Theater Basel 2025-26 Review: El Barberillo de Lavapies

Christof Loy’s Zarzuela in Switzerland Is a Rare Treat

By Zenaida des Aubris(Credit: Cingo Hoehn)

Finding a performance of a Zarzuela in Spain is rare enough, but in Switzerland? And put on by a German stage director? Definitely in the category of rare occurrences! It so happens that the Zarzuela genre is Christof Loy’s special passion and he is doing all he can to introduce new audiences to this unique Spanish blend of theatre, comedy, music and drama. Is Zarzuela operetta, Singspiel, opéra comique or musical theatre? In truth, it is a combination of all of these—yet with its own unmistakable identity. Full of fast paced patter, dance, brilliant musical numbers, humor, historical references, satire, its performance history goes back to the 17th century, with a strong revival of interest in the late 19th century.

Zarzuela belongs to the Spanish DNA as much as the musical belongs to the American heritage. There are literally thousands of compositions by hundreds of composers. Loy chose one of the masterpieces of this genre, “El barberillo de Lavapiés” by Francisco Asenjo Barbieri (1823–1894), a leading figure of 19th-century Spanish musical theatre and a founder of the modern zarzuela. Premiered in 1874 in Madrid, it’s one of the finest examples of the three-act-style or género grande–yet politically tinged and full of lively local color.

Set in 18th-century Madrid during the reign of Charles III, the story follows Lamparilla, a witty and patriotic barber from the working-class Lavapiés district, and Paloma, a spirited seamstress and Lamparilla’s love. Beneath the comic surface of street gossip and romantic intrigue lies a subplot of political conspiracy: the noblewoman Countess Estrella and her lover Don Luis are entangled in a plot to overthrow the corrupt minister Grimaldi. With cunning and courage, Lamparilla and Paloma help them escape the authorities, embodying the sharp intelligence and vitality of the common people. The work ends in a jubilant street celebration—justice restored, love affirmed, and laughter prevailing.

The work mixes romance, satire, and local color, celebrating the cleverness and vitality of ordinary persons, while gently mocking the pretensions of the ruling class. It ends with justice and good humor prevailing amid festive street scenes in a grand-finale song-and-dance happy end.

Production Details

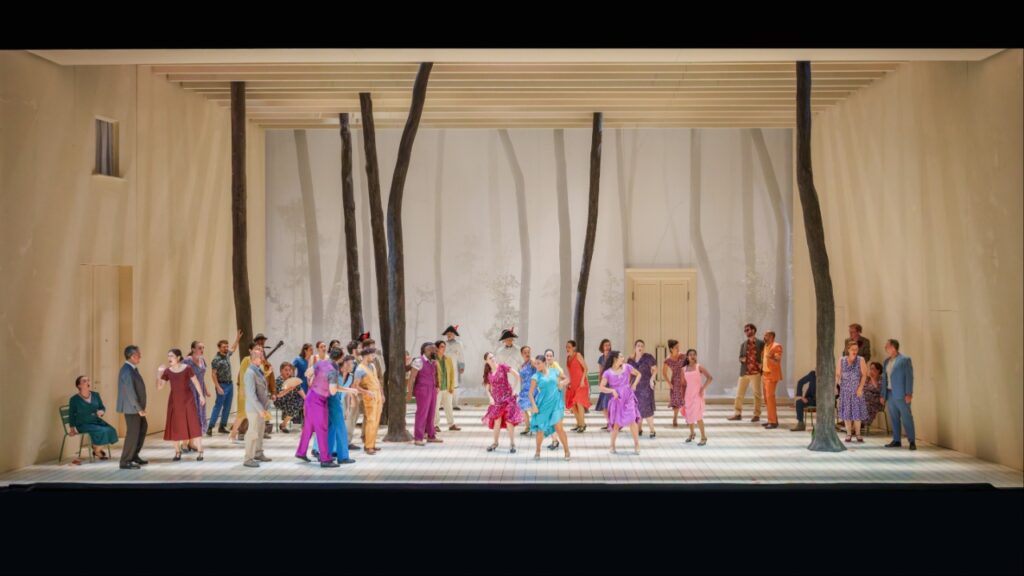

Christof Loy and his set designer Manuel la Casta place the action in a timeless white space, subtly referencing the historic riots that erupted in Madrid when street lighting was first introduced—many citizens feared it would make it easier for police to track suspects–with overturned street lamps in the first act alluding to these events. Robby Duiveman designs modern day costumes that reflect the change of the characters from their humble origin to a more exalted class of the course of the acts. Valerio Tiberi tries to convey the glare of Mediterranean sun by turning up the dimmers and delivering very flat illumination, thus sacrificing contrast for any sense of drama whatsoever. Javier Perez blends his choreography of the eight dancers with the large chorus and extras, making for fast moving and intricately paced crowd scenes.

Musical Highlights

The ensemble consisted of native Spanish speaking singers, lending authenticity to the rapid-fire dialogue (with surtitles in German and English). Baritone David Oller embodied Lamparilla as a close cousin to Mozart’s or Rossini’s “Figaro”–street smart, patriotic, witty and very much in love with his leading lady. Together with mezzo Carmen Artaza as Paloma, they made a most suited couple, creating their own vocal and musical synergy culminating in a duet so charming it earned an immediate encore, in true zarzuela fashion. By contrast, their aristocratic counterparts seemed pallid. Soprano Cristina Toledo as Countess Estrella and tenor Santiago Sánchez as Don Luis, did their best to bring warmth to roles that Barbieri himself treats with ironic detachment and reveals his clear sympathy for the common folk.

Musically, the work is a blend of popular Madrid street songs, dance rhythms, and elegant orchestral writing. Barbieri elevates the zarzuela grande to an art form comparable to French opéra-comique, combining sparkling ensembles, vivid character pieces, and finely crafted finales. The score captures the flavor of everyday Madrid—seguidillas, fandangos, and jotas mingle naturally with lyrical arias and ensembles of operatic polish. The Theater Basel brought in the musical director of the Teatro de la Zarzuela Madrid, José Miguel Pérez-Sierra, as a leading expert. In comparison to the sometimes furious pace on stage, Peréz-Sierra seemed to lack the ability to communicate the corresponding dynamic fire to the orchestra.

Beyond its wit and charm, “El barberillo de Lavapiés” also reflects Barbieri’s civic pride and liberal ideals. By giving center stage to humble, resourceful characters like Lamparilla and Paloma, he turned the zarzuela into a mirror of Spanish identity—clever, ironic, and deeply human.

As an introductory touch, Christof Loy asked tenor Santiago Sánchez to give a short pre-show talk on traditional zarzuela audience behavior—encouraging spontaneous applause, vocal interjections, and lively interaction. The Basel public enthusiastically obliged, culminating in standing ovations.

May this joyful evening mark the beginning of a Zarzuela renaissance north of the Pyrenees!