïve, if not pathetic—despite her working-class roots.

Fleming’s “This is prophetic” found a genuine warmth, even in its evocations of the most dated forms of the American Dream. Fleming is particularly good at creating phrases that bring a sense of heroism to the banalest daydreams and fill Goodman’s words with meaning; after all, “why regret life which is so much like a dream?” When Fleming sings of the returning soldier, ‘Let him be recognized at home,’ Pat Nixon’s daydreams were a welcoming utopia.

Thomas Hampson’s Nixon, sporting the most unforgiving of all wigs, was charismatic and intentionally opaque in the upper register. However, his Nixon is a bit more pitiful and less tragic than in historical opera. It is, nevertheless, evident that Hampson is quite well-acquainted with Adams’s writing. In this third act scene (‘this is my way of saying thanks’), his “thanks” on a high G sounded almost like a “quack,” an active decision that makes Nixon almost likable but not heroic.

John Matthew Myers’ Mao showed a great command of Adams’ lyrical approach to politics. His voice has a particularly good and heroic upper register, with a tenor timbre that sometimes sounds more baritone. His expressivity connects Mao to characters like Peter Grimes—a link that I would not expect otherwise. He gave a sense of vocal dignity to a character the staging mocked most of the time.

Kathleen Kim, scenically, was a caricature of a political figure, but vocally she was a resort of lyricality. Her first aria—the opera’s subliminally nauseating highlight, ‘I am the wife of Mao Tse-Tung’—was the dramatic gravitational point of the night. Her high notes were sonorous and focused, with precise intonation. It is clear that she is extremely well-acquainted with the role.

‘I am the wife’ has attracted more than a few coloratura sopranos. Its catchiness, combined with its great technical and musical demands and with the charismatic depiction of someone all but mindlessly in the grips of political fanaticism, certainly marvels anyone from the first hearing. When Peter Sellars repeatedly compared Adams’s music to Mozart’s, he probably had in mind the way this instrumentalization of the voice for the depiction of corrupt politics still manages to amaze the audience with great singing.

In a certain way, ‘I am the wife’ is not so far from “Der Hölle Rache,” and the repeated ‘Joy’ is sung by the chorus in the back with perhaps less irony than one might think. Despite the evident depiction of authoritarianism, we, the audience, feel great joy hearing such an aria, especially when Kim sings all the high notes in tune. She embraced a leggera sonority that makes everything simultaneously impressive and macabre. It was even more joyful to hear Kim singing the melancholic melisma of Chiang-Ch’ing in the third Act. Her capacity to sing along with the violin solos creates a welcoming atmosphere of reflection.

Xiaomeng Zhang’s Chou En-Lai was extremely precise. The singer was commanding, making Chou En-Lai more of a protagonist than is usually granted to the role. He seemed to have given the prime minister the sonority of Verdi’s historical operas; his voice sounded well even in the technical fiasco of the first Act!

The loudest voice of the night, regardless of amplification, was Joshua Bloom’s. Henry Kissinger is quite likely the opera’s most problematic figure, and the singer did not refrain from a matching vocal tone. His ‘so hot,’ as he views the play’s depiction of an attack on a young peasant, showcases the same flawed vocalization that we heard repeated in Nixon’s thanks.

Yajie Zhang, Ning Liang, and Emanuela Pascu correctly sang the trio of Mao secretaries. The chorus, prepared by Ching-Lien Wu, sang well, though their French accent was noticeable when singing in English.

The Opèra de Paris Orchestra, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, had great moments, especially in the third Act. Adams’ score requires great rhythmic precision that Dudamel mastered almost all night. However, it is undeniable that, again, it played unnecessarily loud during a great part of the night. It might have been the fault of the amplification, but the loudness did not improve the music.

The Kinks Need Working Out

With what is quite likely the best possible cast possible for “Nixon in China” in Paris, Carrasco’s staging and Dudamel’s musical direction are both extremely promising, but, to make the opera work properly, some technical and conceptual adjustments are needed. Nevertheless, the most important aspect was achieved: John Adams’ music was certainly a hit.

Adams, who was present at the premiere, received an unequivocal standing ovation—something unusual at Opéra de Paris. It was almost certainly not the performance itself that they were lauded, but the magnitude “Nixon in China,” which might now be the most popularly admired opera by a living composer.