Opéra National de Paris 2025-26 Review: Carmen

Calixto Bieito’s incongruous ‘Carmen’

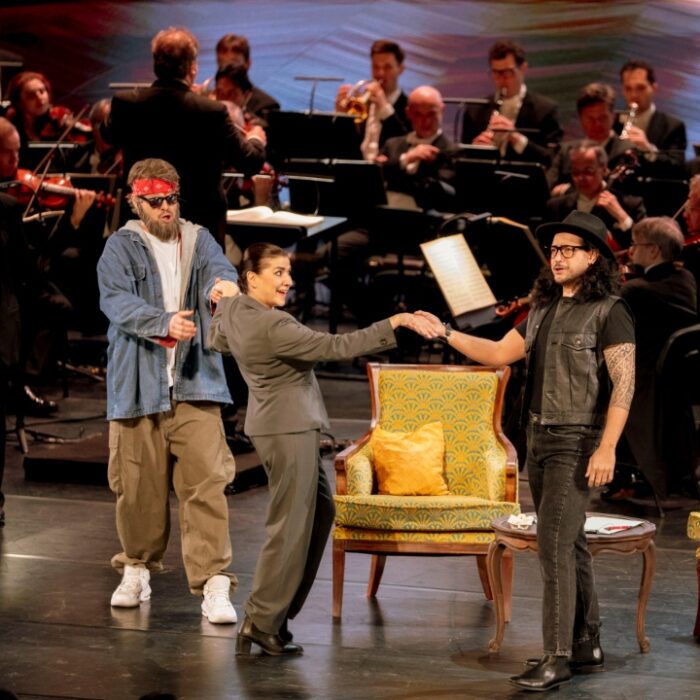

By Ossama el Naggar(Credit: © Benoîte Fanton)

“Carmen” is just about the last opera one would think of as homoerotic, yet this is the vibe of this Paris production; it’s haunted by the male body as object of desire. Other adjectives used to describe it would be bleak, vulgar, obscene, violent and most of all angry. Judging from the costumes, Calixto Bieito’s staging is transposed to the 1970s, the last years of Franco’s regime. As a Spaniard, Bieito’s perception of his own country’s past is understandably quite emotionally charged. Though a critical view of the period is not only justified but also necessary, Bieito’s view is also incoherent. If Franquismo was overtly macho and inherently violent, like other forms of authoritarianism, it was not chaotic. Discipline, religiosity, family “values” and decorum were also among its obvious traits. However, Bieito takes us to a terrifying place, a charmless, violent and chaotic Spain that is highly perilous, especially for women.

A Confusing Production

The opera opens to soldiers (“Sur la place chacun passe, chacun vient, chacun va ; drôles de gens que ces gens-là !”) raising the Spanish flag, while one particularly buff soldier runs in circles in his underpants while valiantly holding his rifle. In Franco’s Spain, this surrealist scene would have led to the soldier’s dismissal and/or imprisonment. The poor man eventually collapses from exhaustion and his limp body is carried off.

When Micaela arrives on the scene to inquire about Don José, the soldiers and officers are like wolves in heat who, contrary to both Spanish chivalry and Franquista official decorum, touch their own crotches, harass and manhandle the country girl. Likewise, when the girls from the cigarette factory take their break, they’re watched by sexually aroused soldiers whose bodies sway in excitement. Barechested, buff military men were more prominent than Carmen herself throughout the first act.

Carmen’s haunt, Lillas Pastia’s tavern, is done away with; Act two simply takes place on the street as Zuniga, officer of the guard and José’s superior, Carmen, Mercedes, Frasquita and their pimps get out of a large Mercedes-Benz, a symbol of wealth among the poor in 1970s Spain. It’s clear from this depressing staging that all three women are prostitutes, which considerably alters the dynamics of the opera. Lillas Pastia, a name heard but not seen in the opera, becomes an actual character and likely the gang leader. He even has a young daughter, and Frasquita is the mother. The child symbolizes innocence and possibly Spain itself. Pastia brings the child garlands of Spanish flags to decorate her tiny Christmas tree; an indication of excessive and conspicuous patriotism. To mock that patriotism. Zuniga’s aide-de-camp uses the Spanish flag to clean the car.

With this attention to political innuendo, Act two’s sequence of events lose their significance. For example, the wonderful aria, “Les tringles des sistres tintaient,” with its ballabile rhythms, is inexplicably performed on the street. Oddly enough, Escamillo, the bullfighter, happens to be there too, when he encounters Carmen and company.

Unfortunately, this production did not use Guiraud’s sung recitatives, but rather the more frequently used spoken dialogues, though the latter were considerably cut, to the extent that certain aspects of the story were unnecessarily confounding. Case in point, Escamillo leaves a scene without his delicious exchange with Carmen, in which she flirtatiously says “Il est permis d’attendre, il est doux d’espérer.“ Thus, the development of his tryst with Carmen was more a mystery. As for the marvelous quintet “Nous avons en tête une affaire” in which the contraband mission is proposed, it’s implausibly sung in a public place without any fear of authorities (in a Fascist country!).

Act three, which normally takes place in the mountains, was transposed to a car park, a perilous meeting place for bandits in a tightly-controlled Fascist country. Oddly enough, the parking lot in question looked like that of the corrida, home of the bullfight, which takes place in the last act. How else can one explain the huge effigy of a bull at the gate?

The final act had no sets, just a circle alluding to where Escamillo will butcher the bull – or is it where José will murder Carmen? At the opening of Act four, there are no ambulating salespeople singing “A deux cuartos ! A deux cuartos !;” spectators take their place. With nonexistent sets, all attention is on Carmen and Don José, an audacious and ill-advised decision (to be soon clarified).

A Mixed Cast

Though most of the singers were excellent, the singing does not save the production, namely because the title role is gravely miscast. French mezzo Stéphanie d’Oustrac is a decent actress, but her voice is too light for the role, especially for the 2745-seat Opéra Bastille. D’Oustrac, who started her career in baroque roles, has a lovely way of enunciating, likely thanks to her career in early music. However, she tries to compensate for her small voice and light timbre by artificially darkening her voice, which can be grating. Dramatically, she portrays Carmen as self‑confident. In her first appearance, from a telephone box, she utters the words of the famous Act one “habanera,” “Quand je vous aimerai ? Ma foi, je ne sais pas,” addressed to her interlocutor on the phone. Original, but incoherent as it is, her answer to the male chorus’ “sois gentille, au moins réponds-nous et dis-nous quel jour tu nous aimeras!” At least she doesn’t seem like a man-eating monster, and as such it’s credible (at least in Act one) that the country boy Don José could fall for her. Act two’s “Les tringles des sistres tintaient,” executed as an odd street dance, is amusing but D’Oustrac’s polished voice doesn’t do it justice. Likewise, the card trio was sadly far from solemn, a missed opportunity by all, but especially the conductor. This is one scene where Carmen needs her low notes – absent in d’Oustrac’s case.

American tenor Russell Thomas had the least perfect diction among the cast, but his enunciation in the arias and duets was more than adequate. Despite singing heavier roles in recent seasons, his lyric tenor is still brilliant and has all the heft needed for this dramatic role, and none of the baritonal quality favored by many past Don Josés. His Flower Song, “La fleur que tu m’avais jetée,” was moving as well as technically flawless. But the aria’s emblematic final dimenuendo was eschewed. While upholding his virility, Thomas managed to show his tenderness in his phrasing of “O Carmen, oui, te revoir!,” “j’étais une chose à toi” and “Carmen, je t’aime.” He convinced as a gauche provincial Navarro. In the final scene, both Russell and d’Oustrac underplayed the tension, which is preferable to overplaying. Given the French mezzo’s “cool” portrayal and modest vocal means, the confrontation was rather underwhelming. One expected more passion at this stage. Nonetheless, Thomas’ performance, both acting and singing, was dramatically convincing.

Egyptian-born New Zealander Amina Edris was a lovely Micaëla, an often dull role, especially when juxtaposed with the overwhelming Carmen. Bizet’s assignment of overly serene music to Micaëla makes her so angelic that she has no chance against the sultry Carmen. In many productions, a tepid Micaëla seems most appropriately destined to become a nun. Not so in the case of this young soprano. Edris’s Micaëla was no shrinking violet. She’s serious and reserved, but also determined to get her sweetheart. Facing the soldiers in Act one and the bandits in Act three, she handily stands her ground. Thanks to her beautiful phrasing, ease in the upper register and natural acting, this was one charming country girl. She exuded joy in her Act one duet with Don José, “Parle‑moi de ma mère,” and in Act three’s “Je dis que rien ne m’épouvante,” she was luminous and moving.

Escamillo, despite the brevity of the role, is not an easy one, as it requires both high and low notes. It is truly a bass‑baritone role, and few baritones have ease in the lower part of the role. Uruguayan bass-baritone Erwin Schmitt did not disappoint. Though he wore no impressive toreador uniform in his initial appearance in Act two, his was an effective Escamillo, exuding virility and reaching his aria’s lower notes effortlessly. Escamillo’s Toreador Song, “Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre,” which was well interpreted with excellent diction, elicited even more applause than Carmen’s “habanera,” and rightly so.

Conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson was adequate in steering much of the opera in the right direction. Given d’Oustrac’s limited vocal means, one would have hoped for softer playing during the mezzo’s arias and scenes. Act two’s quintet “Nous avons en tête une affaire,” a brilliant avant-garde piece with modernist syncopation, was performed as an afterthought, with no sizzle or even humor.

A valid question to ask regarding Bieito’s highly-controlled Spain: What is the likelihood that a “good” country boy from Navarra – a designation bestowed on José by the librettists – would break his commitment to his fatherland, to the army in which he serves, to his mother and to his sweet innocent fiancée? Would he really throw it all away for a gypsy woman from Andalusia who survives from contraband and petty criminality? The answer is clearly no! Bieito is mistaking authoritarian regimes for revolutionary ones, where established systems have already collapsed and society is in turmoil. His imaginary Spain never existed; he’s merely channeled everything negative into his setting of choice. Consequently, as the characters and setting aren’t credible, nor is the likelihood we will be moved by the story.