Wiener Staatsoper 2019-20 Review: La Traviata

Ekaterina Siurina Saves The Day In A Heroic Turn As Violetta

By Francisco Salazar(Credit: Wiener Staatsoper/Michael Pohn)

The Wiener Staatsoper’s opening night of the 2019-20 season got off to an interesting start.

The season was set to open with a revival of Jean-Francois Sivadier’s production starring Irina Lungu in the title role. But drama struck 20 minutes before the presentation when Lungu canceled.

Luckily Ekaterina Siurina, Charles Castronovo’s wife was in the house and had sung the production last season when she made her role debut. But with no rehearsal time or prep time, Vienna State Opera General Director Dominque Meyer was forced to delay the performance 20 minutes to adapt the costumes and allow Siurina time to warm up. The General director walked out on stage to announce the dramatic situation to the public and when Siruina walked out on stage for her first appearance, the soprano was lauded with a huge ovation.

A Heroic But Mixed Turn

So, with so little time to prep and having to step in for opening night, how did Siurina perform? The question is a bit difficult to answer as the performance was a mixed bag.

Vocally Siurina has a charming and bright middle voice that projects well into the Wiener Staatsoper but can sometimes run thin in large ensembles, including the second act concertato where she was covered by the large ensemble.

However, her upper register is strident and lacks flexibility. In her first act Siurina, who most likely nervous, had a difficult time adjusting to the conductor and in her double aria “E Strano” and “Sempre Libera,” the soprano tended to go off-key and run out of breath. She would always fall behind the conductor particularly in the latter piece. In “Sempre Libera,” which rises to a C#, the soprano lacked clarity in intonation and pushed every ascending line, making for an unpleasant sound. Siurina also tended to make slight pauses during the lines “Sempre lieta ne’ ritrovi,” which made for an awkward interpretation that lacked energy and cut the vibrancy out of Verdi’s music.

The soprano improved in the second act but her diction and opening lines of the duet with Germont lacked warmth and depth and it seemed that whatever she was doing dramatically was disconnected from her vocal line.

It wasn’t until the “Dite a la Giovane” that Siurina’s voice warmed up and it found a dramatic coloring that really connected with her acting. Here she sang with a tender pianissimo that connected her line with such grace and sorrow and one felt the heartbreak that Siurina’s Violetta was dealing with. The emotion continued to crescendo in the lines “Morro! la mia memoria” where Siurina finally unleashed her full voluminous potential and gave her voice a raw and dramatic resonance. Then her “Amami Alfredo” displayed even more intensity as she rose to her top with ease, even if with a bit of harshness.

Unfortunately, the second half of Act two fell short vocally as she was underpowered in the ensembles and the beginning of the third particularly her “Addio del Passato” lacked any dramatic potency. While it was sung with elegance and beauty, it felt as if the soprano was just getting into the piece as she sang her final lines. There was no indication of Violetta’s suffering or pain, and the decision to cut the second verse also limited her opportunity to develop her interpretation further.

Her best singing came in the final duet and finale. “Parigi O Caro,” sung with tenor Charles Castronovo, featured ardent chemistry as every phrase lined up perfectly, even as the orchestra fell behind. The voices melded beautifully, creating a tender moment as they looked and held each other. And then in the “Ma se tornando non m’hai salvato, A niuno in terra salvarmi è dato,” Siurina began the phrase with a whisper that crescendoed to a fortissimo and expressed the final two words in a haunting manner. Her crescendo into the “Ah!” was also a virtuosic and dramatic coup as she smoothly went into the “Gran Dio! morir sì giovane” descrescendoing with ease. The trills in these lines were messy but they added to Siurina’s interpretation and gave that sense of a woman struggling to live.

Then in the ensemble “Prendi, quest’è l’immagine,” Siurina cut short the phrases as if her Violetta lacked breath. It was mesmerizing as she created a delicate timbre that regained strength in her final lines “E Strano” which she emoted with clarity and vibrancy. The “Oh! Gioia” was sung with the same vitality that her voice attempted to give in the first act.

Dramatically and physically, Suirina was much better at giving her Violetta a clear arc. At the beginning of the opera one could see Siurina’s Violetta in taking medicine and praying for her health to improve. Then when the curtain unveiled the party, this Violetta became a coquette and flirt as she attempted to charm Alfredo by making him jealous of the Barone. Instead of receiving Alfredo’s flowers, she took the baron’s and then picked one out and gave it to Alfredo.

During their duet, it was like a cat-mouse game as Alfredo attempted to seduce her to no avail. In her “Sempre Libera,” Siurina’s Violetta attempted to fight back Alfredo’s call, taking any liquor she found. But in the end, she fell for her him and in the final image of the first act, Violetta fell into Alfredo’s arms.

In the second act, Siurina’s Violetta returned to seducing Alfredo, taking off his tie and unbuttoning his shirt. But this time the movements were filled with tenderness and as she sat on the floor, her look was filled with love as they kissed.

The devastating moments in the duet with Germont was a battle of wills where Siurina defied Thomas Hampson’s Germont, throwing her chair and walking away as she grabbed hold of Alfredo’s jacket. But as she saw her impending loss, this Violetta threw herself to the floor and showed a weak and vulnerable side. That vulnerability was more evident as she embraced Castronovo’s Alfredo during her “Amami Alfredo” and would not let go.

Her final act was the dramatic tour de force as Siurina embraced a delirious side to Violetta who first walked on stage in her dress, only to take it off and walk about directionless as if attempting to embrace her old self. Then as she embraced Castronovo during the final duet and ensemble, Siurina looked at her Alfredo as if she did not want to let go, kissing him and embracing him with desperation. In her final moments Siurina walked toward each person, attempting to remain standing for as long as she could. She eventually succumbed to hr fate in the final seconds, only making that march to death all the more poignant and shattering.

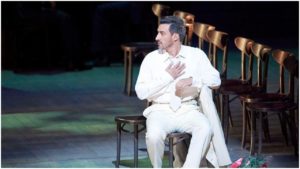

An Ardent Tenor

In the role of Alfredo, Charles Castronovo brought an impassioned tone that he carried throughout the evening.

Castronovo first appeared as a shy young man in pursuit of Violetta, who gained strength as she flirted with him; in the “Brindisi,” he took her by the arms and started dancing. Then in the first act duet “Un di felice, eterea” Castronovo approached Siurina’s Violetta, passionately singing with an elegant timbre that connected each phrase beautifully as he swayed from a piano and crescendoed into a forte with ease. His vocal dynamics were so effortless as he moved about the stage, flirting and finally kissing her at the end of the duet.

At the start of the second act, Castronovo sang his aria “De miei bollenti spiriti” with fervor and sensuality that was highlighted by his joyful facial expressions and his quick movements to take off his shirt and join Violetta in bed. But that joy quickly turned to an uncontrolled Alfredo in his cabaletta as he sang with ferocious energy and tone that resonated throughout the auditorium.

This Alfredo’s agitated spirit was even more present during Violetta and Alfredo’s encounter in Flora’s party where he arrived drunk and wildly moved about the stage. During “Ogni suo aver tal femmina,” Castronovo’s voice shifted away from the elegance in the first scene. His accented notes and emphasis on the consonants were highlighted by his brashness on stage as he pursued and cornered Violetta. That crescendoed into Castronovo emoting the final “che qui pagato io l’ho” with a violent tone that was further emphasized by his violent energy as he threw money at Violetta. He repeated the action until Hampson’s Germont slapped him, weakening him and bringing Castronovo’s Alfredo’s to the floor.

In the third act, Castronovo returned with a passionate tone, singing the aforementioned “Parigi o caro” with tenderness and connected beauty. His voice displayed flexibility as he held Suirina in his arms. The chemistry between the two ignited in these moments as their voices came together with little effort, reflecting tender and passionate fire in the duet. But one could sense desperation in Castronovo’s Alfredo during the duet and that desperate tone only grew in the ensemble during the phrases “No, non morrai, non dirmelo;” here, he poured out all his emotions and would not let go of Violetta, embracing her one last time with tremendous intensity.

Credits: Wiener Staatsoper / Michael Pöhn

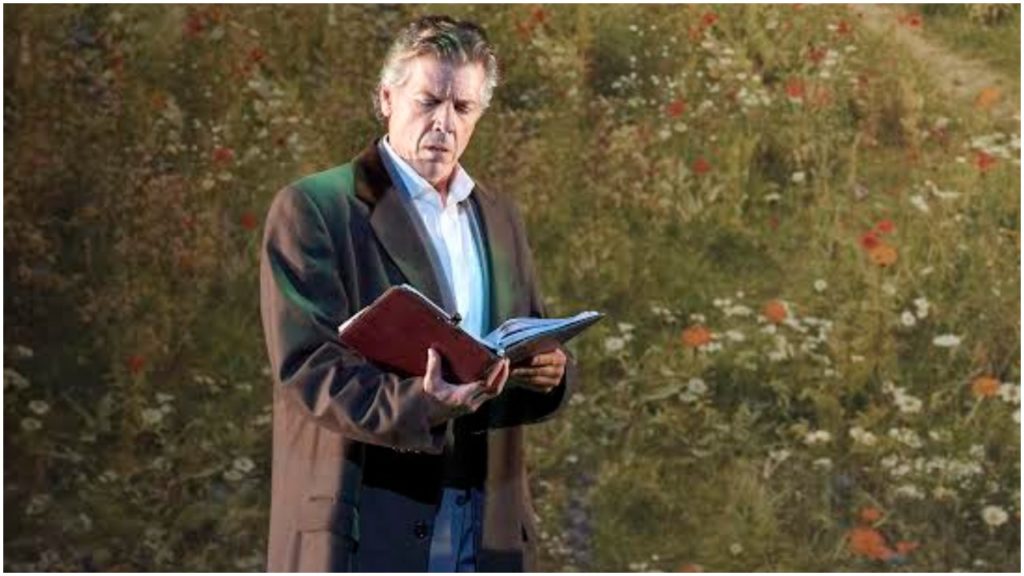

A Veteran Baritone

In the role of Germont, Thomas Hampson brought his signature interpretation back to Vienna. The baritone, now in his mid-60s, continues to show resonance and an imposing voice. His timbre now has some coarseness that while difficult to warm up to, is very effective, especially in the staccato lines. Hampson is also a master with text, every word delivered with great clarity.

In the role of Germont, Hampson began his portrayal with imposing opening lines that rang freely through the auditorium. As he stepped onto the stage his stance towards Siurina’s Violetta was demeaning, bringing his authority to the scene. But as the duet developed, that imposing quality and vocal power softened. While the flowing legato lines were sometimes cut short and had crudeness, the baritone used this to show a weakness in Germont. That weakness soon turned to tenderness in his lines “Piangi,” which he phrased to feel like a gentle weep. Here Hampson picked up Siurina with the grace of a loving father. This particular action featured a gorgeous arc, with Hampson’s Germont initially unsure of how to respond to Violetta’s embrace before fully supporting her and giving himself over to her emotionally.

During “Di provenza,” Hampson came into the scene with happiness at seeing his son. He sang with an ardent and bright tone, connecting each phrase and attempting to win over his son. Hampson’s face radiated warmth and a smile as he sang each both verses.

But that quickly turned as Castronovo’s Alfredo wouldn’t accept his father’s embrace with Hampson taking Castronovo’s Alfredo by the shoulders and shaking him violently. However, as he saw his mistake, Hampson backed off and during his cabaletta, the baritone looked toward Castronovo with hesitance. The vocal line was detached and breathy, emphasizing the hesitance and repentance; the coloratura florids were sung with clarity and rapid textures.

That violence that Germont hinted at in the scene with Alfredo came to fruition during Germont’s “Di Sprezzo degno” as Hampson slapped Castronovo and emphasized the consonants on each line. He gave the lines a mix of anger, repentance, and vulnerability, which added to the dimension of this character. And as he sang the concertato, Hampson looked toward Siurina’s hurting Violetta and then at Castronovo’s physically weakened Alfredo, his character fighting differing emotions to great dramatic effect.

Credits: Wiener Staatsoper / Michael Pöhn

An Uneven Leader

In the pit, Giampaolo Bisanti had an uneven night with the orchestra. While he tended to give Verdi’s music swift tempi, such as in the gambling scene of Act two and in the Brindisi,” the conductor had mannerisms that tended to underwhelm Verdi’s music. For example, in the cabalettas such as Alfredo’s “O Mio rimorso,” he would make sudden decrescendos that slowed the flow of the music. Then there were numerous accents that exaggerated such moments as when Germont enters the stage or in Alfredo’s “Ogni suo aver tal femmina.”

The violin solos in the Act three prelude and in Act one were also a bit messy with a legato line detached and lacking the elegance of Verdi’s music. However, that did improve in the final “E Strano” in Act three. In many ways, there was a wonderful juxtaposition between Siurina’s detached phrasing and the violinist’s more connected line that allowed the scene even more poignancy.

A Modern Take

Before I conclude this review one has to take note of Sivadier’s modern production which respects and updates the work in a minimalist staging full of black and blue.

One interesting element in Sivadier’s staging is how he separates Violetta’s private from her public figure. At the start of the opera, he pulls a blue curtain that separates Violetta from the full stage. Here she is seen praying and taking medicine from Dr. Grenvil and then that is repeated at the start of the third act where she is alone sitting on a chair and being helped by Annina as she takes off her makeup and her dress. This element allows audiences to see a clearer look at the private Violetta that is separate and different from the party girl that she appears as elsewhere.

The dress, which is reminiscent of the one in the famed Willy Decker production, is also an element that Sivadier uses to represent the private vs. the public. When she is in parties does she wear the complete blue and black outfit, but when she is in private or with Alfredo, she strips down to a slip to show her inner feelings and emotions. The dress, in many ways is a symbol of the old life she is attempting to break free of.

Sivadier’s vision is clean but raw on some occasions, particularly in Violetta and Germot’s duet or in the final act where Violetta is delirious. The singers are forced to bring all their acting abilities in order to create a vivid picture of the suffering these characters go through. In particular, the third act is a physical challenge for Violetta as she must sing, walk and run throughout the stage, almost as if she was in a mad scene.

Props must go to the ballet choreographed by Boris Nebya in which he was able to adapt the toreadors into dancers chasing after Flora and attempting to seduce her. In many ways, that was a bullfight in and of itself and the movements were well-timed with the music.

But there are elements in the production that sometimes feel a bit forced, like the photograph at the end of the first act party. Before the choristers leave, a photographer lined everyone up on stage to take a photograph that was never revealed or simply brought back.

The spotlight during “Sempre Libera” was also an issue as it took away the rawness of the production and simply felt gimmicky. Instead of isolating Violetta as was probably the intention, Violetta felt more like a showgirl.

Nevertheless, this was a “La Traviata” with lots of backstage drama that resulted in a solid and memorable performance.