CD Review: Dominick Argento’s ‘The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe’

By Bob DieschburgIf ever as crepuscular an author as Edgar Allan Poe were seasonally appropriate, November—or certainly around Halloween—would be the time.

Shrouded in mystery, his life (and death) echoes the tragedy of “Ligeia” (1838), “The Black Cat” (1843), and “Annabel Lee” (1849). That is just to name a random few which, a literary legacy, have stood the test of time.

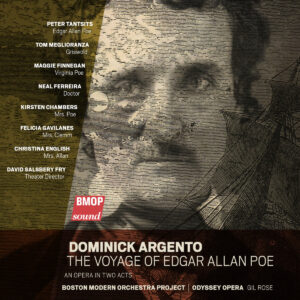

Fittingly, then, BMOP/sound (the label of the Boston Modern Orchestra Project) capitalizes on Poe’s eeriness with the release of composer Dominick Argento’s eighth—and arguably maturest—opera: “The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe.”

Premiered in 1976, it has variously been ranked among the finest American operas–at least as far as contemporary repertoire goes. Yet the amounts of praise starkly contrast with “Poe’s” relative scarcity on playbills. And herein lies its limitation: Argento’s opera is very much a child of its time–slightly rebellious, and steeped into a tonal-atonal blend of post-War modernism.

It layers elements from grand opera, notably the choral tableaux, with expressionistic, if not outright theatrical psychologism. There are echoes of Debussy and early Berg, particularly in the fluid timbres of the dream and sea imagery. Poe’s voyage runs parallel to his mental disintegration.

Yet for all its theatricality and–at times–cinematic logic, the narrative might feel overly deictic–frustratingly so. Charles Nolte’s libretto often foregrounds the act of signifying itself–through post-expressionist gesture which may come across as heavy-handed.

A psychoanalyst’s delight, “The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe” relies on symbols, such as the omnipresent Rufus Griswold, his real-life detractor who moves, in the opera, from representing the external world of moral censure to becoming the prosecutor of Poe’s soul.

Indeed, the second half of “Poe” is a judgment scene, in which Griswold—as Poe’s shadow self—embodies the opera’s central fear that artistic genius might be inseparable from moral decay. Tragedy in Poe’s life is, so to speak, self-inflicted through the crassness of his literary works. Virginia (his dead wife) and other spectral figures appear at this phantasmagorical hearing, which—in essence—carries frighteningly totalitarian undertones.

It remains up to debate whether the listener is to take the opera’s message at face value—or, by implication, whether Argento believes in the Romantic myth of the poète maudit or not.

BMOP—in partnership with Gil Rose’s Odyssey Opera—delivers a tight reading of the score.

It foregrounds orchestral color which, in time, adopts a cinematographic profile. This is especially true of the barcarolle-like figures in the lower strings, which significantly contribute to the opera’s haunting, maritime imagery.

Rose emphasizes atmosphere over text-heaviness. His approach is integral to the music, and dissonant parts like the death hallucinations of Virginia represent no more of a rupture than necessary.

Purists might think the opera’s postmodern aesthetic was compromised; but whether that would have held up, half a century later, is an entirely different question. Rose did well not to take a gamble—and to let BMOP’s release be without any pretensions.

For the characters, he relies on an all-American roster led by tenor Peter Tantsits as a subtle and tortured Poe. He very artfully strikes a balance between bel canto linearity and speech-inflected declamation—consistent with the requirements of Argento’s vocal writing. As such, the role eschews showpiece arias in favor of smaller-scale vignettes built around Poe’s fragile state of mind.

No doubt, Tantsits fully identifies with his literary counterpart, though his metallic timbre might, for better or for worse, appear to overstate Poe’s agony.

Tom Meglioranza is a superb Griswold, whose clear diction allows for a multilayered interpretation in line with the role’s semiotic ambiguity. Maggie Finnegan lends her ethereal soprano to the part of Virginia Clemm.

The secondary roles of Mrs. Poe and Mrs. Allan are skillfully fleshed out by Kirsten Chambers and Christina English respectively—as are a host of tertiary parts, as well as the chorus, a quasi-character of its own.

“The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe,” then, is in more than capable hands, and its reception by the listener might depend more on inherent strengths and limitations than on the overall quality of the BMOP release.

As it is, the opera is some kind of hybrid: grand expressionistic theatre—at a key juncture in American musical history.