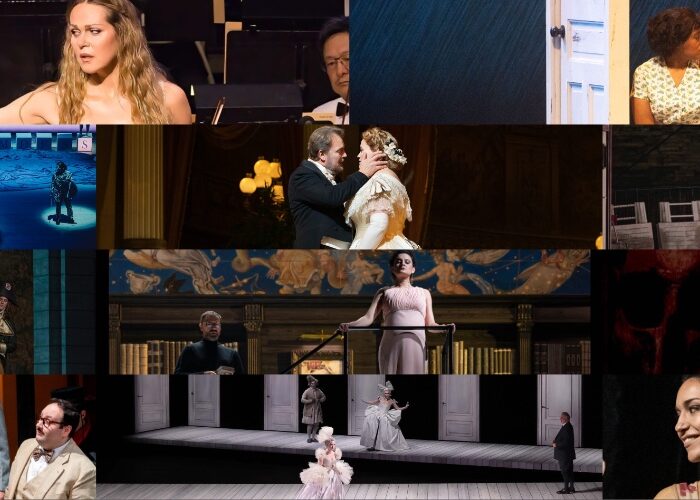

A Stroll Through The Many Genres of Opera (Part One)

By John VandevertOpera is not one thing, as many people know. Instead, opera is an umbrella term for a large host of different categories and types ranging from the typical to the rather peculiar. While Mozart looks one way, Monteverdi and Wagner will look a different way. Of course they all follow the same trajectory, but their style has led them in divergent directions.

If you go onto Wikipedia, you will find a category dedicated to the topic of opera’s many genres, but I want to make things simple. Rather than try and understand ALL the subgenres of opera at one time, it’s helpful to break the task down into large groups. This is Part One of a three-part series that is focused on the different genres of opera, from the 17th century to the present!

Because it is so important that opera is not just carried out onstage, but off it as well, in this post we will take a look at the three general groupings of opera categories, and some examples from each, so you will be in-the-know for your next performance.

If you happen to go to the opera one night, you are bound to stumble upon any one of the five most common types of opera still performed today in opera houses around the world. They are: Opera seria, opera buffa, opera semiseria, opéra comique, and grand opéra. But what are they, and what are some real, onstage examples?

Opera Seria

Developed during the 18th century with the rise of “bel canto” (beautiful singing) and made popular by composers like Antonio Vivaldi, Joseph Haydn, and Giovanni Pergolesi, this style became the predominate method of opera during the first half of the century. The style is recognized through its iconic structure, an exchange of musical movements between recitative and music, often beginning with an overture constructed in the “da-capo” form.

You can often tell that you are watching an opera seria by the “serious” nature of the opera’s subject matter, as well as the nature of the opera’s arias as well. This kind of opera was made to profess a universal ideal, a moralistic tale, an allegory for some type of lesson to be learned and ruminated upon by the audience. Such idealized themes were taken from Greek theatre, with many operas using characters representing gods and virtues. The audience for these operas were generally the courts and nobility, thus the operas were never really for general consumption. By the second half of the 18th century, the opera seria was in relative decline as the antithetical style of “opera buffa” (or Italian comic opera) rivaled the supremacy of the former.

Examples of this style include Christoph Gluck’s “Il Parnaso confuso,” Leonardo Vinci’s “L’Eraclea,” Wolfgang Mozart’s “La clemenza di Tito,” and the well-known “Rinaldo” by George Handel.

Opera Buffa

As opera seria grew alienated from the public, the more accessible style of opera buffa grew in popularity. Meaning “comic opera,” this style is identified by its far more humorous themes and plots, along with faster, more eloquent melody lines, and a characteristic style of sung text between or before arias and scenes called “parlando” (recitative). The style focused on the technical precision of the singer, as well as their ability fully embody the character and be funny with their fellow singers.

At the time, the “castrati” were also being phased out and so virtuosity was steadily becoming the hallmark of a quality operatic artist. A further development included solos, duets, trios, and ensembles; an expansion on the forms allowed in the previous style. With this style, the middle-lower classes of society were now represented on the stage , and often at the expense of the nobility. A routine element of opera buffa were parodies of elite problems and bad rulership. Opera buffa was one of the main reasons that opera became a normalized form of musical entertainment, although by the 19th century and the birth of Romanticism, the style was quickly replaced with other, far more dramatic, forms.

Examples of this style include Giovanni Pergolesi’s “La Serva Padrona,” Niccolò Piccini’s “La buona figliuola,” Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” and Antonio Sacchini’s “La contadina in corte.”

Opera Semiseria

While many of the operas from the latter half of the 18th century qualify as being a blend of the “serious” and the “comic,” it is important to isolate the genre of opera semiseria (“dramma giocoso,” or “joking drama”). While dramma giocoso did, historically-speaking, come first—being developed during the later 18th century by the “Neopolitan School”’ of composers within the area in and surrounding Naples, Italy—opera semiseria found its popularity during the early-mid 19th century, with composers like Gioachino Rossini and Gaetano Donizetti.

Additionally, the greatest non-compositional name to come out of both styles, and the one preceding it, was the Italian librettist Carlo Goldoni. The main difference, however, between the two styles is that while opera semiseria more often leans towards the serious element when speaking of plot but the comic in terms of character and comedic relief, the dramma giocoso instead always ends on a happy, usually joyous, note, with less focus on the ‘relief’ part. It must be said that the differences are few and far between, although the dramma giocoso was more often associated with opera buffa and less with semiseria. Regarding semiseria, it was a Italianized version of ‘Comédie larmoyante’ (also known as ‘melodramma semiserio’).

Examples of these styles include Mozart’s “Cosi Fan Tutte,” Ferdinando Paër’s “Griselda,” Vincenzo Bellini’s “La sonnambula,” and Rossini’s “La Cenerentola.”

Opéra Comique

Lest you think comic opera was confined to Italy, in France the style was developed under its Francophone title of ‘opéra comique.’ Similar in many ways to other French genres of musical entertainment like the comédie en vaudevilles, French comic opera is identified in its usage of French, along with the hallmarks of opera buffa including understandable plots, characters from everyday life, and, most of all, humorous situations with uplifting resolutions. The style inherited much from its former style known as ‘comédie mêlée d’ariettes’ (comedy mixed with little arias), prevalent during the Ancien Regime and made popular by composers like Gluck and Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny.

The ‘Querelle des Bouffons’ (Quarrel of the Comic Actors), that raged from 1752-1754 , was a controversial aesthetic feud that discussed the superiority of either French or Italian comic opera. Ultimately the latter was deemed not ‘suitable’ for French tastes. Nevertheless, a domestic scene emerged and, after a while, the iconic French vaudville style of theatrical entertainment made its way into Italian comic opera, forming what we know as opéra comique. The composer André Grétry is inarguably one of the biggest names of the style, his works incorporating political subject matter and a masterful handling of the French sensibility and Enlightenment themes.

Examples of this style include Monsigny’s “Le déserteur,” François-André Philidor’s “Tom Jones,” Luigi Cherubini’s “Lodoïska,” and Daniel Auber’s “Fra Diavolo.”

Grand Opéra

As the 19th century progressed, and Romanticism began changing the orientation of everything from philosophy and art to politics and beyond—the Counter-Enlightenment movement growing out of this—opera too underwent a shift. As big theatres began sprouting up, and a bourgeoise middle-upper class grew, there was an increased demand for drama and extravagance at the theatre. Gone were the days of solely “working class” spectacles and understandable narratives. In its place, large-scale and potently majestic orchestral scores, elaborate sets, highly ornate costumes, lighting, and plots, accompanied by incredibly melodic, captivating, and memorable vocal histrionics were desired.

Traditionally, grand opéra is considered to have begun in France, where “French Romantic opera” first emerged. Popularized by composers like Rossini, George Bizet, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Gaetano Donizetti, Michael Balfe, Hector Berlioz, Charles Gounod, and Camille Saint-Saëns, grand opéra was about telling huge stories with as much detail as could be afforded both visually, musically, and vocally. The Golden Age of grand opéra came during the middle of the 19th century, during Wagner’s early reformulation of opera. You can recognize operas from this period by the lushness of the musical textures, drama of the costumes and sets, focus on heroic stories, ubiquitous usage of exoticism, and plot points taken from “Oriental” tales and places like the Middle and Far East.

Examples of this style include Meyerbeer’s “Les Huguenots,” Rossini’s “Guillaume Tell,” Gounod’s “Faust,” Bizet’s “The Pearl Fishers,” and Berlioz’s “Les Troyens.”

Categories

Special Features